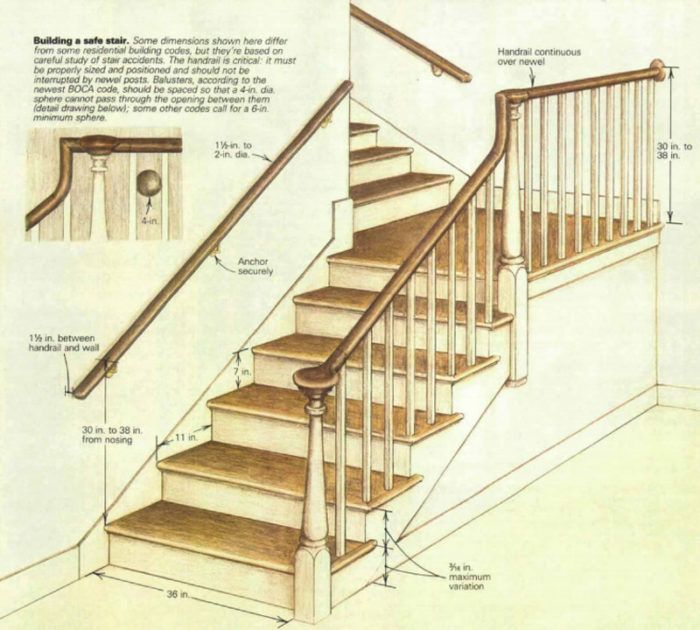

Summary: An engineer discusses a variety of design details that go into making stairs that don’t contribute to falls and injury. Among other issues, he covers baluster spacing, railing design, and the relationship of risers to treads.

What could be simpler than building a stair? Consider, for a moment, statistics from the National Safety Council and the Consumer Product Safety Commission: over 13,000 Americans die each year because of falls, with 3,800 killed on stairs each year. About 2.5 million stair falls are tallied each year, and 800,000 of them result in injuries that require professional medical care. However, because injuries can be treated in other than emergency rooms,it’s probable that this figure is low — some published estimates put the true figure at more than 2 million serious injuries. Simply put, stairs are the most dangerous architectural feature in a house. It doesn’t take much thought to realize that this problem is one that architects, engineers and builders create, and that it’s also one they can readily solve.

In the course of my work as a safety engineer, expert witness and design consultant, I have studied thousands of stairs and hundreds of fall accidents. If you design, specify, sell, or build stairs, I suspect that the subject of this article won’t immediately arouse your interest. But I submit that a lawsuit for wrongful death or severe bodily injury caused by “your” stairway would.

The role of the codes

The philosophy of model building codes has been to relax stair safety requirements for one- and two- family dwellings, even though that’s where the majority of fatalities occur. Why this is so is not clear, but the code agencies in general have a record that reflects a resistance to code changes affecting personal safety. Perhaps this is because professional safety engineers aren’t typically consulted, or because the process of code development reduces the output to the lowest common denominator. The bottom line,though, is this: codes contain technical errors,and no code can anticipate every condition in the field, so don’t rely on a building code or standard alone to guide the design or construction of stairs. Compliance with the codes is not a defense against negligence per se, contrary to what most architects and builders think. As one well-known trial attorney put it, “Codified negligence is still negligence.”

Basic stair design

Based on my experience, I believe a safe stairway, whether in commercial or residential use, should have the following characteristics:

1. Reachable, continuously graspable, and structurally stable handrails on both sides,with intermediate handrails as required;

2. Properly proportioned risers and treads with close tolerances;

3. Slip-resistant treads and nosings;

4. Adequate lighting, appropriately located and controlled;

5. Guardrails (and toe boards on steps if open on the side);

6. General compliance with the NFPA Life Safety Code; and

7. At least three steps.

There are other factors that, while not pertaining directly to the design of stairways, can figure into the safety equation. The stairs should be properly maintained, for example, with no loose treads or wobbly handrails. And there shouldn’t be any environmentally triggered factors that could distract the stair user, such as mirrors or HVAC ducts that might suddenly blow air at a stair user.

Most of the requirements above seem to be the stuff of common sense, but several are so important that I’d like to explain them in detail: handrail design, tread/riser design, slip-resistance, short runs, and guardrails.

For more detail and photos, click the View PDF button below.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Original Speed Square

Anchor Bolt Marker

Smart String Line