In 2011, we had a remarkable year. It was the second-worst year in American history in terms of deaths from tornadoes. Spring flooding devastated parts of the Midwest. The worst drought in Texas history left the state so parched that shrinking clay soils burst hundreds of water mains, exacerbating water shortages. More than 3.7 million acres burned in the worst wildfires in that state’s history, and both Arizona and New Mexico experienced the largest wildfires in those states’ histories.

Hurricane Irene and its lingering tropical storm at the end of August dumped up to 10 in. of rain in the Northeast and devastated many places, including my hometown of Brattleboro, Vt. Hundreds of miles of roads and dozens of bridges were destroyed in Vermont. Some towns were effectively cut off from help for days or, in the most severe cases, weeks, as the damage made them inaccessible.

Then, in late October an early snowstorm knocked down trees throughout southern New England, leaving some Connecticut and Massachusetts towns without power for a week and a half.

Welcome to climate change. Climate scientists tell us that we can expect more of these sorts of problems in the years and decades ahead. Precipitation patterns will become more variable, and more of our total precipitation will be bunched into intense deluges that run off as storm water, flooding low-lying areas rather than soaking into the ground to recharge aquifers. When rains finally came to parts of Texas in January of this year, it fell in buckets, causing flooding.

While precipitation levels will increase overall due to climate change (because more water will be evaporated from the oceans and other bodies of water), some regions will become more drought-prone, including much of the western United States.

We usually think of drought affecting agriculture or inconveniencing us with lawn-watering and car-washing bans, but severe droughts will also affect our electricity grid. Roughly 89% of electricity in the United States is produced with thermo-electric power plants that rely on huge quantities of cooling water. One power plant in the Southeast had to shut down during the 2007 drought, and more than a dozen in Europe either were shut down or their output was reduced from the severe 2003 drought there.

Articles have warned that if the Texas drought lingers into the summer, power plants could well be affected, raising the specter of brownouts and rolling blackouts.

Severe weather events are not the only thing threatening our ability to survive in our homes. Political instability, terrorism, solar flares, and rising costs also have the potential to disrupt energy availability and affordability. The more complex our energy and communication infrastructure becomes, the more vulnerable it is to both natural and man-made threats.

As designers and builders, what can we do about this vulnerability? The good news is that we already know how to design and build resilient homes. Although the learning learning curve will be steep for some, the idea is simple: All homes should be able to shelter occupants safely during severe storms or other disasters and to keep them comfortable during the aftermath.

Shelter from the storm

First and foremost, we need to design and build homes that provide adequate protection from more intense storms, stronger winds, and heavier rains. Currently, the most robust storm code is the Miami-Dade County Hurricane Code, which requires extensive use of tie-down “hurricane” strapping and other features to help ensure that homes will survive severe storms. Robust codes like this one should be adopted widely in the United States.

We also should address problems with wind-driven rain by designing deeper roof overhangs to keep rainwater away from walls, installing durable gutters and downspouts, ensuring good foundation drainage with continuous perimeter drains, and mandating rain-screen siding for exterior walls. In areas where flooding is even remotely possible, we should build with materials that can dry and still be usable after getting wet.

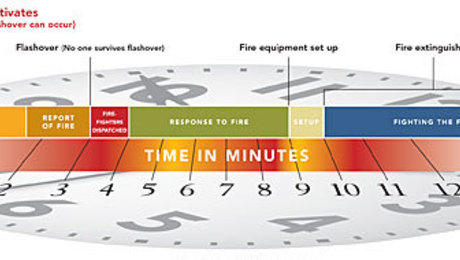

In many areas, especially in tornado-prone regions, we should consider incorporating safe rooms into basements or garages to provide shelter from even the most intense winds. There has never been a recorded storm-related death of someone in a properly built safe room. Beyond our buildings, we should raise the standards for storm-water flows, requiring larger culverts, increased infiltration areas along roadways, and restrictions on impervious surfaces to reduce runoff.

Safety in the aftermath

Most of our focus on how homes perform in the event of a natural disaster is focused on surviving the storm itself. I believe that this conversation must be extended to the aftermath of the event. Extended power outages are likely to become more common in the future, so our homes should be able to get along all right-and keep their occupants safe- even if electrical power is lost. The vast majority of existing heating systems won’t work if the power goes out. Backup generators do fine for power outages lasting up to a few days, but as we saw in the Gulf Coast after Hurricane Katrina, relying on power from backup generators for weeks on end isn’t really feasible; they run out of fuel or break down.

Keeping a home safe without supplemental heat means that it has to be extremely well insulated. Even in a cold climate like mine, it is possible to design and build homes with no supplemental heating that will never drop below about 50°F. Achieving this level of performance requires high levels of insulation, exceptional windows, and passive-solar gain.

