Running the Company

Although 15 years old, these ideas on organization and management for builders outlined in this article are still sound

Often I’ve thought that American homebuilders could use a competitive kick in the rear from the Japanese. If the public could get homes by Toyota, kitchens by Nissan, and room additions by Honda there would be no market for the shoddy work produced by so many of our builders. Like Detroit’s car makers, more members of our industry would have to dedicate themselves to quality.

A newly completed model home I visited in an “executive” suburb here in the San Francisco Bay Area epitomized for me the sorry standards in effect even for so-called custom work. Stucco was splattered over window casings and sills. Mitered joints stood open 1/8-in. Wood shakes apparently dislodged by the summer sun had slid into a sagging gutter. Price tag: $600,000.

Poor quality on American building projects is usually blamed on the tradespeople. Home buyers speak longingly of the way houses were supposedly built ” i n the good old days . ” Architects lament the youthfulness and hell-for-leather style of carpenters. Contractors complain that responsible and capable workers are not to be found. My own sense, however, is that at least as great a problem i s the management provided by builders. Construction sites often tell the story at a glance: They sometimes resemble public dumps.

Management is a huge subject. In this brief article and the one that preceded it (FHB #44, pp. 46-49) , I’ve had to skip over topics such as estimating, contracts, the organization of an office and shop, or the writing of business plans to concentrate on practices related most directly to the efficient and workmanlike completion of individual projects.

What to be and not to be

Perhaps there are good builders who have never become good carpenters, who cannot form a foundation, raise a plumb wall or hang a door; who have not absorbed an understanding of the trades by working alongside electricians and plumbers and other subs at job sites. But it seems to me that to be a good builder you must be able to both hire and supervise good carpenters as well as contract with capable subs. To evaluate your carpenters and their work and to communicate effectively with subs, I think you need to have been personally involved with the craft.

Ironically, after investing years in the development of your carpentry skills, you must give up the tools if you want to make the transition from good carpenter to good builder. The compelling logic of the situation is this: To effectively handle larger jobs- say a new house or a sizeable addition and remodel-you need a good crew. A good crew is one that is stable and has learned to work as a team. For a crew to be stable, it must have steady work. Providing steady work means meeting prospective customers, contributing to design work, making estimates, negotiating contracts and supervising the work. Doing all this is a big job. Add the development and updating of management systems, and you’ve got a full-time job. Add carpenter’s duties and you’ve got an exhausting job.

New builders and even veterans, having long made their living with their tools, will hesitate to relinquish them as I did. They will proudly tell customers that they are not mere paper contractors but “still do the work themselves.” In fact they are likely to do too much of the work, wearing the myriad hats of salesperson, estimator, lead carpenter, supervisor, designer and bookkeeper. They are stretched so thin that they do none of their work well.

Builders who attempt to remain active carpenters often give themselves a demotion. It is nearly impossible to do complex carpentry tasks while running a company. The builder’s mind races away from the work at hand with tape, level, saw and hammer in order to deal with management considerations. He is constantly interrupted by his crew members, suppliers, subs, client, or architect. So he assigns himself less mentally taxing tasks such as nailing up blocking- the apprentice work he started out with five or ten years earlier. Instead, he should probably end his career as a carpenter and concentrate fully on giving his operation the management it needs.

In my own career in the trades, each time I began acquiring a new set of skills and tools, I got a new toolbox. Likewise, as I made my transition from carpenter to manager of my company, I acquired a new “toolbox,” this one made not of steel but of leather.

The portable office

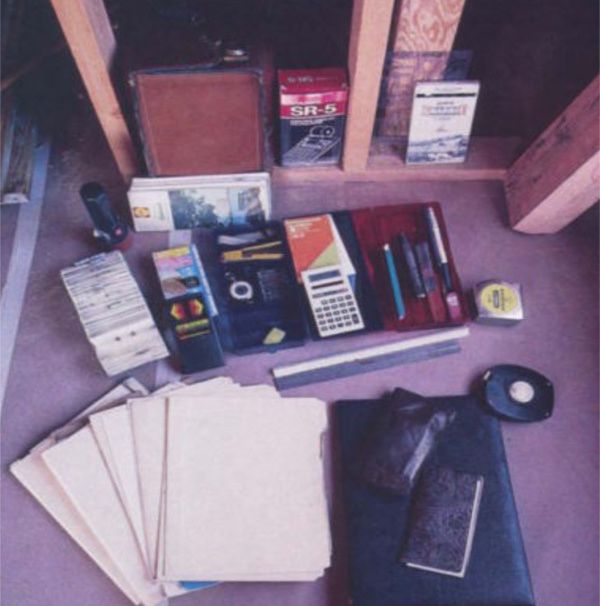

My new toolbox is a large briefcase of the type called a “catalogue” case. It is usually used by the kind of salesmen who need to carry plenty of samples and brochures. The first day I brought it to a job site, an apprentice carpenter named it “the office,” and indeed it is. Its one-cubic-foot interior contains sufficient files, forms, references and equipment for me to do my management work wherever I happen to be during the day.

