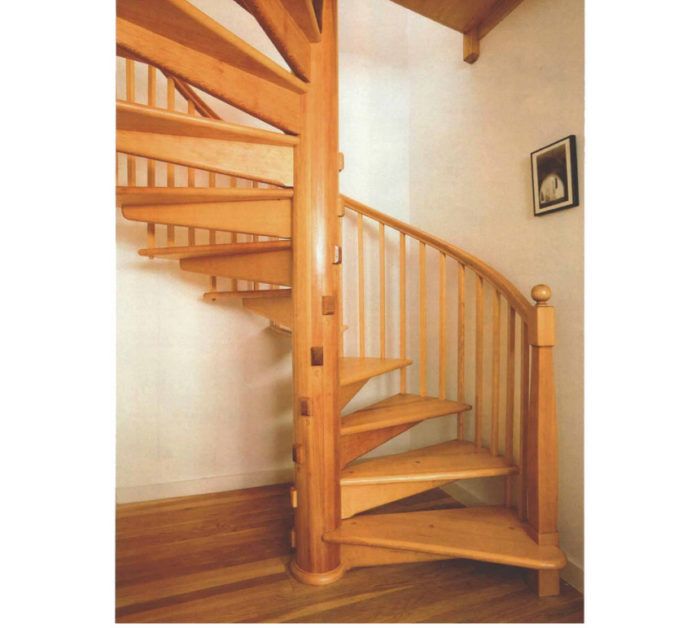

A Freestanding Spiral Stair

Using stock lumber and common shop tools to build an elegant circular staircase.

Synopsis: A woodworker describes construction of a free-standing spiral stair made with a coopered central post, stair treads that slip into mortises, and a laminated handrail. A sidebar provides the math you’ll need for layout.

As a woodworker, I have always liked curved staircases because they combine function with graceful, sculptural beauty. A spiral stair built around a central column is the simplest version of a curved staircase, but it’s still a challenge to build. In this article I’ll talk about a spiral stair that I’ve built for several clients and the straightforward techniques I’ve developed for fabricating its parts with common shop tools.

Lightening the visual load

To my eye, most pole-supported spiral stairs are aesthetically flawed because they lack a graceful balustrade. Their handrails and balusters are often used as part of the structural support of the stair, and as a result they can look pretty clunky. To avoid this problem, my stair transfers the loads from the treads by way of cantilevered ribs that pass through a hollow column. This allows me to border the stair with a delicate row of balusters supporting a sinewy handrail.

Each tread/rib assembly resists three forces: the downward load of a person; twisting due to offset loading on the tread (the fact that a person would step near the front of a tread rather than directly over the rib); and horizontal, or back-and-forth, wiggle.

To resist the downward load, I use a strong, cantilevered rib that passes completely through the column and out the opposite side. Such a design transfers the load from the tread to purely vertical reactions on the column. It also allows the ribs to be revealed as tenons on the side opposite the treads. I put 1/2-in. chamfers on these tenons, emphasizing their sculptural qualities as they spiral from floor to floor.

For a 36-in. radius stair, I’ve found that a 2-in. by 6 1/2-in. rib is adequately strong. Because the stresses on a cantilevered beam decrease with distance from the point of cantilever, I taper the ribs for the sake of appearance.

I also know that a 2-in. by 6 1/2-in. rib will sufficiently resist twisting at its outer end, and that treads made from solid 2x lumber will be strong enough to withstand the offset load. To minimize horizontal wiggle, I rely primarily on the tread itself being drawn tightly against the column with lag screws. In addition, I run the front baluster of each tread through the tread and into the tread below. This interlocks all the treads and further reduces any wiggle.

For the stair featured in this article, I used vertical-grain Douglas fir throughout, which is a strong, attractive and economical wood. Incidentally, I bought unsurfaced stock for the ribs because it’s a full 2 in. thick. Then I dressed it myself, netting ribs 1 13/16 in. thick.

Cylindrical column

The center column is round, with 24 mortises (two for each rib) in a precise spiral. To effect this, I built a 14-sided coopered cylinder in which the width of each stave is the same width as a rib.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below: