Synopsis: Few carpenters know as much about traditional Western-style handsaws as Tom Law. This primer on the subject explains how to rescue an old saw, how to select the right saw for the job, and how to keep it sharp with a file.

I have a special affection for handsaws. I was taught by carpenters who used handsaws almost exclusively. My first framing job as an apprentice was a highway bridge in a remote location with no electricity; all the cutting was done with handsaws. I learned to keep mine sharp, and ended up filing saws for the entire crew. In later years, I sharpened the saws for crews of more than 25 carpenters on large commercial projects.

Even though most of the cutting I do these days on the houses I build and remodel is with power saws, I still use my handsaws. It’s surprising how often their slender profile, depth of cut, and lack of power cord make them handy. And the finest scribe-fitting I do almost always calls for a handsaw.

But because of the dominance of power saws today, few in the generation after me have learned handsaw skills. With incorrect technique and an inferior saw that is dull or badly sharpened, bandsawing can be pure drudgery. But it doesn’t need to be. The difference is in knowing how to pick out a good saw, how to joint, shape, set, and sharpen the teeth, and how to use it once it’s sharp.

Basics

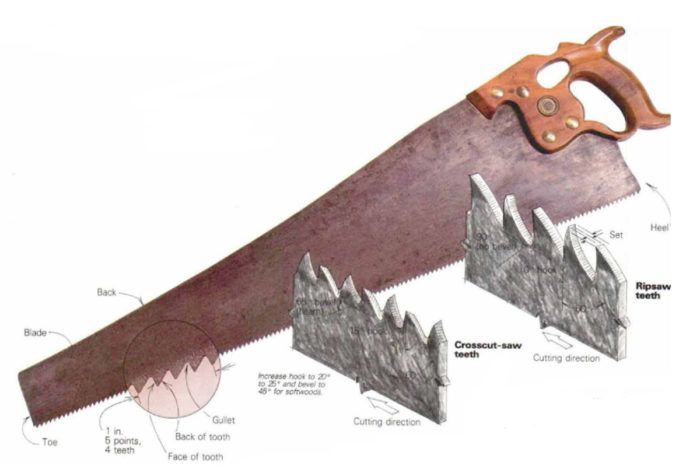

Most handsaws are about 26 in. long. Shorter ones (24 in., 22 in., or less) are called bench saws or panel saws. The top edge of the saw, called the back, can be straight or skewed. Skew-backs taper from handle to toe in a gentle S-curve; they were favored in the first part of the century. Skew-backs are better at cutting a curved line, but I still prefer square-back saws. They make good medium-length straightedges, and you can even scratch a square line across the blade and use it as a framing or combination square. The front end of the saw is the toe; the rear, down below the handle, is the heel.

One of the first things to learn is the difference between a crosscut saw and a ripsaw. Crosscut saws are made to cut across the grain, and their teeth act like a row of knife points, severing the fibers as they cut. Crosscut saws come with 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, or 12 points per inch. The more points, the finer the cut. A 7-point, for example, is used for wet rough framing; an 11- or 12-point for fine trim work.

Ripsaws, like the Disston D-8 skew-back shown above, are made to cut along the grain. Their teeth act like a row of chisels and remove small chunks of wood as they go through the cut. Ripsaws have larger teeth and deeper gullets than crosscut saws, and 4½, 5, 5½ (the most common), or 6 points per inch. You can rip with a crosscut saw, but crosscutting with a ripsaw just doesn’t work.

For more photos and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Milwaukee M18 Fuel 18v Cordless Circular Saw (2730-22)

Milwaukee Compact Cordless Router (2723-20)

BOSCH Compact Router (PR20)