The portable office is divided into a large central section and two side pockets. One pocket contains petty cash for important purchases like coffee and doughnuts, and the checkbook for my commercial account. I do attempt to have all bills sent to my office, where [ can pay them in a single check-writing session every week. Occasionally, however, a supplier with whom [ do not yet have an account wants payment on delivery, or a sub needs the favor of payment immediately upon completing his work. For such situations, I like to have the checkbook in the portable office.

I keep a large balance in my commercial account, or in a liquid-asset fund from which I can readily make transfers. A National Association of Homebuilders manual suggests that small builders keep cash on hand equal to five percent of their gross receipts. In my experience, that’s dangerously conservative. By staying around ten percent, I feel confident that I can always pay my subs, suppliers and crew promptly. There’s profit as well as satisfaction in this. Several of my suppliers give discounts for immediate payment. Subcontractors return the courtesy of prompt payment with good service on the small jobs, as well as on the big ones, and keep our company on their favored-customer list. Skilled and reliable subcontractors are offered more work than they can handle, and when they have to prune their accounts, slow-paying builders are the first to go. Finally, if carpenters can rely on a good check, they will be willing to make the commitment necessary to help a small building company stay in business.

The second side pocket of my portable office contains job files. One is for the current major job. Another is for the previous job. We try to stay on a job until it is complete, but often a few details have to be wound up after we have moved to our next project. We get back to these items as quickly as possible. Nothing diminishes a customer’s appreciation for a project well done as fast as a builder’s failure to dispatch a few final details. The presence of the previous job file in the portable

office reminds me daily to get those details done. Likewise if a call-back comes, I make it a priority. Nothing so preserves customer appreciation as a builder who takes care of a project months after he’s gotten the customer’s money.

A final job file contains notes of possible future jobs. I’ve learned that holes can open unexpectedly in our schedule, so I never assume we don’t need work. When a prospective customer calls I take down his name, telephone number and address, and a description of the job. If we are booked farther ahead than he would like to wait, I suggest I call in the future on the chance he may not find a satisfactory contractor. When we are ready to book work, I can open the future job file and find a record of a few dozen potential customers.

The big middle section of the portable office contains items I frequently need on my daily rounds. There’s a hairbrush and boot polish to spruce up for meetings with clients, following a dusty morning at a job site. There’s a 25-ft. and a 1 00-ft. tape measure, a flashlight and an electronic stud finder for checking current jobs and scoping out future ones. I also carry an assortment of office supplies and equipment: pens, pencils, erasers, a utility knife and a stapler. A packet of local street maps stands in a corner. Next to it is a copy of the Uniform Building Code.

A compact electronic calculator with printout tape sits upright in its own box. Printing calculators are a blessing (I think they are more important for small builders than a computer) . With non-printing hand calculators you can add a column of figures three times, get three results, and not know where you made your mistake. With the printing calculator you simply check your tape against your numbers and readily correct any errors. I keep a fullsized model on my desk for bookkeeping chores. The compact model in the portable office is useful for field estimates and takeoffs.

In manila folders alongside the other items in the middle section of my office, I store stationery, envelopes, W-4s, receipts, change orders and contracts. Other folders contain copies of the licenses and the insurance certificates that building departments ask to see when I go to get a permit. A folder carries my design, estimate and contract checklists. Another carries the company handouts I give to potential clients. One tells them how we do business, another lists our references and a third is a brief written by myself called, “What you need to know about your contractor.”

A final folder holds a supply of typewriter paper. It’s the only “form” I’ve ever found that is flexible enough to serve all the needs of small residential builders. I use dirt-cheap supermarket quality 8-1/2 by 11 sheets for estimates , letters, notes , job schedules, flow charts and punch lists. I customize sheets with a few ruler lines to become time boards for my crew and can throw in a few folds to create a daily reminder calendar.

