Ornamental Plaster Restoration

Making an impression with traditional techniques and materials, plus a few new twists.

Synopsis: The author describes a project to restore decorative plaster work in an historic South Carolina house. This is a good summary of how ornamental plaster parts can be made with custom molds or formed in place with large templates.

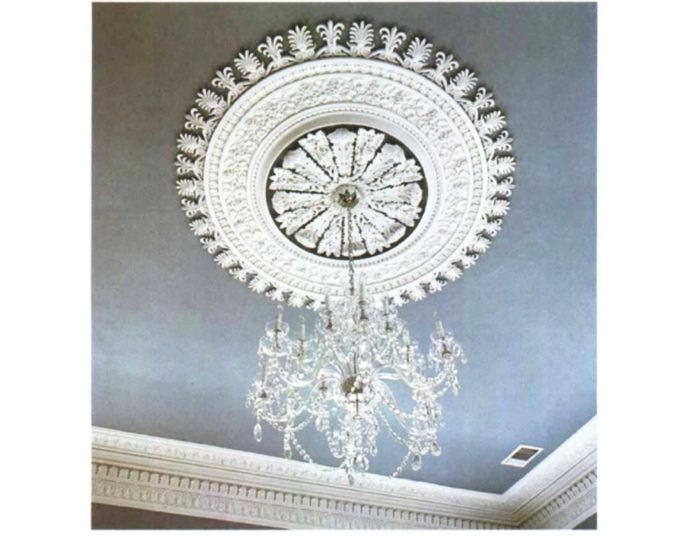

In May of 1987, I received a packet of photographs from restoration architect James H. Small of Charleston, South Carolina. Small’s photos were of badly damaged but still beautiful plasterwork from a large Regency-style house built in Charleston between 1822 and 1825 by Governor Thomas Bennett. The practice of architecture ran in Bennett’s family: his father was a noted builder-architect after the American Revolution, and his son Washington Jefferson Bennett was an architect as well. The Bennett House boasted finely detailed interior millwork, a dramatic circular staircase and robust ornamental plasterwork as sophisticated as any in Charleston.

But the passage of time challenges even the most well-crafted work to withstand the intrusion of the elements, changes of ownership and adaptive reuse. The present owners of the Bennett House, trustees of Charleston’s Roper Hospital, wished to return the house to its former grandeur. To do so a major restoration was essential, particularly of the plasterwork.

Collecting evidence

I was hired to replicate two plaster medallions: one to replace a badly damaged 5-ft. medallion in the stair hall, and the other to recreate a medallion that had once existed in the parlor but was now gone, a flat plaster ceiling in its place. I flew to Charleston to gather ornamental samples, sections and dimensions that would allow me to build the two medallions with historical accuracy. As is my standard practice, before beginning any on-site work I obtained from the owner a written release from liability in the event that further damage should result from unforeseen structural failure as I gathered samples and dimensions from the existing medallions.

It is worth noting that prior to the introduction of metal lath, the standard ceiling consisted of a three-coat plaster applied to wooden lath nailed roughly 3/8 in. apart. Ceilings of this design are remarkably sturdy but they can be jeopardized over time by a number of deleterious factors, such as inadequate keying, rusting lath nails, structural settling, water damage from leaky roofs or plumbing, nearby blasting, heavy vehicular traffic and even repeated sonic booms.

Three-coat plaster on wooden lath is very heavy and it is even weightier at the center of ornamented parlors, such as those in the Bennett House with its elaborate medallions. The wooden lath is usually continuous over a ceiling, so the failure of a part of the ceiling is likely to affect a broader area. The results of such a ceiling failure can be disastrous when the debris descends upon an irreplaceable crystal chandelier, costly china, inlaid Empire dining table and handwoven oriental carpets—not to mention the family at dinner.

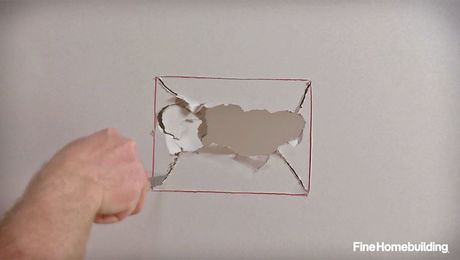

Fortunately only half the stair-hall ceiling had failed. Because the damage to the medallion had occurred during the restoration of the house, much of the debris was still on site, not in the dumpster. I spread out the fragments, photographed them and determined that the twisting acanthus leaves, canopy surround, circular fretwork and a segment of the plain-run fret border had survived the fall to the floor in a condition suitable for my work.

For more photos and details on restoring ornamental plaster, click the View PDF button below.