In the U.S. Department of Energy’s climate zones 5-7, I subscribe to Building Science Corp.’s recommendations of R-5 windows, R-10 under slabs, R-20 foundation walls, R-40 walls, and R-60 attics or roofs. Such houses also should be airtight, with blower-door-measured airtightness ratings of about 1.5 air changes per hour at 50 pascals (Pa), or 0.15 cfm per sq. ft. of building shell. In hot climates (zones 1-2), I recommend R-3 windows, R-5 under slabs and on below-grade foundation walls, R-10 on above-grade foundation walls, R-20 on walls, and R-60 in attics. A good airtightness target there is 2.0 air changes per hour or 0.20 cfm per sq. ft. of building shell at 50 Pa.

With proper orientation of homes and moderate use of passive-solar gain, we can rely on solar energy to replace much of the heat that trickles out of even the most energy-efficient house. Using today’s state-of-the-art energy-modeling software, such as EnergyPlus, Energy-10, REM/Design, and PHPP (Passive House Planning Package), we can incorporate passive-solar gain and thermal mass in a way that does not cause overheating.

Power, heat, and water on hand

A further degree of resilience-beyond just preventing freezing conditions in a home-can be achieved with renewable-energy systems. In rural areas where air pollution is not a major concern, woodstoves can deliver that comfort. If the house is highly insulated, a single, modest woodstove can easily provide all the heat needed to maintain comfort during an extended power outage or loss of heating fuel. Pellet stoves are cleaner burning, but during a power outage, you need a pellet stove with DC fans that can operate on battery power (such as a Quadra-Fire Mt. Vernon AE model).

A solar electric system can provide much-needed electricity during power outages, but only if the system is designed to do so. Most grid-connected photovoltaic (PV) systems shut down when the grid goes down, so even if you have a roof full of PV modules, you may not be able to benefit from that power when you need it most. To rely on PV power during outages, you need a special inverter that works offline, and if you want electricity at night, you need a battery bank, which adds a lot to the cost of the system. I would like to see the development of simple, affordable inverters that would work when the grid is down so that we could at least operate the fridge and water pump during daylight hours.

Both solar energy and woodstoves can be used for water heating, and the two can complement one another well throughout the seasons.

In rural areas with well water, loss of electricity means loss of water. To achieve more resilient homes relative to water, the first step should be to install only the most water-efficient plumbing fixtures and appliances. Then, it is important to provide water storage-whether in 5-gal. carboys of the sort used in drinking-water dispensers or in rainwater cisterns. Consider nonpotable water sources for toilet-flushing during power outages, such as rainwater collected in buckets positioned under the roof or stream water carried into the house. In some locations, a simple hand pump may be enough to provide the water you need to survive a power outage.

Community-scale resilience

Finally, a resilient home is part of a resilient community. In a long-lasting emergency or if there were a sudden shortage of petroleum, walkable communities would be far more livable than communities defined by suburban sprawl. We designers and builders should be thinking about such issues as pedestrianfriendly streetscapes, paths for walking and cycling, mixed-use development patterns, and density targets that allow for effective public-transit options.

We also should be protecting open space and encouraging local farming to reduce our vulnerability to droughts in California or spikes in transportation fuel costs that could make the 3000-mile salad a thing of the past. Community resilience provides for local food production as well as functionality without needing to drive everywhere.

I described some extreme conditions at the beginning of this essay. To me, the threats seem real. Perhaps your area has not been affected by a severe storm, but I imagine you have lived through a few power outages in your life. A few days without electricity or heat can feel like a great hardship, but they don’t have to. If we start to consider safety and survivability in the earliest stages of design and construction, not only will we have a better chance of surviving and being able to stay in our homes during and after a disaster, but these homes likely will be more comfortable, more healthful, and more affordable to live in even if the disaster never happens.

From Fine Homebuilding #227, pp. 14-16

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

The New Carbon Architecture: Building to Cool the Climate

Musings of an Energy Nerd: Toward an Energy-Efficient Home

Graphic Guide to Frame Construction

View Comments

Oh Oh, it was cold this morning and now it is getting warmer. I heard it is going to get cold again tonight. I better get some food down to my bunker.

Did you ever hear of the ice age? It must have been from all the dino's breathing. The dust bowl of the 30's?

That must have been from all the buffalo dung.

Get real, grow up and stop being used by the Gore's of the world. They are making a fortune off of people like you.

Our military is one of the best in the world, because they are one of the best informed; once informed, they know how to plan for what they see coming. They have a lot of experience with that sort of thing. And our military is planning for the sort of climate change described in this article.

Don't be fooled by politics and special interests. There is a lot of misinformation planted in the media over global warming.

So, ignore the politicians. Ask the realists. Ask our military planners. Check out their plans, their projections, their expectations. You might change your mind about global warming and this article.