The final item included in my portable office is my flip file, packed with the names and numbers of tradespeople, suppliers and other professionals. A builder’s chief function is to coordinate other peoples’ skills. The more able people he has to draw upon, the sounder his operation. I regularly expand my flip file. If I see an efficient plumber, a stucco man good at matching textures, or if I meet a carpenter with enthusiasm for his work, I add their names and phone numbers to the file. It may be years before I need their particular skills, but when I do, I’ve got a list of likely professionals to call.

My bulky case frequently amuses my clients and associates. It is equipment that is more often associated with encyclopedia salesmen than with builders. But I shrug off the chuckles it produces because the box is so valuable. It eliminates the dead time that can be the nemesis of many small builders. If I’m between appointments, I can haul my portable office into a coffee shop and work on an estimate. If a subcontractor is late for a meeting, I can pull out my checklists and compose a contract. If I need to wait for an inspector to get to a job site, I can pay my bills or knock off a day’s phone calls without having to call information or thumb through the phone book.

Hiring

Old adages and contractors’ complaints to the contrary, good help is not so hard to find. Some tradespeople want only as much pay for as little effort as possible. But the indifferent work of many comes from frustration with badly run projects. I’ve seen the performance of my own crew decline when I manage poorly. A well-run company will readily attract capable workers.

A painting contractor I know likes to hire men or women recommended by his employees. He feels that he can thereby minimize interviewing and checking of references.And he feels that if his employees already know the new h ire, they’ve got a head start toward the camaraderie that characterizes a good crew. Other contractors I know like to hire by reference from friends and acquaintances in the construction business. They call around until they find the person they need. Recently I’ve found it useful to advertise.

On the bulletin board at our lumber yard, I place a brief note (a newspaper ad would do as well). I describe the skill level we need, our pay scale and other salient features of our company, including our commitment to good craftsmanship. Even in boom years for construction, the ad has brought dozens of applicants. I telephone interview as many applicants as time allows.

First I cover the basics: “Are you a U. S. citizen? Do you have any physical or medical disabilities that would interfere with your ability to do the job?” Next I inquire about the applicant’s skills at rough and finish carpentry and other trades.

The precision with which applicants describe their experience is a good indication of their skill. Though an applicant may claim to have two years in residential construction, the one who says he has “done a lot of nailing on walls” is not a framer. The individual who has “laid out, stacked, stood, plumbed and lined a fair share” may be a framer. Beyond the skills applicants have to offer, I want to know what they want from my company. Are they looking merely to get bucks together and build up unemployment benefits for the ski season, or do they want long-term employment and a chance to advance themselves in the profession?

I liked a recent applicant for carpenter’s apprentice. He had spent two years in construction and had invested in a truck and tools. On weekends he designed and built furniture. He hoped to become a licensed builder/designer. I hired him. His description of his goals and values was impressive, and he had put his money where his mouth was.

After conducting many stiff interviews, I’ve learned not to confine an interview to my standard questions. Ideally, an interview should be a two way encounter. I encourage applicants to question me. I can learn as much from their questions as from their answers. Do they ask about safety practices? If so, chances are they will be safe workers. Do they ask if there will be opportunity to do more challenging carpentry as time passes? Chances are they will be attentive and eager-to-learn apprentices.

The most effective interview is the one that becomes a conversation. I will learn things I never would have learned in a more formal interview. One applicant impressed me in the early stages of an interview, but as we began to talk more freely, he made sneering references to “garbage” work. There is no such work in construction. Even demolition requires skill and care.

An applicant who does not help move an interview along may not be a good candidate for a construction crew. I once interviewed a helper who was exceptionally brief in his responses. But he had behind him a successful career in another trade and was eager to learn carpentry. After he had joined the crew, his reticence proved to be a serious problem. He would not participate in the camaraderie of the work site and thereby dampened the other carpenters’ spirits. His hesitancy to ask questions resulted in mistakes and s lowed his learning. After he gave notice, I realized that at his previous trade he had worked alone. His solitary nature had served him well there , but was a liability in construction. Building depends on free communication.

Before offering employment, I invite applicants for a second interview and a tryout at the job site so that I can refine my initial impressions. I ask beginning apprentices to perform a few simple tasks: drive a dozen framing nails , move a beam and a sheet of plywood, square the ends of a few blocks and cut them to specific lengths.

I like to schedule journeymen or advanced apprentices for a full day’s tryout (with pay, of course). The tryout gives my foreman a chance to thoroughly assess the applicant and gives the applicant a chance to look us over. When we commit to one another, it is for good reason, and our chances for a successful working relationship are equally good.

