Basic Scribing Techniques

Finish carpenter Jim Tolpin shares his secrets for fitting trim to uneven, unlevel, or unplumb surfaces.

Synopsis: Scribing is the art of joining building materials snugly to irregular surfaces. This article, written by a finish carpenter, lists a number of tips and techniques for getting trim, wainscoting, and flooring to fit perfectly, even when adjoining surfaces don’t.

The first thing I learned as a finish carpenter was that square corners, plumb walls and level floors and ceilings don’t exist on this planet. And because that’s just the way it is, it was up to me to learn how to work with these unfortunate divergences from the way it ought to be. As the finish man, my job was to fit the pretty stuff to the structures that framers and rockers left behind, no matter how crooked they were.

In my quest for perfect fits, I learned how to use bevel squares and base hooks, among other tools, and became proficient in the use of a slightly customized pencil compass. I learned from legendary boat builder Bud Macintosh how to use something called a spiling batten to solve certain awkward scribing problems, such as fitting the last ceiling board. I even paid homage to the linoleum trade and learned the ingeniously simple “Joe Frogger” method of creating a template that can produce dead-accurate fits every time.

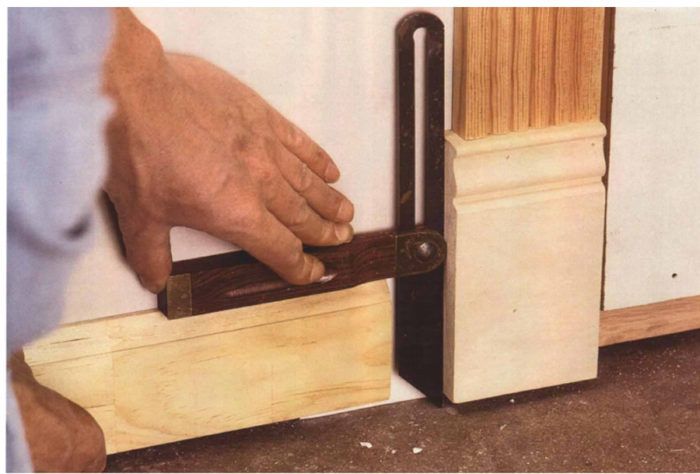

Using the bevel square

A bevel square is a layout tool with a wood, metal or plastic body having an adjustable metal blade attached to one end. The square is used mostly for determining the angle at which a piece of trim needs to be cut to fit tightly against a surface.

My first bevel square came from my grandfather. It’s a nice rosewood-bodied job with a 6-in. long blade. It’s pretty and has sentimental value, but like many contemporary bevel squares, it’s not the best tool for taking angles. This is because its locking lever, which is located at the pivot point of the tool, often sticks beyond the edge of the body and gets in the way. Also, the body is quite thick, which holds the blade away from the stock. This can throw off the angle measurement. What’s more, the body is relatively short, which can also produce inaccurate readings.

I like my all-metal Japanese bevel square better. It’s much thinner than a conventional bevel square; the lock is a knurled knob that’s out of the way; and it can be held and locked with one hand.

Although the use of a bevel square may seem straightforward, it’s not. Always extend the blade fully before pressing the outside edge of the body against a surface to measure an angle (such as when measuring an inside corner where two walls meet). Any protrusion of the blade beyond the outside edge of the body will hold the body away from the surface it’s resting against, throwing off the angle reading.

For more photos and details on scribing techniques, click the View PDF button below.