Arm and Hand Pain on the Job Site

A doctor's take on wrist, elbow and shoulder troubles common to builders.

Synopsis: Those suffering from tennis elbow, shoulder aches, or carpal tunnel syndrome may be interested in this list of recommendations for pre-work stretching and other ways of generally taking better care of themselves.

A few months back, Andrew Hargrove built a small addition without the benefit of his nail gun. After several days of nailing off sheathing, he came into my office. “Doc, my hands have been killing me. When it started a few weeks ago, it would come and go, but now it’s constant. My hands are numb and tingly and wake me up in the middle of the night.” A drywaller named Ed Johnson had similar complaints and also noted that he had trouble holding on to his tools.

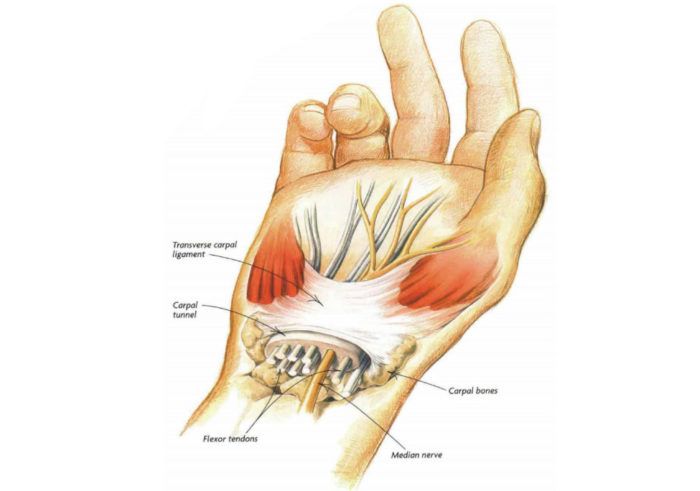

These signs are classic symptoms of carpal-tunnel syndrome (CTS). What is CTS? The carpal tunnel runs through the wrist, bound by bones on three sides and by a heavy, unyielding ligament on the fourth. The flexor tendons, which move the fingers, and the median nerve run through this tunnel. Repetitive gripping and grasping — such as hand-nailing, holding a framing nailer all day, mixing mortar by hand or cutting endless rafter tails — lead to tendinitis, irritation and swelling of the flexor tendons. There is no extra room for swollen tendons in the carpal tunnel. These swollen tendons press on the median nerve, causing the pain, numbness and loss of gripping strength that spell CTS.

Wrist anatomy

The carpal tunnel contains the flexor tendons and the median nerve. With bone on three sides and a heavy ligament on the other, there is no room to accommodate swelling. Repetitive motions, particularly tight grasping, can cause tendinitis, or inflammation, of the flexor tendons. Their swelling pinches the median nerve, causing numbness or pain in the hand and a loss of grip strength, which are symptoms of carpal-tunnel syndrome.

Avoiding repetitive tasks can help to sidestep CTS

Working with your wrist in a neutral position can help you to avoid CTS. As a practical matter, however, this posture may not always be possible for people working in the building trades.

If you can’t always keep your wrist in a neutral position, at least switch tasks, substitute hands or change wrist position to allow different muscle groups to rest. Take frequent stretching breaks.

Wrist neutral is the best working position.

Wrist neutral is the best working position. Flexing the wrist either up or down while working increases the likelihood of developing carpal-tunnel syndrome.

Flexing the wrist either up or down while working increases the likelihood of developing carpal-tunnel syndrome.

Stretches that can help

While the hot water relaxes your muscles during your morning shower, take five minutes to do these stretches. You might feel like you’re doing the macarena, but ten reps of these stretches done several times a day can reduce the chance of developing CTS, and may offer relief if CTS symptoms are present. These stretches also may relieve tennis elbow.

1. Extend your hands as if you were doing a push-up, and hold for five seconds.

2. Straighten your wrists, and relax your fingers.

3. Close your hands into tight fists.

4. Bend your wrists down for five seconds.

5. Repeat Step 2 for another five seconds. Then drop your hands and shake them loosely.

Wearing a splint at night can relieve CTS symptoms. Splints keep the wrist straight to maximize the space in the carpal tunnel, reducing pressure on the median nerve.

Wearing a splint at night can relieve CTS symptoms. Splints keep the wrist straight to maximize the space in the carpal tunnel, reducing pressure on the median nerve.

If you start to develop CTS symptoms anyway, common-sense measures can keep them from worsening. Listen to your body. Modify your work, cut back your hours, and slow your pace. Cutting back on your activity is the most important measure you can employ. Working through the pain will only make it worse. Rest and time allow swelling and pressure on the nerve to decrease.

Wearing a wrist splint at night can be beneficial. The best type has a metal shank that keeps your wrist straight. This straight position maximizes the volume of the carpal tunnel, thereby minimizing the pressure on the median nerve and the flexor tendons. Keeping your wrist straight while you sleep gives swollen tendons a chance to rest. You can find these splints at any sporting-goods store.

Over-the-counter anti-inflammatories (ibuprofen, Aleve) can reduce the swelling of the tendons that run through the carpal tunnel. Cutting down on your salt intake is also helpful. Salt makes your body retain water, which can cause additional pressure on the median nerve.

If these measures don’t improve your wrist in a week or so, or if the initial onset of pain is too bad, see the doctor.

