When I was a builder, my partner was a licensed electrician. We did a lot of the work ourselves on the houses we built, and I got a pretty good apprenticeship in house wiring. Consequently, I’ve wired a number of panels and service connections on new houses, but until building my own garage recently, I had never done a subpanel. Like any electrical work, this is something I recommend you tackle only if you have a thorough understanding of the process, and that you pull the proper permits.

Subpanels have both similarities and differences with main panels. Both require properly sized entrance cable, from the main disconnect in the case of main panels, and from the main panel in the case of a subpanel. The conductor size depends on the amperage the subpanel’s main breaker can handle and the distance from the main panel. There are any number of online references to find that information. I had to buy about 60 ft. of cable, and considered both copper and aluminum conductors. Because copper is a better conductor than aluminum, a smaller diameter wire can be used, which makes it a lot easier to pull through conduit. However, even though I had to buy a larger gauge of aluminum conductor, it was substantially cheaper than the copper. One critical thing when using aluminum wires is to coat their ends thoroughly with Noalox to keep the aluminum from corroding where it ties to the panel. Corroded aluminum doesn’t conduct electricity well, and the extra resistance creates heat, which has caused fires.

Because the subpanel is fed from a new 100 amp breaker in the main panel, no other disconnect was required in my case, so tying in was a simple matter of clamping the wire ends to the lugs. The biggest difference between a subpanel and a main panel is that the ground and neutral buses on a subpanel have to be separated. Most panels come with a bar joining the two, which is easily removed. Code requires subpanels to have a ground connection that’s independent of the main panel’s. In my town, two 8 ft. ground rods separated by at least 6 ft. are required. With our rocky soil, they are a challenge to drive. One tip that’s served me well is to chuck the rods into a hammer drill and spin them into the ground. The combination of rotary motion and impacts seems to move the rod around most obstructions, and will even set a rod in frozen ground. And since the rods are 8 ft. long, I drive them at a 45 degree angle to avoid having to stand on a ladder initially.

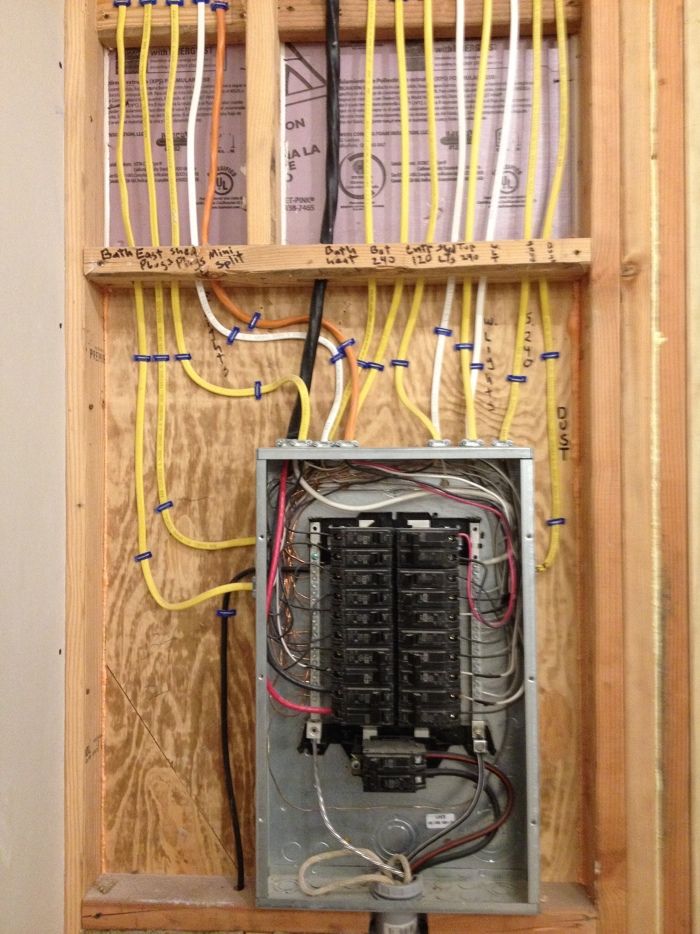

Because the ground and neutral bars are separate, all the grounding conductors have to go the grounding bus and all the neutral conductors to the neutral bus. Beyond that, there’s no difference between wiring from a subpanel and a main panel. One thing I find very helpful in either case is to mark the incoming cables with the name of the circuit they serve. That helps not only in labeling the panel, but in balancing the load between the two hot busses.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Reliable Crimp Connectors

Handy Heat Gun

Affordable IR Camera

View Comments

Just adding a consideration on sub panel. Aluminum is a lot cheaper, especially for long runs, but the size of wire needed for a typical 100 amp sub panel in garage or shed may exceed what the sub panel can handle. That is, as an example, the lug in sub panel can handle #1-4 wire, whereas you may need bring in a 1/0 wire due to the fact you have a long run.

If the sub panel is located in the same building, then 4 service wires have to go back to the main panel to complete the grounding.

I take exception to the statement that a subpanel requires its own ground rod. In fact it is only permitted in very limited cases in detached buildings, and only where there is no metallic connection back to the main building (telephone wire, copper water line, etc. ) Additionally, good grounding practice for lightning protection requires there be only one ground source for the entire electrical system. Having two grounding rods, even as close as six to eight feet apart, can direct current from a nearby lightning strike into the structure through one rod, run through the entire electrical system, and exit through the second rod. This can do enormous damage.

I can confirm that my local Electrical Code (DuPage County, just outside Chicago.. possibly an addendum from my town) requires two grounding points.

I pulled a permit for a panel upgrade and the inspector let me know he'd be happy pass me as soon as made a couple more additions, one of those being a 2nd grounding point (in addition to the line bonded to steel water line where it enters the basement). He told me all new construction in my area requires two grounds.

I was a little surprised, not because it occurred to me lightening might be a problem, but because I'm familiar with multiple ground points occasionally introducing noise into the electrical infrastructure through a ground loop.

Also now required by me, an emergency shut-off where my service enters. That's a pretty good idea, especially if you're a fireman who might have to slog through a water-soaked house with live power. If only 200A external cut-off switches weren't so expensive. :-(