Pier and Grade-Beam Foundation

Advice from a contractor on one way to build on a steep slope.

Synopsis: This is a description of a type of foundation that’s widely used on steep building sites. It consists of concrete grade beams and footings connected to pilings that go as far as 20 ft. into the ground. Not your average foundation for your not-so-average building site.

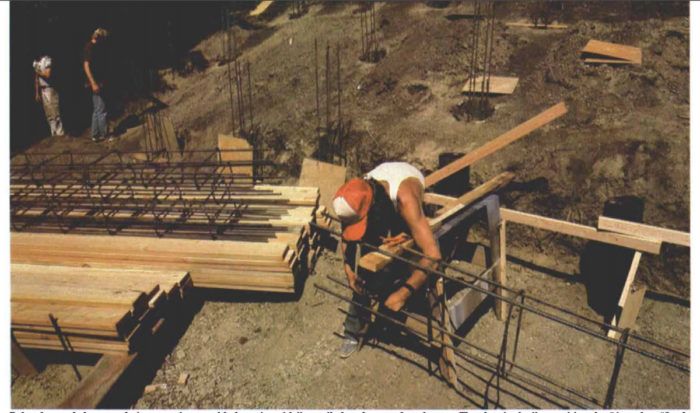

As good home sites get harder to find, many builders are looking at hillside lots that used to be considered unbuildable. A builder who can cope with the special foundations required on steep sites can often buy a lot for a modest sum, and build a house that enjoys an attractive view of the scenery below.

Here in the San Francisco Bay area, chances are good that you’ll find a pier and grade-beam foundation under just about every new hillside home. This type of foundation links a poured concrete perimeter footing to the ground with a matrix of grade beams and concrete pilings, some up to 20 ft. deep. The resulting grid grips the hillside like the roots of a giant tree. Slopes in excess of 45° can be built on with this kind of foundation. And in areas where there are landslides, expansive soils or earthquakes, a pier and grade-beam foundation may be required by local building codes.

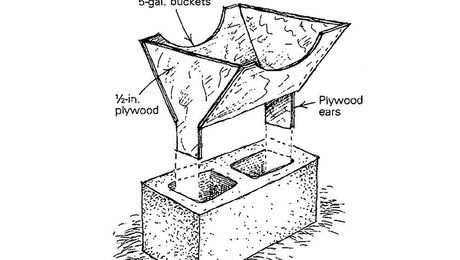

As a rule pier and grade-beam foundations need more reinforcing steel than conventional foundations, and require special concrete mixes. On the other hand, they usually call for less formwork than perimeter foundations do. What’s more, the footings for grade-beam foundations don’t have to be level.

Soil survey

A soil engineer’s report is usually required by local codes, and even if it isn’t, it’s smart to get one. Because the tendency on steep sites is to overbuild, the survey’s recommendations may reduce the number and size of piers, which designers or engineers with less knowledge of geology will spec to err on the side of caution. This kind of needless overbuilding wastes money.

To make the survey, the soil engineer will make test drillings or trenches at various spots around the site with a drill rig that typically bores a 6-in. dia. hole. Or he will bring in a backhoe. At various depths, core samples are taken with a cylinder that is lowered into the test hole. Although they will vary from site to site, these holes are usually 20 ft. deep or less because that’s the limit of most drilling rigs used to bore the finished holes. The engineer will take the soil samples back to the lab and analyze them to determine their bearing and expansion characteristics.

These tests, taken together, give a picture of the soil types and conditions at various depths, and of the natural water courses. Armed with this data, the soil engineer makes recommendations about the number and the diameter of the piers needed, and their depth. He specifies the steel-reinforcing requirements and the minimum distance between the piers. In northern California, the typical soil survey costs between $1,000 and $1,500.

Site preparation

The first order of business is to get rid of unwanted plants, loose topsoil, logs and other debris that isn’t considered a permanent part of the landscape. Once the lot is cleared, mark stumps, rocks and areas of soft, wet soil with stakes and flagging. The safety of your drill operator could depend on his knowing what’s where.

For more photos and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

All New Kitchen Ideas that Work

The New Carbon Architecture: Building to Cool the Climate

Anchor Bolt Marker