Flashing Walls

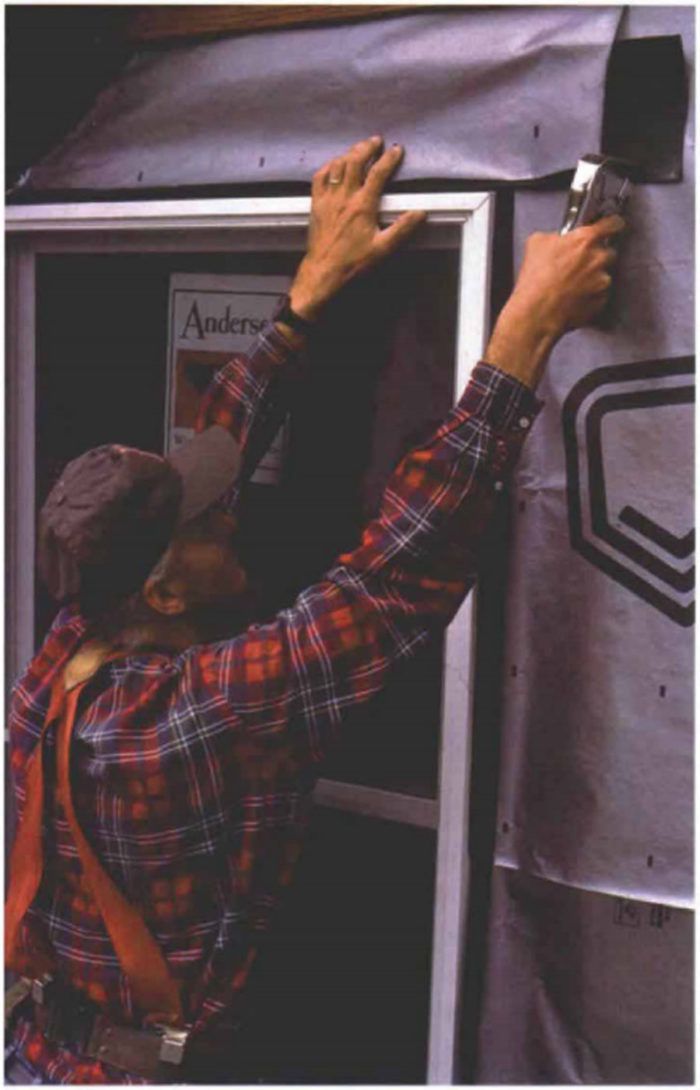

Keeping water moving out and down is the key to effective sidewall flashing.

Synopsis: This article explains the materials and methods used to prevent water from penetrating the exterior cladding of a structure, particularly around key entry points. The author discusses materials and tools typically used and then explains the various flashing applications, moving from the mudsill up the wall to the roof.

As a carpenter for over 20 years, I’ve seen the mischief water can do when it gets under a building’s skin. I’ve also studied ways to prevent this situation from happening. What I’ve learned is that water can be coaxed and persuaded to remain on the outside of a building, where it belongs, if you know the right methods and use the right materials. Although these methods and materials are similar for sidewall and roof flashings, this article will look specifically at flashing the various sidewall trouble spots.

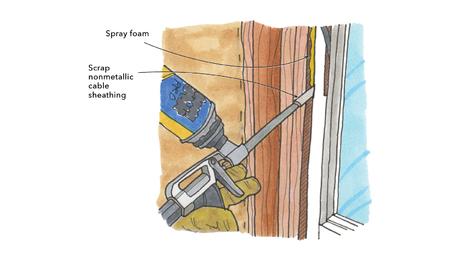

Flashings are membranes woven into a structure’s exterior cladding at key points to keep water moving out and down. They work primarily by means of gravity. The underlying principle, therefore, in all flashing, siding and roofing work is that which is above overlaps that which is below. In addition, well-designed flashing should break the surface tension of water, which will help prevent moisture migration along cracks and between materials.

Copper and lead are traditional choices

Metal has long been used for flashing because it can be beaten or rolled into thin sheets. Copper in particular has been a popular choice because of its excellent corrosion resistance, even in the presence of an alkaline material such as concrete. It is also strong enough to hold a shape yet soft enough to work easily. Finally, copper can be easily and permanently joined by soldering. This trait makes it possible to fabricate complex, watertight shapes that can’t be made by means of bending alone, which is particularly important in roof flashing. Copper for flashing is usually sold in a 16-oz. weight (1 sq. ft. weighs 16 oz.) and is available in soft and hard tempers. Hard, or cold-rolled, copper is stronger and is preferred for most flashing work.

Copper is often used for its traditional appearance, and as it weathers, it develops an attractive, protective surface, or patina. Lead-coated copper has even better corrosion resistance than plain copper, with a price tag to match, and is used primarily in urban environments where air pollution can corrode plain copper prematurely.

Despite its advantages, however, copper does have a few drawbacks. Runoff from plain copper can sometimes cause a greenish staining, although this problem does not occur with lead-coated copper. Another problem is the incompatibility of copper and cedar: The extractives from red-cedar shingles and shakes will deteriorate copper and, therefore, make it a poor choice where red cedar is present. Copper’s main disadvantage is price; its cost is three to four times that of aluminium.

Like copper, lead has a centuries long tradition as a flashing material. It has good corrosion resistance and is highly malleable. It’s still used occasionally for custom work where a flashing must be bent to conform to an irregular surface, such as a tile roof. On the downside, lead’s softness makes it vulnerable to punctures, and its low melting point makes it difficult to solder; the lead sheet will melt as readily as the solder.

For more photos and information on flashing walls, click the View PDF button below.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

BOSCH Compact Router (PR20)

Reliable Crimp Connectors

Large-Capacity Lightweight Miter Saw