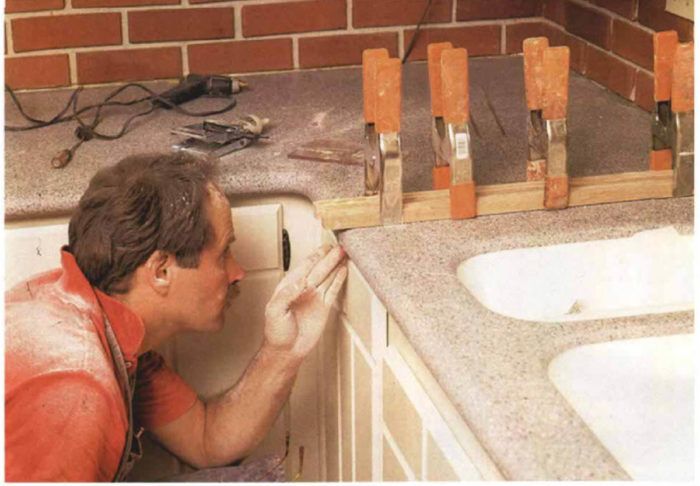

Making a Solid-Surface Countertop

Synthetic materials can be worked like wood and polished like stone.

Synopsis: Albuquerque woodworker Sven Hanson takes the mystery out of fabricating countertops from solid surface material such as Corian. He covers the whole process, from gluing and polishing to cutting in sinks. If you’ve never worked with solid surfacing, this is a good primer on the topic.

Twenty years ago DuPont introduced Corian, the first solid-surface countertop material, to the building community. It was received with a chorus of yawns. On the one hand, it looked like stone but wasn’t the real thing. On the other, it resembled plastic laminate while costing three to four times more money.

But this neither fish-nor-fowl quality of the material doesn’t tell the whole story. The most desirable aspects of solid-surface material are its workability and durability. Unlike laminate, the color and pattern of solid-surface countertops go all the way through the material, which means it lasts longer and can be repaired easily. The material is almost as dense as stone — in the range of 100 lb. per cu. ft. But unlike stone, it can be glued up with imperceptible seams and cut and shaped with carbide woodworking tools. And as more colors and patterns have come on the market, the once-reluctant public has embraced solid-surface countertops in a big way.

Corian, which is made of acrylic plastic mixed with a powdered clay filler called aluminum trihydrate (ATM), now has competition. Other brands of solid-surface material, such as Avonite, Surell and Gibralter, are made of polyester resin and the same ATH filler and color-fast pigments. The working properties of the materials, however, are the same. And even the distributors say that, once installed, the main difference between brands is pattern.

All of the manufacturers offer seminars on working with their material, and you typically need to take a course before you can buy the goods. That’s because manufacturers are understandably nervous about bad fabrication practices infecting the reputation of their products.

When I started building solid-surface kitchens, I liked the patterns and colors of Avonite’s materials. So three years ago I took their one-day certification class. It cost $50, most of which I made back in doughnuts, soft drinks and router tricks.

Since that introduction to the material, I’ve made a lot of kitchen counters and lavatory tops, and I’ve taken Avonite’s advanced class. I’ve found the material to be surprisingly workable, and mistakes are pretty easy to fix, which is no small consideration when the material costs $15 per sq. ft. and up. This article is about the basics, and I’ll focus on a typical kitchen counter to illustrate the tools and the techniques for working solid-surface materials.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Anchor Bolt Marker

Plate Level

Original Speed Square