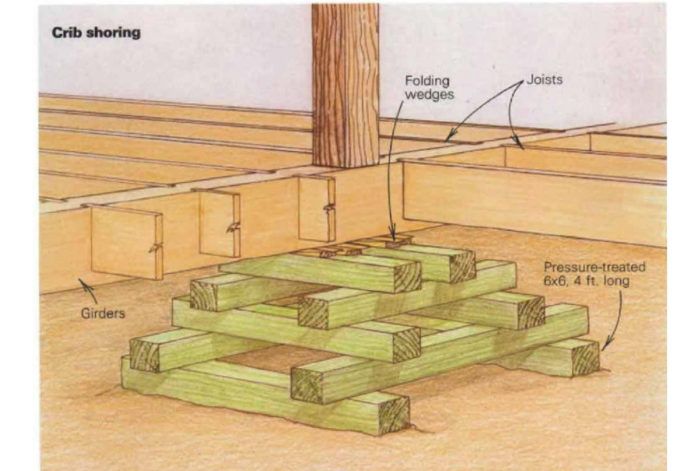

Synopsis: Making structural repairs to buildings often requires temporary bracing that supports the building’s weight while sills, beams or other components are replaced. This article details three methods.

On my last three jobs the clients were more impressed by my shoring methods than by the repairs I made. Not that there was anything wrong with my work; they liked that well enough. But in each case, selling the clients on the shoring techniques convinced them I could do the job in the first place. In this article I’ll describe the shoring techniques that I used on each of the three jobs. These methods are low-tech — they don’t require much equipment — but they get the job done quickly and safely.

Simple shoring

The first job involved simply raising the ceiling and roof of a 70-ft. long veranda so that, among other things, new porch columns could be put in place. For this job, I used a simple shoring technique.

My crew and I were restoring Helmwood Hall, a 150-year-old house in Shelby County, Kentucky, that’s on the National Historical Register. Everything had to go up evenly, smoothly and gently. We didn’t use hydraulic or screw jacks to raise the roof because they would have been in the way of our work. Also, with hydraulics it’s easy to pump one time too many and break something, and these were brittle timbers we were dealing with.

Because the porch was a trabeated structure — that is, designed to transfer the weight of the structure to the foundation down each column — and because we had to lift this weight to make our repairs, we dug 2-ft. wide holes for temporary footings about 4 ft. in front of the porch. Then we built wood footings, using a layer of 2x10s. The 2x10s bear on a series of spiles driven into the ground at an angle so that the bottoms of the jack posts could be cut square. Spiles are long stakes that we make from 2x4s or 2x6s and sharpen by cutting a taper on one edge at an acute angle of 15° or 20°. When driven into the ground with the tapered edge up, spiles compact the soil beneath them.

We notched the tops of the jack posts with a cut like a bird’s-mouth cut to engage the bottom corner of the fascia at the juncture of a ceiling joist and a rafter; we positioned the mat such an angle that we could work conveniently under and around them. The jack-post angle can vary, and the safest angles are those that are closest to plumb — the farther away from plumb, the greater the hazard. Of course, all shoring methods are potentially dangerous, and safety is the most important consideration. Sizes of timbers must be designed with a large safety factor in mind.

The jack posts were designed to be strong enough to lift the weight without distorting. We laminated them out of four 2x8s nailed together so the posts would have a wide foot to stand on. Leonardo Da Vinci long ago discovered that a bundle of saplings bound together would support more than a solid post of the same diameter.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below: