Adding a Seasonal Porch

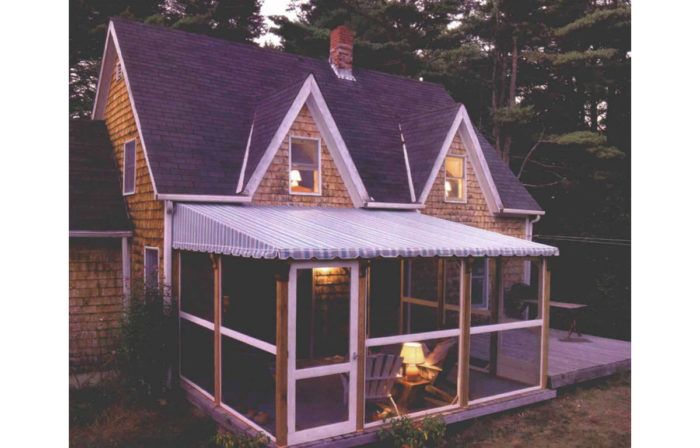

A timber-framed, screened-in porch with an awning roof keeps out insects but comes down easily to let in winter sun.

Synopsis: This article describes an unusual timber-frame screen porch that keeps out insects during the summer but can be dismantled in the winter to give the house a warming sun exposure. The awning roof and timber-frame sections are light enough to handle easily.

In an age of maintenance-free building, a structure that requires attention at least twice a year may seem out of step. But as I look back, my decision to convert an open deck into a summers-only screened-in porch still makes sense to me.

From the outset, you must believe that it actually gets hot in Maine during the summer. We live in a small clearing in the woods, sheltered by lots of tall, wind-shielding pines. On sunny days, the temperature on our open, south facing deck regularly reaches well into the 90s, frequently topping 100°F or more.

Of course, by late afternoon it usually cools to the 60s. Unfortunately, the drop in temperature brings out mosquitoes that sometimes are difficult to distinguish from seagulls. In the evening, sorties of moths and formations of deerflies are chased by battalions of bats, ensuring that an open deck remains relatively unusable.

Then there’s winter in Maine. It gets cold here. Very cold. To help with heating costs, you need all of the south-facing windows you can get. So shading those windows with a permanent roof over a screened-in porch that’s only useful three months out of the year is counterproductive. Besides, such a roof would create a gloomy, sunless living room, which in my house is the south facing room adjacent to the deck. So the idea of a seasonal screened-in porch was born.

Choosing the right type of beams was the critical first step

I couldn’t find a design for such a porch in any architecture book, so I fell back on my own building knowledge, particularly my post-and-beam background and some of my boat-building experience.

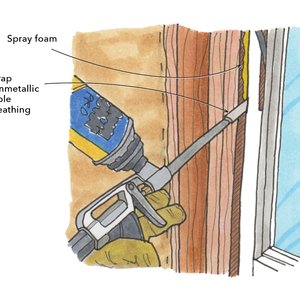

The post-and-beam approach seemed the best way to achieve the required basic strength without a lot of studs to clutter the view. A minimum of framing members also would simplify assembly and disassembly. Because the load on these posts and beams would be no more than the weight of the galvanized steel-tubing awning frame and the awning itself, 4×4 top plates and posts would be more than sufficient.

Still, I had to keep everything lightweight for easy assembly and disassembly by one person. I also knew that posts would absorb rainwater along their bottom edges like sponges. So the post-and-beam structure would also have to be highly rot-resistant. These requirements forced me to rule out pressure-treated pine. Although available and inexpensive, it’s too heavy and prone to movement during the humidity swings common during summers on the Maine coast.

The need for a light, durable wood led me to cedar. I could’ve used local northern white cedar, but I settled on western red cedar as the best solution. It’s more straight-grained than local cedar, and clear 4x4s are readily available in lengths up to 20 ft. California redwood also was a possibility, but it’s slightly more expensive than western red cedar and would have taken longer to get delivered.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below: