Air and Vapor Barriers

Understanding and preventing moisture movement are the first steps in protecting a house from water damage.

Synopsis: This overview of how air and vapor barriers work in different climates is a first step to understanding a very complex topic. It’s not a comprehensive treatment, but it will get you started. A sidebar describes construction of an airtight house in Canada where temperature extremes magnify moisture problems.

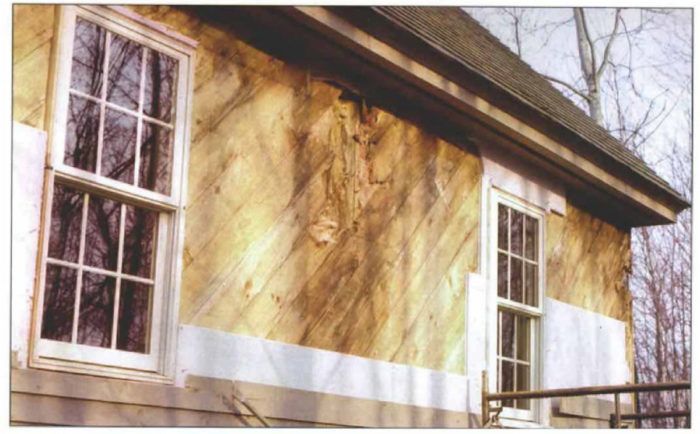

Bob Thurrell’s callback from hell began with a phone conversation sometime in the fall of 1987. The call concerned a timber-frame house that Thurrell and his partner had built five years earlier in Falmouth, Maine. The owners wanted an addition, and the builder they hired to do the work was on the phone… with a problem. After stripping some siding from the back of the house, the builder had found sheathing and structural timbers so rotten the wood could be pulled apart by hand.

Thurrell couldn’t believe it. The house had been a labor of love. Despite his subsequent efforts to repair the damage, the dispute with the owners eventually landed in court. The house that Thurrell’s young timber-framing company had built to last two centuries would last only another two years. Arguing that the house was rotten to the core, the owners won $50,000 from Thurrell’s insurance company and tore it down. He still has an album full of snapshots taken just after the house was finished. Looking at them made me a little uncomfortable. It was like being shown pictures of a friend’s dead uncle.

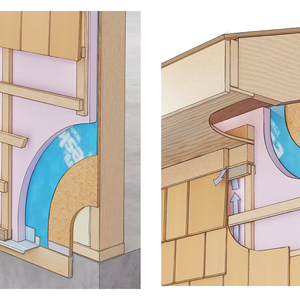

What happened? There probably isn’t any single answer. Thurrell had installed a 6-mil polyethylene air/vapor barrier on the warm side of 2×4 stud walls built between the timbers. On the outside, T&G board sheathing was wrapped in 1 in. of extruded polystyrene insulation. But the house wasn’t airtight. The green hemlock timber frame shrank as it dried out and opened gaps of up to 1/8 in. between the 2×4 walls and the hemlock frame. Moreover, interior humidity was driven up by an unvented clothes dryer and by firewood drying in the basement. The structural damage in the walls of the house is a testament to how building components (including air/vapor barriers) and indoor moisture can, under the right conditions, conspire to seriously harm a building’s structural integrity.

With a few exceptions, such as the Maine house I just described, reports of pervasive moisture damage are rare. That’s the good news. The bad news is that moisture problems, even on a small scale, are still problems you must deal with. Mold, mildew and rot are possible consequences of uncontrolled air leaks or incorrectly installed vapor barriers when coupled with high humidity. Unfortunately, there’s no single rule for installing air/vapor barriers that works for all houses in all climates. An air/vapor barrier installed correctly in Minnesota, for instance, could be a disaster for a house built on a Mississippi bayou. The truth is that air/vapor barriers are only part of the answer to controlling the moisture that can damage houses. Ventilation, indoor humidity and overall construction quality all are just as important. Some would argue more important.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below: