Synopsis: The author provides a good introduction to architectural trim derived from classical models. It includes a glossary of terms and illustrations showing variations in proportion and style. The text provides historical background.

Moldings are structurally non-essential building elements that help ease the transitions between large, primary structural elements. In Classical Greece and Rome, these primary elements were the plinth, the column, the capital, the entablature and the pediment. Over the years, Classical orders — the interrelationship of the dimension, proportion and location of these elements — were established. Composed of both structural and non-structural elements, they became accepted as proportionately correct and aesthetically pleasing. These strict proportions were adapted much later, when a maturing and increasingly humanistic Europe turned to the Classical past for architectural inspiration.

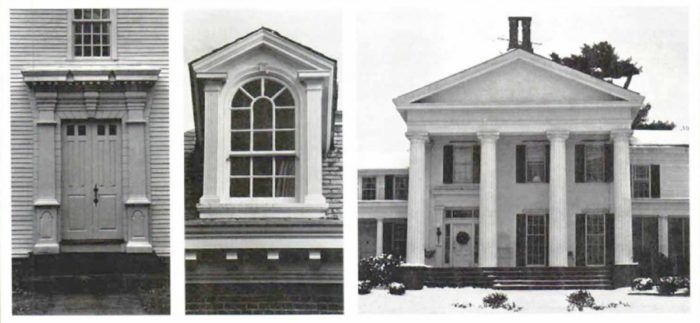

The Neo-Classical period lasted 150 years or so, and passed through several phases, known in the United States as Georgian (or Colonial), Federal and Greek Revival. There was no abrupt chronological dividing line between these styles, and in some cases overlap is apparent. The Classical forms were subject to various vernacular interpretations by country builders, who were quick to improvise. A craftsman who owned planes for making Federal moldings wouldn’t have been likely to discard these tools and get new ones just because the Greek Revival style happened to be in fashion.

Nonetheless, each of the periods is characterized by the use of particular moldings to embellish essential architectural components. These moldings are distinctly different in each period. In this article, the profiles of some of the moldings most characteristic of the different periods are drawn to scale (a profile is the combination of curved and straight parts that form a well-proportioned, graceful whole). They can help you date or restore period structures.

The Greeks and Romans carved their moldings in marble or stone, or cast them in aggregate. The inherent weaknesses in the stone were design determinants, and thus thin edges and steep projections were avoided. As a result, their moldings were often bold and bulky in section.

When Neo-Classical architecture began to catch on in late 17th-century England, however, wood was the most common material for residential building. All of these moldings were cut with wooden planes that were designed for specific profiles. Some of the simpler configurations were produced on the building site, but the larger, more elaborate ones (bed and cornice moldings and bolections, for example) required specialized planes and the expertise of the shop joiner to make them correct and consistent. Moldings were cut by hand this way until the middle of the 19th century. I do a lot of restoration and reproduction work, and I still make and use such planes.

Here’s a short primer on the characteristics of the three periods.

Georgian period (c. 1720 to 1790)

At this time, designers and builders in England were abandoning the motifs of the Jacobean period which was characterized by the use of stone and masonry in early attempts to imitate the Classical forms. Wooden houses began to replace stone, and this led to more refined Classical lines. Guidebooks were published in England which heralded the new style, called Georgian after the four Hanoverian King Georges whose reigns began in in 1714. The trend crossed the Atlantic and took hold in the increasingly prosperous Colonies, where builders were quick to abandon the older, almost medieval styles.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Cepco BoWrench Decking Tool

MicroFoam Nitrile Coated Work Gloves

Lithium-Ion Cordless Palm Nailer