Synopsis: It’s no fun discovering extensive rot beneath the siding where a house meets its foundation, but the author walks through the process of removing a rotten timber mudsill and replacing it with new material. He offers a number of construction details that will keep water out and rot at bay in the future.

The heavy clay soil of northern Vermont is notorious for its poor drainage. Before the era of the backhoe and dump truck, foundation walls were usually backfilled with the soil taken from the cellar excavation. If this happened to be gravelly soil, then the dry-laid fieldstone foundation walls would remain in place. If not, they would inevitably begin to heave inward.

Another problem with these dry-laid foundation walls became apparent each spring as the water table rose, or especially after a heavy rain; water washed into the cellar through the cracks between the stones.

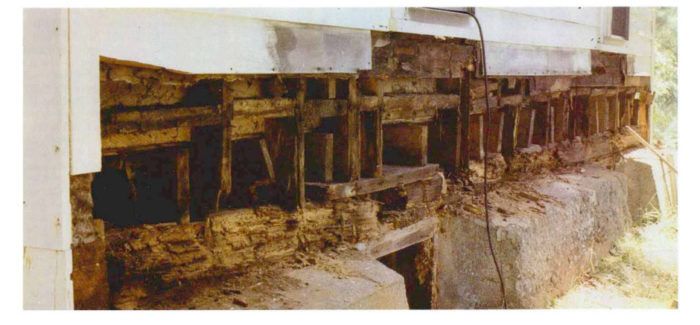

Heavy equipment and transit-mix concrete allow present-day renovators to remove a failed foundation and replace it. Carpenters of an earlier generation did not have this luxury. In the attempt to shore up a heaved wall or to prevent water infiltration, they would often pour a sloped concrete wall directly against the old stone; sometimes on the inside, but more typically on the outside. This “buttress” wall would sometimes extend to the bottom of the foundation, but it would often end wherever the ditch diggers felt was deep enough.

The bulky, spalling buttress wall was the first thing I noticed about the house that Will Leas and Lisa Dimondstein hired me to help renovate. The house had begun life as a hunting camp some 50 years ago. Over time the camp had been tinkered with and remodeled until it was almost a regular house. The Dimondsteins were following a long tradition when they decided to give the house a facelift and upgrade its energy efficiency. Leas had discovered and repaired a section of rotten sill along one wall the previous year and suspected that there might be more decay behind the mildewed clapboards on the remaining walls.

Finding fault

Structural rot is not always apparent. When probed with an awl from the cellar side, the timber sills felt as solid as new wood. There was no evidence here of rot caused by a dank, unventilated cellar. On the outside, however, the bottom edge of the siding was punky where it slipped behind the top of the buttress wall. I was hoping that a simple flashing installed over the concrete and up under the first course of clapboards might be all that was needed to halt damage.

We inserted flat bars under the edge of the second course of siding, loosened the nails and removed the first clapboard. Like a vampire shrinking from the noonday sun, the freshly exposed sheathing board virtually crumbled into compost as it was revealed. The next clapboard was removed, and yet another. Still the decay continued upward, joining a vein of rot that had begun under the window sills. I was beginning to wonder what had held those clapboards on the wall.

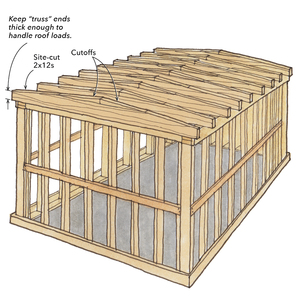

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Speed Square

Guardian Fall Protection Pee Vee

Bluetooth Earmuffs