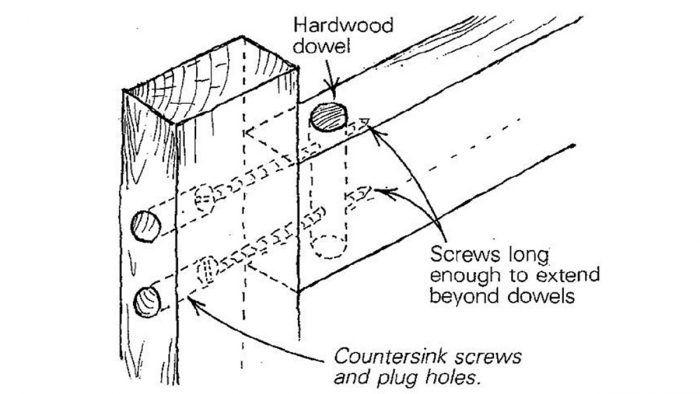

Anyone who spends much time putting together pieces of wood eventually comes across a situation where a simple screw-held butt joint would be both efficient and attractive. Unfortunately, screwing into the end grain of any wood has little holding power, and glue increases the bond only marginally. Doweling the joint is effective, but tedious. Also, dowels have no ability to pull the joint together, which screws do quite well. The problem boils down to finding a way to keep the screws from stripping out of end grain.

A simple way of overcoming this difficulty is to insert a dowel in the piece of wood receiving the screws. The dowel should be perpendicular to the butt end of the piece of wood, as shown in the drawing, where it will provide a good cross grain anchor for the screw’s threads. As a rule of thumb, I use a diameter of dowel that is about half the thickness of the stock. Pilot holes should be drilled through the dowel after it’s inserted in the hole to avoid splitting it. Screws should be long enough to extend a bit past the dowel to ensure maximum grip.

John Grunwald, Hornby Island, None

Edited and Illustrated by Charles Miller

From Fine Homebuilding #30

View Comments

Excellent tip! I typically use excessively long screws in most connections similar to this. This is especially useful when working with finish-quality connections where extra long screws run the risk of wandering through the surface.

What you have done is to duplicate a pocket hole joint with a lot more work.

A similar construct is to use metal cross dowels, also called barrel bolts/nuts. Typically threaded as 1/4-20, they could be inserted from the side in you drawing in a 5/8 sized call. These cross dowels are available in a number of sizes and threads. Their virtue is that the joint can be pulled together much tighter than by the suggested dowel and screw or a pocket hole.