The History of Hammer Design

From rocks to titanium, hammer design has a rich history.

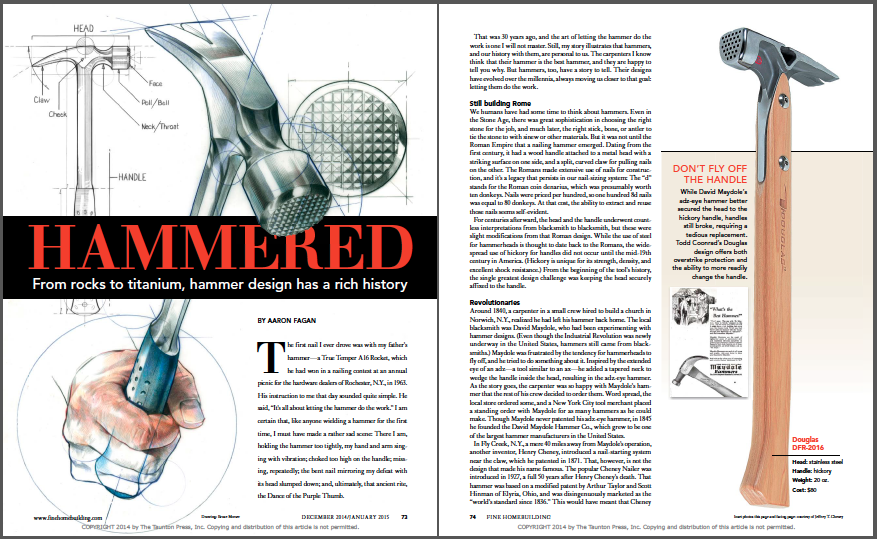

Synopsis: Hammers designs have evolved over the millennia, and they are a time capsule with a story to tell. They reflect our history and the history of their design. For example, the necessity of devoted framing crews in the the post-WWII housing boom gave rise to a tool that could meet the task: what is now known as the California framing hammer. Framing hammers began as rigging hatchets, which were the primary tools workers in California used to make wood oil derricks before World War II, but crews began cutting the blades off and welding on the claws from an old hammer. California framing hammers have short, milled faces that grab nails well; they are balanced; and they have a long hickory handle and a heavy head weight for lots of striking power. In “Hammered,” Aaron Fagan guides us through the history of hammers, from rocks and the earliest claw hammer in Rome, to David Maydole’s adz-eye hammerhead and today’s ergonomic wonders made of titanium.

The first nail I ever drove was with my father’s hammer—a True Temper A16 Rocket, which he had won in a nailing contest at an annual picnic for the hardware dealers of Rochester, N.Y., in 1963. His instruction to me that day sounded quite simple. He said, “It’s all about letting the hammer do the work.” I am certain that, like anyone wielding a hammer for the first time, I must have made a rather sad scene: There I am, holding the hammer too tightly, my hand and arm singing with vibration; choked too high on the handle; missing, repeatedly; the bent nail mirroring my defeat with its head slumped down; and, ultimately, that ancient rite, the Dance of the Purple Thumb.

That was 30 years ago, and the art of letting the hammer do the work is one I will not master. Still, my story illustrates that hammers, and our history with them, are personal to us. The carpenters I know think that their hammer is the best hammer, and they are happy to tell you why. But hammers, too, have a story to tell. Their designs have evolved over the millennia, always moving us closer to that goal: letting them do the work.

Still building Rome

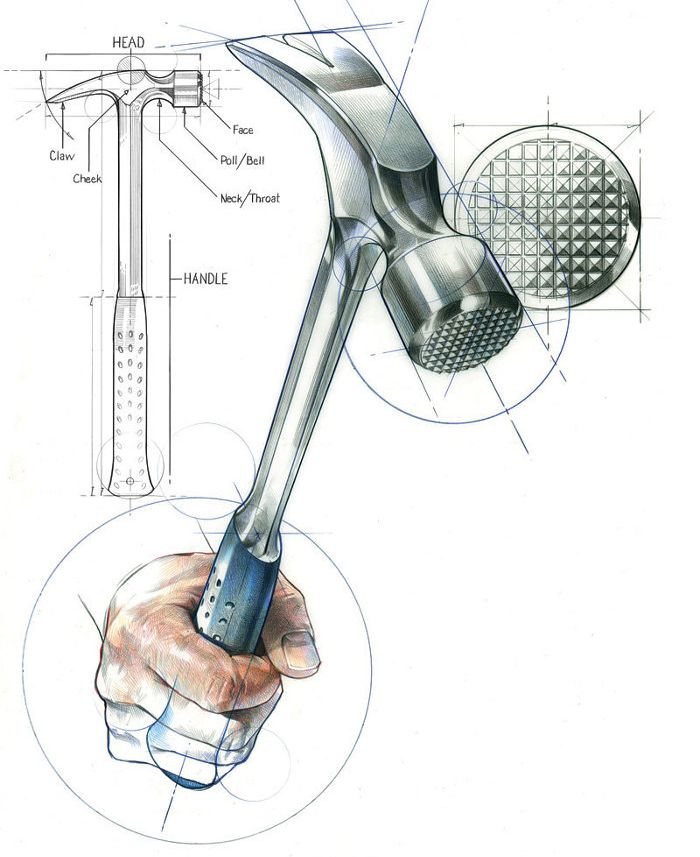

We humans have had some time to think about hammers. Even in the Stone Age, there was great sophistication in choosing the right stone for the job, and much later, the right stick, bone, or antler to tie the stone to with sinew or other materials. But it was not until the Roman Empire that a nailing hammer emerged. Dating from the first century, it had a wood handle attached to a metal head with a striking surface on one side, and a split, curved claw for pulling nails on the other. The Romans made extensive use of nails for construction, and it’s a legacy that persists in our nail-sizing system: The “d” stands for the Roman coin denarius, which was presumably worth ten donkeys. Nails were priced per hundred, so one hundred 8d nails was equal to 80 donkeys. At that cost, the ability to extract and reuse those nails seems self-evident.

For centuries afterward, the head and the handle underwent countless interpretations from blacksmith to blacksmith, but these were slight modifications from that Roman design. While the use of steel for hammerheads is thought to date back to the Romans, the widespread use of hickory for handles did not occur until the mid-19th century in America. (Hickory is unique for its strength, density, and excellent shock resistance.) From the beginning of the tool’s history, the single greatest design challenge was keeping the head securely affixed to the handle.

From Fine Homebuilding #248