Synopsis: Metal roofing specialists these days turn rolls of sheet metal into panels with specialized bending equipment and join them on the roof with the help of mechanical crimpers. Here, the author shows how a metal standing-seam room is fabricated on site and installed with relatively few hand tools and the right technique.

With a few peculiar hand tools and a knowledge of some old-time techniques, an enterprising remodeler/restorer can produce one of the most attractive and longest-lasting residential roofs around — the standing-seam metal roof. While its clean lines and unmistakable hand formed look are still admired by old house lovers, “tin roofing” has generally fallen into disuse, as roof after roof is replaced with composition shingles. This is unfortunate, because metal roofing is indispensable for solving some of the common problems of old-house roof work. For example, hand-worked metal roofing is essential when matching existing architecture with new additions. It’s great for covering cornice returns, bay window roofs and other locations you don’t want to roof again for many years. A standing seam roof is perfect for roofs too flat for shingles, yet too steep for built-up roofing. Here in western Virginia a tin roof has been the roof of choice for many years.

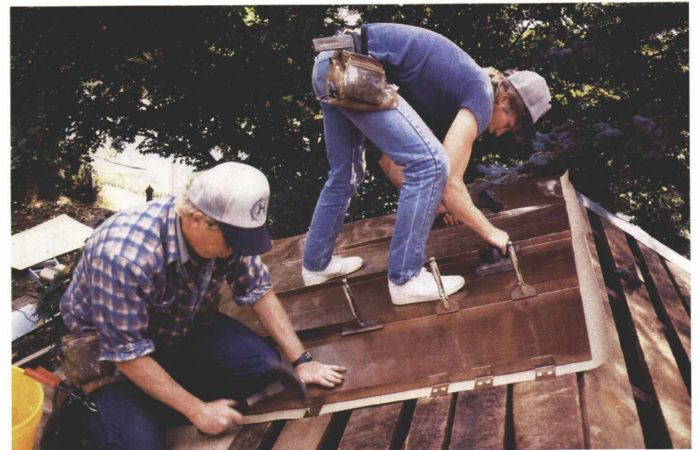

A standing-seam metal roof is really quite simple. The idea is to fold sheets of metal together to create a weather light skin, without penetrating the skin by fasteners. The metal is cut to length and bent into a “pan” having an angular, U-shaped profile. Unlike rows of shingles, pans run vertically from peak to eave. As each pan is laid on the roof deck, it is fastened with “nail cleats,” cut and formed on site from the same metal as the pans. As the pans are laid edge to edge and fastened in place, the edges are double rolled, or “locked” together by hand to create a 1-in, high standing seam. No sealants other than solder are used, except at flashings, where we sometimes use silicone caulking.

Choosing materials

A hand worked standing seam roof can be fabricated from either sheets or rolls of galvanized steel, terne (steel coated with a lead-tin alloy), copper or terne-coated stainless steel. For workability, terne and copper are best; galvanized steel is stiffer and more difficult to solder, and terne-coated stainless is stiffer yet. Copper and terne-coated stainless are the premium materials in terms of longevity — and cost. Terne (the vernacular term is “tin”) is long lasting if painted every few years. Galvanized steel can be left bare for a few years, but then it too must be painted. Whichever metal you select, use only compatible materials for nails and flashing.

My choice for a roof, at least in this area, is the terne roof, because terne is readily available, very workable and easily painted (compared to galvanized roofing, anyway). It comes in coating weights of 20 lb. and 40 lb. (the weights refer to the amount of terne coating per 100 sq. ft. of metal). Twenty-pound terne is a flashing weight; forty-pound should be used for the roofing itself. The metal also comes in two thicknesses: 30-ga. steel for general use, and 28-ga. steel for heavier use. It’s made by Follansbee Steel Corp. (Follansbee, W. Va.).

For more photos, illustrations, and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Hook Blade Roofing Knife

Roofing Gun

Shingle Ripper