Back to Andrew and Ed

Following the suggestions outlined above, Ed improved and was back to full duty in several weeks. Andrew continued to have problems, so I ordered a nerve-conduction test to confirm the diagnosis. This test is usually done by a neurologist, who sticks needles into the forearm and records the results of small electrical stimuli. Does the median nerve conduct this electricity across the wrist as it should, or is the stimulus slowed? The degree of slowing indicates the severity of the CTS. Based on my confirmed diagnosis, I injected the carpal tunnel with an anti-inflammatory to relieve the swollen tendons and nerve. Several weeks later, Andrew returned to work.

These conservative measures — rest and anti-inflammatory medications, a splint, a low-salt diet and an injected anti-inflammatory — didn’t help Jerry, a cement finisher. Surgery was indicated, so I performed a surgical procedure called a carpal-tunnel release. This procedure divides the transverse ligament, which forms the base of the carpal tunnel, to decompress the nerve. Carpal-tunnel releases are normally an outpatient procedure, and they are over 90% successful in permanently relieving CTS symptoms. Jerry was out of work for a week, followed by three weeks of light duty. Four to six weeks is the usual time frame for getting back to work after a carpal-tunnel release.

Tennis elbow isn’t just for tennis players

“My elbow hurts too much even to hold a cup of coffee,” Bill Schneider told me. “The pain radiates down toward my hand, and I can’t hold on to my tools.” Bill had just started in the trades and was constantly carrying lumber and nailing subflooring and roofing.

Bill had tennis elbow, or lateral epicondylitis. This common complaint is caused by overuse, specifically repetitive gripping. Hammering is probably the most frequent culprit, although I’ve seen many painters with the same problem. Tightly gripping, particularly with your arms extended, puts a tremendous load on the extensor muscles in your forearm. These muscles converge and attach to the bone on the outside of your elbow at the lateral epicondyle. Inflammation of the tendons that attach the extensor muscles to the lateral epicondyle gives rise to tennis elbow.

Elbow anatomy

Tennis elbow is inflammation of the tendon attaching the extensor muscles to the elbow. The extensor muscles in the forearm control the movement of the hand and wrist. They connect to the hand with tendons and can exert tremendous gripping force. While they connect to the hand in several places, many of them attach to the single point of the lateral epicondyle. That’s why too much strenuous gripping with your hands can make your elbow hurt.

Worn at work, elbow braces can relieve tennis-elbow pain. Look for a wide brace or one with a pad over the lateral epicondyle, as shown.

Worn at work, elbow braces can relieve tennis-elbow pain. Look for a wide brace or one with a pad over the lateral epicondyle, as shown.

If you catch tennis elbow before it becomes chronic, you can do a lot at home to improve your condition. As with CTS, gentle stretching exercises in the morning are helpful. I recommend doing them after loosening the muscles for 10 to 15 minutes in a hot shower. A moist heating pad in the evening may also help.

There are several elbow sleeves on the market designed to help tennis elbow. Most patients find them gratifying and end up wearing them all day. Avoid working with your arms outstretched, away from your body, which puts more of a load on these muscles.

If you’ve tried the above and are still having problems, you need to see your doctor. He can prescribe or inject anti-inflammatories, or send you to physical therapy. Tennis elbow virtually never requires surgery. However, it frequently takes four to six months to go away completely.

Working overhead is hard on the shoulders

Scott started losing sleep “because of pain in my shoulder. Now it’s constant, and it even hurts to lift my arm without any load. I can’t work.” A carpenter, Scott had lately been doing a lot of overhead work, hanging drywall, fascias and soffits. These activities are all killers on shoulders. As with elbows, it’s important to get the work as close to you as possible.

Scott’s repetitive overhead work irritated the tendons in a group of shoulder muscles called the rotator cuff. When the shoulder was designed, there was no space set aside for angry, engorged tendons.

Scott had continued to work through the pain. As with CTS or tennis elbow, working through pain is a big mistake. When your body talks to you, listen. Scott should have cut back and rested his shoulder when he first experienced pain, not a month later. Had he cut back, the problem would have probably resolved on its own. Pressing on, he added to the inflammation and swelling, compounding the problem.

As with the elbow, a hot shower beating on your shoulder, followed by some simple exercises, can loosen it up. Over-the-counter anti-inflammatories are also helpful.

Stretching an aching shoulder can restore limberness. Let the arm dangle loosely, then swing it in relaxed circles. Reverse direction every minute or so. Five minutes of this stretch, three times per day, is often helpful.

Stretching an aching shoulder can restore limberness. Let the arm dangle loosely, then swing it in relaxed circles. Reverse direction every minute or so. Five minutes of this stretch, three times per day, is often helpful.

I limited Scott’s work to waist height, put him on a prescription anti-inflammatory, injected his shoulder bursa with an anti-inflammatory and sent him to physical therapy. He improved, but it took six months. Scott will not work through pain again.

A small number of patients don’t improve with conservative treatment, and they need surgery. Typically done arthroscopically (through a tube inserted in a small incision), this surgery consists of decompressing the shoulder by cutting through the coracoacromial ligament. This outpatient surgery is usually followed by four to eight weeks of physical therapy. Full recovery normally takes four to six months.

You have probably noted that there is a common theme with all these conditions. Listen to your body, and respect your limitations. Pain requires rest.

John Fuhrman is a recently retired orthopedic surgeon who is living in Bigfork, Montana.

Photos: Andy Engel; drawings: Gary Williamson

To see the original version of the article, click the View PDF button below: