Repairing Old Stonework

With the materials already delivered and paid for, why not use them?

Synopsis: Using the renovation of a pre-Civil War barn foundation as a guide, the authors explain how old stone work can be revived. They cover tools, techniques and materials used to restore stone foundations to like-new condition.

At first glance, a lot of old stone buildings and foundations look like ruins ready for bulldozing. But much of the work that went into those structures was in gathering the stones and bringing them to the site. In the case of the pre-Civil War barn foundation pictured here, we’re talking about 135 tons of carefully selected fieldstone, some of which is rough dressed with hammer and chisel. That’s an incredible head start, even if all the stones need to be relaid. And luckily, three-quarters of the stones in this foundation were still in the right position, needing only to be repointed.

The major problems were created by the rotting of the wooden lintels over the windows, which caused the stone above to collapse. Making matters worse, the top-plate timbers had decayed so thoroughly that the resulting humus supported vegetation whose roots had damaged the top course of stones.

The relaying and repointing that we did on this foundation is fairly typical of stonework repair, and seems a good occasion to note some guidelines for such work.

Bed first, point later

There are several reasons to bed stones and point the wall as separate procedures. For one, you never have to work above the finished project — you build first, then point your way down the wall without leaving a mess. By laying up and pointing down, you also avoid shocking the finished joint with big stones being set above. It is much less crucial when the bedding mud gets jarred and cracked from new work.

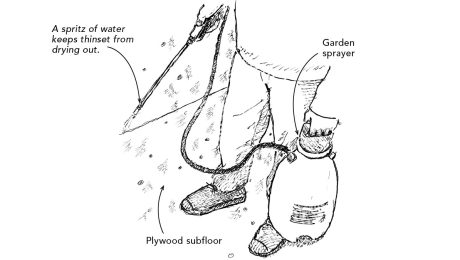

If you take this approach, you can use different mixes for bedding mortar and pointing mortar. This will allow you to fine-tune each mix for the different jobs each has to do. Another advantage of a separate bedding mix is that variables in the weather are less likely to halt production. If you go strictly by the masonry books, only about three days a year here in Pennsylvania are fit for laying stones. It’s either too hot or too cold, or there’s a chance of frost or rain. With the separate bedding approach, you can work through the bad weather, and try to do the pointing during the few good days.

Weaker is better

The bedding mix in a stone masonry wall needn’t be very sticky or have much compressive strength. A typical cubic foot of stonework weighs around 144 lb. and exerts a force of one pound per square inch (psi) on the mortar below it. At the bottom of an 8-ft. wall, the force increases to 8 psi. A two-story building on top of the wall might only double the weight. There is simply no advantage in using a mortar mix that will support thousands of pounds per square inch when all you need is 100 psi at the most. There’s no sense wasting portland cement where it isn’t needed. In fact, there are disadvantages in using bedding mortar that is too strong.

For more photos, illustrations, and details, click the View PDF button below: