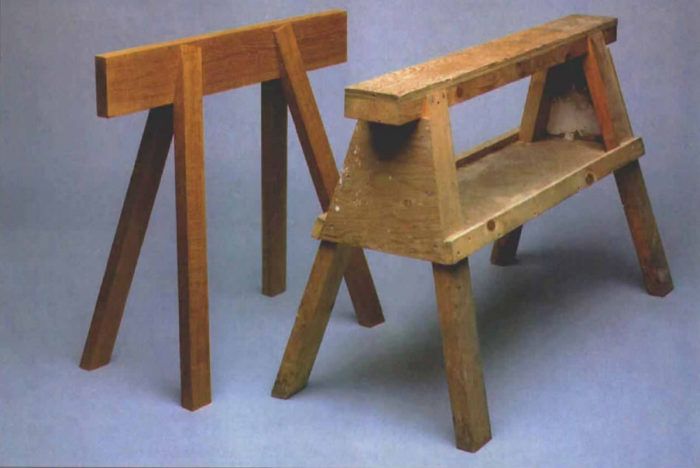

Sawhorse Roundup

A selection of new and traditional designs for sawhorses that are easy to build, strong and lightweight.

Synopsis: A survey of variations on the basic sawhorse, including specialized or unique designs from veteran carpenters such as Larry Haun and Jim Tolpin. Also included are designs for folding and knockdown sawhorses. Some can be built in just a few minutes.

You can tell a lot about a carpenter by his sawhorses. Having said that, let me confess that I own a set of sawhorses that is falling apart. Inherited along with the first “fixer-upper” house I ever bought, they wobble like drunken cowboys, the legs have been shortened more than once to get rid of rot, and I’m constantly pounding their loose nails back into place. I’m reluctant to toss them because they’re still useful, despite the abuse and neglect that have been heaped on them over the years. Sometimes sawhorses just don’t get treated very well. I’ve seen horses holding up a load of 3/4-in. plywood with a 250-lb. carpenter wielding a worm-drive saw on top. I’ve watched them in the rear view mirror of my truck, bouncing on the highway as I drove away at 55 mph. I’ve seen them cut almost clean through by carpenters who don’t realize that the blade in a circular saw can be raised and lowered.

Part of the beauty of sawhorses is that they are pretty easy to build out of materials that are readily at hand. Of course, metal sawhorse brackets that quickly clamp onto 2x lumber are also available, but these brackets don’t make sawhorses I’d want to stand on. And having to buy a part for a sawhorse is a real psychological barrier for most carpenters. That is why many of the sawhorse designs I’ve seen rely on the flotsam and jetsam normally found on a job site odd lengths and sizes of lumber, scrap plywood, spare joist hangers and connectors, and assorted screws and nails. The editorial staff here at Fine Homebuilding thought that it was time to bring together the best of these designs: some of them previously published in the magazine, some of them from other sources and some of them brand new.

A good sawhorse is strong and light

Everyone has heard the story of the new man on the job site who is asked to build a pair of sawhorses. If he can turn out a serviceable set in a reasonable amount of time, he gets hired; if not, he hits the road. Personally, I’ve never met any carpenter who has had to take this kind of entrance exam, but it makes sense: Building a sawhorse is a good measure of a carpenter’s ability to think in three dimensions; understand (at least intuitively) trigonometry; and accurately measure, cut and assemble lumber.

Obviously, the first task of a good set of horses is simply to stand up, sometimes under surprisingly heavy loads. Strength is just one variable in the design equation, though. Often, the same set of horses that held the big stack of 20-ft. long 2×12 lumber for framing rafters early in the job will be brought inside later and be used to hold trim for painting.

So sawhorses have to be strong, relatively lightweight and relatively easy to move around. Because most carpenters don’t have specialized sawhorses for specialized tasks, the best sawhorse designs juggle strength, light weight and portability. Of course, the more engineering required to achieve a high strength-to-weight ratio, the more complicated and labor-intensive the construction can become.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below: