Everything Old Seems New at Taliesin West

It’s hard to tire of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work. It always seems fresh and relevant, even on a second or third visit. No matter what trends monopolize attention in current home design and construction, they seem to be played out in Wright’s buildings done many moons before.

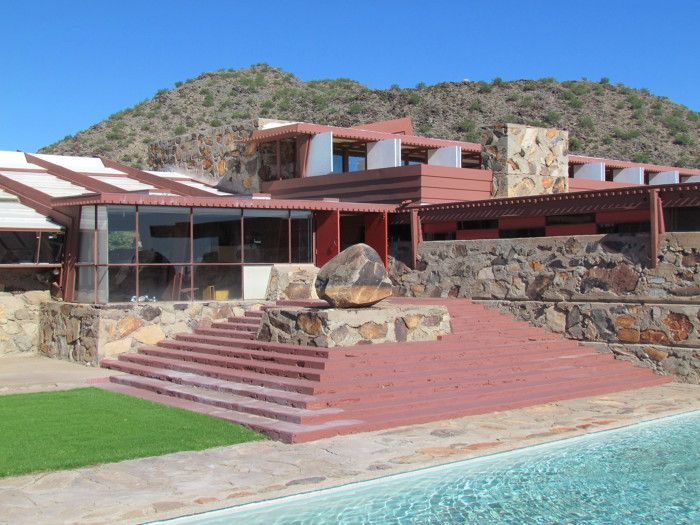

That dynamic was on display this week during a tour of Wright’s Taliesin West in the foothills of the McDowell Mountains north of Phoenix. The compound still operates as a school, training roughly 30 architecture students a year. Students used to work beside Wright himself. Now they work alongside, and within, his buildings and sitting at drafting tables in a studio he designed.

Most of the building walls were constructed with boulders found on the property, long before green standards granted points for such an endeavor. Wright would help students arrange the rocks in wood forms so that their colorful sides faced outward. To conserve on cement, the forms were first filled in with additional boulders.

The beautiful, colorful facades prove the timeless appeal of indigenous material – whether its limestone quarried from the South Hills of Texas, straw cut from the Willamette Valley, or earth scraped from the desert of New Mexico.

Wright didn’t get everything right, even though he continually tinkered with his campus. The canvas roofs that still cover some of the buildings yielded to the three inches of rain that pounded Phoenix in one hour in September. And his utilitarian kitchen design certainly didn’t anticipate the cooking and entertainment mecca that kitchens have become. His bathrooms also lack prescience.

Neverthless, most of the lessons contained in his work are still relevant. He seemed to be saying,

Let form promote function. Wright was a master at lowering ceiling heights in rooms you just pass through. Narrow, cramped hallways propel you into Wright’s garden room, where a tall ceiling and a large expanse of windows invite you to sit and enjoy the view.

Bring the outdoors inside. Most buildings are configured to promote breezes from one side to the other, though his wife later added air conditioning to the garden room. Folding doors open Mrs. Wright’s bedrooms to a walled-in, grassy courtyard.

Eliminate corners to provide uninterrupted views. Wright went out of his way to build walls that didn’t require corners for structural support, leaving glass to butt against glass. He not only wanted to break the box that dominates building forms, he also knew that people are drawn to corner views.

Celebrate geometric shapes. The best example of this may be the hexagonally shaped cabaret room, where students and faculty watched movies and listened to lectures – you can hear a whisper from the stage in the back of the room. The sunken front lawn of the compound is shaped like a triangle, mimicking the shape of the mountain backdrop.

Take advantage of views. Students working in the studio can look out windows to see Phoenix in the valley below. When he couldn’t take advantage of a natural view, Wright created one. The secluded garden room and bedrooms in Wright’s plan face an elegant interior courtyard highlighted by a moon gate.

Leave room for entertainment. Wright played the piano, and more often than not designed special places – like wall cutaways – to house the instrument. The architect also loved to watch movies and plays. Taliesin included a series of entertainment rooms.

Use inexpensive material. The walls at Taliesin were built with native stone and sand. Angular armchairs in the living room were each built from a single piece of plywood.

Add a little whimsy. The whimsical gestures at Taliesin include an unusual bell tower that announces meals, colorful poles that protrude from the side of the studio building, and Chinese theater scenes embedded in concrete posts. The gestures give the campus personality.

Make the most of natural light. Natural light, of course, is free, as long as you don’t allow so much in that you need to turn on the air conditioning. Wright used translucent canvas to cover several buildings (although it’s been replaced by plastic in many places). A roof overhang prevents unwanted sun from entering the South-facing dining hall. A window well lights the sitting room with silhouetted shapes.

It would be easy to add several other important elements to this list. Wright’s liberal use of bright Cherokee red certainly says, “Don’t be afraid of color,” and the fireplaces, ponds, and breezeways throughout the property remind us to “Celebrate the elements.”

What current trends do you think Wright presaged?

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Homebody: A Guide to Creating Spaces You Never Want to Leave

Not So Big House

A Field Guide to American Houses