During the interview I ask an applicant for his opinion of our ground rules. After he or she has joined us , I expect adherence to them. The applicant will be at the job site and ready to go at the beginning of our work day. He will come to work reasonably neat and clean – no soiled or ragged clothing. Appearance contributes to our client’s confidence in our professionalism – no small comfort for people who are allowing us to rip apart their existing home or to build their new one. Builders who do not care about their appearance might also not care about their work.

We expect new employees to work safely, work steadily and work carefully-with focus. How do you know if someone is focusing? Once I watched an apprentice come down a ladder at the same time that our lead carpenter, David Lassman, came down another. David was moving carefully and, even so, reached the subfloor while the apprentice still had four rungs to go. When the apprentice got to the bottom of his ladder he realized he had forgotten his hammer at the top. Back up he went. Meanwhile David had his tape out and was measuring for a cut. The apprentice never did develop focus and we had to let him go.

Good employees go above the ground rules. They contribute ideas to improve the quality and efficiency of the work. They point out poor performances and good work by subcontractors. They establish cordial relations with clients and help to develop new work by welcoming prospective clients to job sites. They are unhappy after a bad day during which they work inefficiently or make mistakes. They are pleased when they stand back and look at tight trim work or a frame that is plumb and square. They are not only collecting a paycheck, but also are acting from the knowledge that they have a stake in the company.

Firing

Sometimes you make a mistake and hire the wrong person. Firing an employee is usually a troubling, expensive experience. You need time to find a replacement, and it takes time for that new person to get in tune with the crew. If you must fire someone, best that you not do it unilaterally. At least the main members of your crew should know that a termination is in the wind and be given a chance to comment. When someone in the company is fired abruptly by the boss, it can be demoralizing to the remaining employees. Even if they have no ground for worry, they will wonder if they, too, may be unexpectedly dismissed. From my days as a journeyman working for large companies, I recall that the carpenters inevitably approached payday with a mixture of anticipation and fear. We never knew when, along with our paycheck, we would be handed the extra slip of paper that told us we were not needed the following day. Partly as a result of such cavalier treatment, some carpenters regarded the contractors cynically and cheated and stole from them.

Pay

It is said that a difference between Toyota and its American counterparts is that Toyota regards employees as assets and American corporations look upon them as overhead. A builder should realize that along with his own skills the tradespeople who remain with his company for the long term are its most important assets. They should be paid well. A former president of L.L. Bean Company summed up the business reasons: “Paying 20% above average in wages will get you a 30% to 40% above-average employee.”

The Bean axiom must be applied with discretion. Bean operates in Maine, a state known for low wages. If a small building company applied the axiom too literally in a high-wage, unionized reg ion like the San Francisco Bay Area, it would have a net loss on every job. But the company can reasonably keep pay toward the high end for similar local construction businesses.

Pay includes more than the hourly wage. Many small building companies pay “under-the-table.” They give their employees a check based on an hourly wage, withhold no taxes, and on their tax returns, show the wages as payments to subcontractors. Sometimes contractors tell their employees they make more money by going along with this arrangement and posing as subcontractors. But that is not true. As subcontractors, the employees remain responsible for all their income tax. They must actually pay more Social Security tax than when on payroll (where the employer pays half). And, here is the kicker- using a special IRS form they can, as employees, write off the cost of their tools and working vehicle, just as they can if they are subcontractors. (Check with your income tax advisor for any current tax law changes affecting employee tool deductions.)

I’ve found most tradespeople, even those who have been persuaded erroneously that an under-the-table arrangement is more profitable, prefer to be on a legitimate payroll. They want taxes withheld from their paychecks because they do not want to be left holding the bag for estimated taxes or to participate in an illegal arrangement. (IRS rules about the distinction between a subcontractor and an employee are quite explicit. A tradesperson working under the direction of a contractor at an hourly rate is not a subcontractor.)

Benefits

Employees on legitimate payrolls receive sizeable benefits beyond their base wage and employer Social Security contributions. They are covered by disability and unemployment insurance. And while it is true that workers’ compensation insurance is independent of a contractor’s other payroll costs, employees can reasonably assume that the contractor with a legitimate payroll is more likely to keep up with his workers’ compensation premiums.

