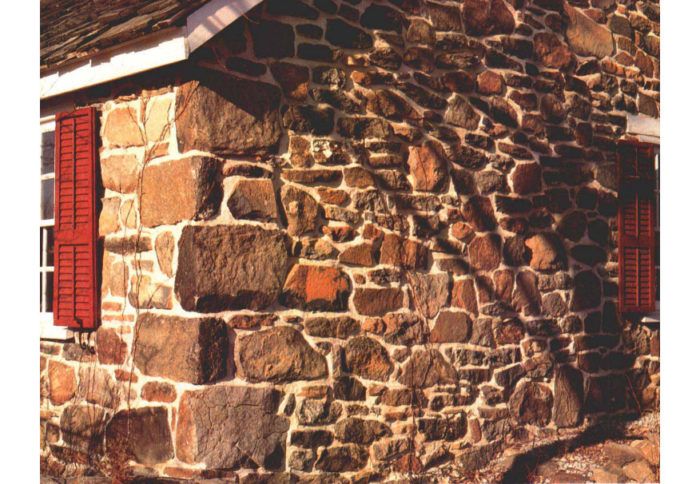

The Structural Stone Wall

Save your mortar for pointing, bed your stones in concrete, and remember there's no substitute for gravity.

Synopsis: Stone houses built these days are usually stone veneer over a wood-frame wall. Here, the author explains how he makes structural stone walls the traditional way. Stones are bedded in concrete and gaps filled with pointing mortar.

Adams County, in south-central Pennsylvania, has hundreds of stone buildings, most of them built before the days of portland cement. I got started in stonemasonry by pointing up some of these old beauties, and I’ve always been impressed with the soundness of their stonework. After nearly two centuries, these buildings are still young. The masons who built them couldn’t rely on their crude lime mortar to hold stones together. Instead, they used a far stronger glue — gravity. The stonemasonry I do today follows this old-fashioned philosophy, but fortunately I’m able to take advantage of some new materials that weren’t available 150 years ago — concrete and pointing mortar.

The trademark of my stonework is spotless pointing. A good pointing job keeps water from getting inside the wall and also provides a consistent background that can really show off the variety of textures, colors and shapes in a rock wall.

High-quality pointing mortar isn’t cheap, but I don’t use a lot of it. The jointwork extends only an inch or two into the wall. The rest — the part you can’t see — is just stone and concrete. There are a number of advantages to using concrete instead of mortar to lay up a stone wall. The most obvious is cost: mortar mix is a lot more expensive than concrete, and you’d need quite a few more bags to complete a comparably sized wall. This is because the gravel (technically known as coarse aggregate) acts as a filler in the mix, making it go twice as far without sacrificing strength. The large stones still rely on gravity to hold their position in the wall, and the concrete ensures that there will be enough space between stones for me to point later.

With a 5-gal. bucket as a measuring unit, I make and mix the concrete on site. Two buckets of sand, three buckets of gravel, 2/3 bucket of portland cement and about 1/2 bucket of water (depending on the moisture content of the sand) yields a large wheelbarrow load of concrete. I mix everything together at once except the gravel, which gets added last. The final bucket of gravel really dries up the mix, and then it’s ready to use.

Concrete also gives me greater flexibility in laying up the wall than mortar would. Without the added gravel to hold adjacent stones apart, mortar tends to squish out between joints. With a stiff mix of concrete, I can keep the mix well away from the exposed face of the wall. This leaves room in the joints for my pointing mortar and cuts down the risk of messing up the faces of the stones with squeeze-out. The concrete won’t compress with added weight even if it hasn’t set, and this allows me to work vertically without worrying about the joints collapsing. Regular mortar mix can’t stand up to much compression before it sets, so you have to work horizontally, which isn’t always convenient.

For more photos, illustrations, and details, click the View PDF button below: