Floor Framing

With production techniques and the right materials, a solid, squeakless floor is a day's work.

Synopsis: A step-by-step guide to building a solid floor system, from laying out and attaching mudsills to nailing down the sheathing. Also included is a discussion of mid-span blocking, a subject on which many carpenters disagree.

Rough framing isn’t measured in thirty-seconds of an inch, and for good reason. Although a shabby frame can put finish carpenters in a murderous mood, it gets covered up and forgotten behind siding, drywall and paneling. But floors, if done poorly, will come back to haunt you. That squeak just outside the bedroom door is an annoyance for which there is no quick fix. But the problems can go beyond the floor itself. The blame for eaves that look like a roller coaster once the gutters are hung often rests squarely on a carelessly built floor two stories below.

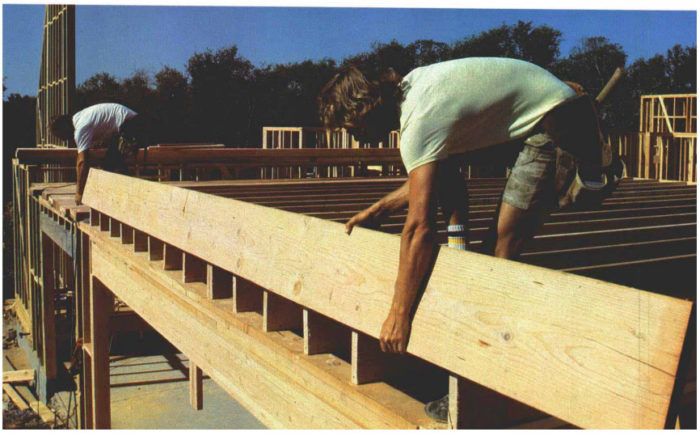

Haste doesn’t usually create these problems; using inappropriate materials and not knowing where to spend extra time does. In fact, by using production techniques and materials, rolling second-story joists (tipping them up and nailing them in place) and sheathing them with plywood on a modest sized house is a day’s work for my partner and me.

What a floor does

Most builders are very aware when they hang a door of the abuse it will get, but they don’t think in the same way about the floor they are framing. This skin is the main horizontal plane the building relies on to transfer live loads (ones that are subject to change, like furniture and people) and dead loads (primarily the weight of the structure itself) to the bearing walls, beams and foundation. Critical here is the amount of deflection in both the sheathing and the joists. The subfloor must be stiff enough to handle both general and concentrated loading, and to support the finish floor that rests on it without too much movement. But at the same time it must be flexible enough for comfortable walking and standing, something a concrete slab can never be.

Floor systems

There are many different ways to build a floor, and the preference for one system over another has a strong regional flavor. Floor trusses—either metal or wood— are becoming popular because of their prefab economy, and because they can eliminate the need for bearing walls, beams and posts by free-spanning long distances. Girder systems are still used over crawl spaces in some areas. They are generally laid 4 ft. o. c. with their ends resting on the mudsill of the foundation wall, or in pockets cast into the wall itself, or on metal hangers attached to the foundation. The interior spans of the girders are typically posted down to concrete piers. Girders are decked with either 2x T&G or very heavy plywood designed for this purpose.

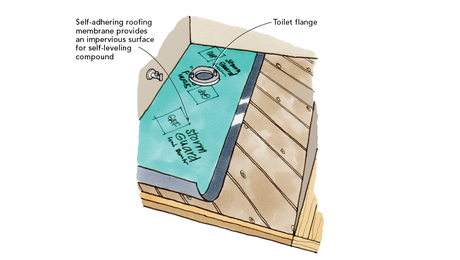

But most wood-frame houses still use joists. And whether a floor rests on foundation walls on the first story or on stud walls on a higher level, its elements are pretty much the same. Joists are typically 2x lumber, laid out on 12-in., 16-in. or 24-in. centers and nailed on edge. They are held in place on their ends by toenails to the sill or plate below, and then attached to a perimeter joist, or blocked in between. Blocking or bridging has also been used traditionally to stabilize a floor at unsupported midspans.

For more photos and information on floor framing, click the View PDF button below.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Protective Eyewear

Stabila Classic Level Set

Portable Wall Jack