A builder should explain to his employees the value of the benefits accompanying a legitimate paycheck. In the case of my crew, the carpenters get, to begin with, a good deal on disability insurance. Their annual premium, which I withhold from their paycheck, is about $200, far less than a private policy would cost them. The Social Security, workers’ compensation coverage and unemployment insurance paid from company earnings costs about 30% of their annual base wage. That’s between $5,000 and $10,000 per carpenter, depending on individual wage rate.

Tool use is another important area of employee compensation. A modern tradesperson makes a large investment in tools. In our company, I ask the carpenters to provide their own hand tools, including power tools that cost up to $200. The company provides more expensive power equipment and utility tools such as ladders. The carpenters may use company equipment for personal projects. The company pays for the maintenance of their tools, including the cost of blade sharpening and the repair of power tools. When workers make unusually heavy use of their tools on a company project, we pay them a tool allowance.

As a small company becomes firmly established, it may have the financial strength to extend untaxed benefits such as medical, dental, or pension plans to its long term employees. As a carpenter’s pay increases, the value to him of untaxed benefits increases. If a carpenter making $16 an hour receives a raise of one dollar an hour, his take home pay (in a state with a high income tax such as California) increases by only about fifty cents per hour. But in the case of an untaxed benefit such as medical insurance, the carpenter gets the full dollar value. Put another way, though the insurance may cost the company only $100 a month, the carpenter would need $200 in additional monthly wages to buy it for himself.

Simplified Employment Pension (SEP) plans provide a straightforward way for small companies to provide employees with a retirement fund. SEPs are actually Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs). Employees establish and control their own accounts and employers pay into them. Contractors may set up SEP-IRA accounts for themselves along with those of their employees. Be sure to check with your tax advisor or the IRS before adopting the program.

The 4/3 Week

Some benefits can improve conditions for employees and the company. Company-supplied nail guns, for example, increase efficiency. They also protect carpenter’s arms from the damaging shock of hand nailing. But my personal favorite among the mutual benefits is the 4/3 week.

For the past few years, my carpenters have been on the 4/3 week, working Tuesdays through Fridays. They begin work at 7:30 a.m. and close up the site at 5:45 p.m., taking 45 minutes for lunch and a ten-minute break on company time in mid-afternoon.

Occasionally, the carpenters like to increase their paycheck by working a short day on Monday. I ask for extra days only in urgent situations such as when we need to get a foundation poured before an approaching rainstorm floods the forms. The 4/3 week loses its appeal if it is regularly stretched into exhausting (and therefore dangerous) weeks of 50 and 60 hours of work.

I so prefer the 4/3 week to the usual 5/2 that I would use it even if it were less efficient. My enthusiasm for it may cause me to exaggerate its value. But for the following reasons, I do think it provides large benefits to builder, his employees, and even clients. Set up, clean up, and breakdown time use a sizeable portion of the day. With the 4/3 week, each procedure need be performed only four times a week instead of five. If need be, the 4/3 week can be flexed so that holidays are expanded without any loss of work time. For example, because Thanksgiving falls on a Thursday, the crew can work Monday through Wednesday before Thanksgiving, and Monday through Friday the week after. They have enjoyed a four-day holiday but have still gotten in their full hours for a two week period. Similar adjustments can be made for bad weather. If rain comes on Wednesday, we can work the following Saturday, getting a day off in the middle of the week and a two-day weekend without loss of work time. Remodeling clients and neighbors of construction jobs appreciate the absence of noise and dust for an extra day each week. Most important are the psychological benefits to the crew. Working the 4/3 week helps to mitigate the, “Oh hell, it’s already Monday and I’ve got to go back to work” syndrome. Because Monday is an off-day followed by a compact work week, it does not come with such depressing speed. During the long span between Friday evening and Tuesday morning, everyone has time to become fully refreshed and return to work ready to go.

The current members of my crew like the 4/3 week. My foreman remarks that it gives him a feeling of working only one half of each week. The feeling is realistic because a week is 168 hours long, and from 7:30 a.m. on Tuesday till 5:45 p.m. on Friday is 82.25 hours, or not quite half of the week.

The 4/3 week does have drawbacks. During the short winter days the crew must spend a few minutes setting up lights to work effectively for the last hour of the day. Some tradespeople prefer the standard five-day week. Their problem is not that they find the ten-hour day too tiring. (It really isn’t; workers readily adjust to it.) They are unable to fill the long off-period and experience anxiety and boredom. It seems reasonable to conclude that the people who have sufficient motivation to use the free time offered by the 4/3 week are also likely to be superior employees. When I advertise for help, I emphasize the 4/3 week. It draws applicants more than any other feature of our company.