Q:

I am about to build a western red-cedar log house. The plan calls for a conventionally framed gable roof with horizontal-log gable ends. The problem is that when the end walls shrink, the roof could twist and fail. How can this type of roof be framed independent of the wall movement?

Stan Merchant, Alexandria, VA

A:

Robert Wood Chambers, a log-home builder in River Falls, Wisconsin, replies: Personally, I would not build horizontal-log gable-end walls unless historical authenticity absolutely required it. Such walls can be built—by experts—but even experts shun them. Here’s why.

The problem, as you realize, is that log walls settle, a process caused by wood shrinkage, compression, and slumping brought about by checking (cracking) of logs. Log walls settle in proportion to their height—about 3/4 in. per ft. for green logs.

A log gable wall is a triangle in elevation; its maximum height is under the ridge, and it tapers down to zero height at the eaves walls. This triangular shape results in differential settling: Under the ridge you will have a great deal of settling while at the eaves you will have none. In essence, differential settling will cause the roof pitch to change over time—if it starts out at 12-in-12, it could end up at 11-in-12.

Unless you allow for the change in roof pitch, the roof will rack, the plate logs on the eaves walls will be pushed out, roof flashings may fail, air and rain will infiltrate, and there may be problems far worse.

True log gable walls bear the roof load, which in turn keeps the end walls tight. It takes a lot of expertise to frame a roof that bears on horizontallog gable ends. To begin with, you need a structural ridge—a wooden member strong enough to carry about half the roof load. Hire an engineer or an architect to specify this member. Provide midspan support posts for this ridge as needed. You will need screw jacks (this kind of jack has a plate on a screw for lifting) to adjust the lengths of the midspan support posts as the ridge settles with the shrinking gable walls; get the engineer to specify the screw jacks, too.

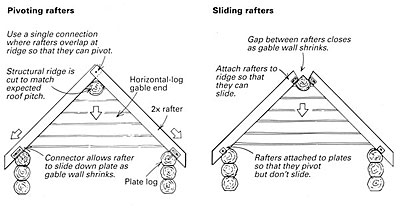

At the peak, the conventional 2x rafters must be allowed to change pitch. Perhaps the best way is to lap them over the structural ridge and bolt them to each other with just one bolt so that they can pivot. Again, get an engineer to tell you how to make this connection safely. If you use more than one bolt, the rafters won’t pivot.

The top of the ridge should be cut to match the peak of the roof. The angles you cut should be the expected pitch after settling, not the roof pitch as designed and built. To calculate your expected pitch, measure the height (in feet) of the gable end as built, multiply it by 3/4 in. and subtract the product from the as-built gable height. For example, if the as-built gable is 10 ft. high, you can expect it to shrink 7-1/2 in., and your pitch will change accordingl

The next problem is that as the roof loses pitch because of this shrinkage, the 2x rafters will want to slide down and out on the building. Therefore, the rafters must not be conventionally nailed directly to the plate logs or to any midspan supports, such as purlins. Have a metal fabricator build custom brackets that will allow the rafters to slide down the purlins and the plate logs and still provide sufficient resistance to uplift. Again, you’ll want an engineer to design these brackets for you.

Columns that penetrate the roof, such as chimneys and plumbing vents, must be carefully designed and built—remember that the roof is essentially sliding downhill. And if you don’t leave extra space on the uphill side of the framed chimney opening, the sliding roof could push your chimney over. I do not know any way to prevent the plumbing vents from being pushed out of plumb because they must be attached to the roof. Your gutters and downspouts will be affected as well.

An alternative method is to fasten the rafters to the eaves plate logs and not let the rafters slide down. You’ll have to leave a gap between the rafters over the ridge. Then, as the gable logs settle and shrink, the rafters slide toward each other at the top, closing the gap.

However, the gap causes its own problems, such as how to flash the roofing over the gap to prevent leaks. And if the roof is steeper than about 6-in-12, you’ll get a lot of differential shrinkage, so the gap between the rafters must be quite wide (it can easily be more than 16 in.), and the structural ridge has to be wide enough to support the rafters before settling brings them closer together. Again, cut the ridge to match the expected roof pitch.

Building log gable ends is perhaps the most difficult design problem in log-home construction. My advice to you is to frame the gable walls conventionally or use log posts to support log purlins and a ridge—but do not use horizontal logs to make your gable walls. If you want the appearance of logs on the gable ends, then bolt halflogs to a conventionally framed wall. This may seem like a cop-out, but keep in mind all the horrors you’ll avoid.