Building an Arts and Crafts Stair

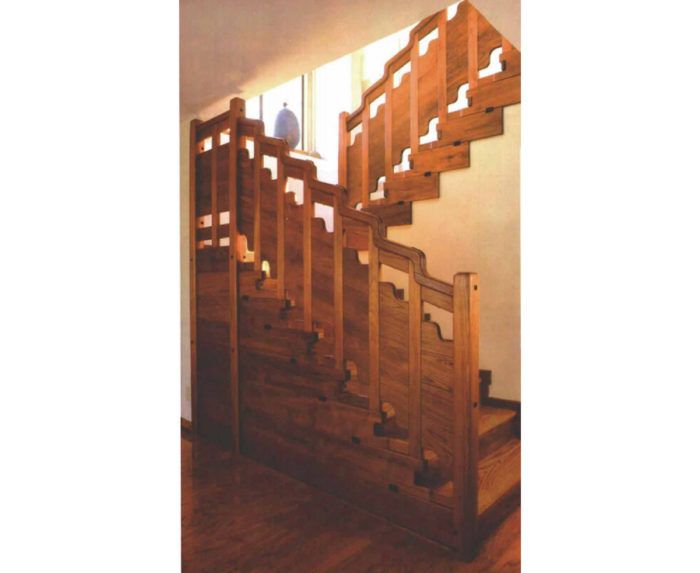

An updated and code-compliant interpretation of the classic Greene and Greene Gamble House staircase.

Synopsis: Stairbuilder Lon Schleining faced considerable stylistic and technical challenges in building a reproduction Greene and Greene stairway. Because the Gamble House stair on which this reproduction is modeled doesn’t meet present-day building codes, Schleining researched and redesigned the stair, attempting to remain true to the Arts and Crafts tradition while building a code-compliant staircase. This article tells how he did it.

Although the fame and the reputation of Charles and Henry Greene are well-deserved, another pair of brothers had a lot to do with their success. Peter and John Hall, along with their crew, were responsible for building much of what the Greene brothers designed. Interestingly to me, Peter Hall was also a stairbuilder, and together, the Greenes and the Halls created the masterpiece that is the staircase at the Gamble House.

A classic Greene and Greene Craftsman-style bungalow, the Gamble House is in Pasadena, California, not far from where I live. The house, built in 1908 and now a National Historic Landmark, has exquisite joinery and furniture that have inspired countless woodworkers over the years, me included. So I was pleased when fellow Greene and Greene aficionados Carl and Hannah Schafer commissioned me to build an updated interpretation of the Gamble House staircase in their own home in Long Beach.

My goal was to build a stair that would capture the spirit of the original and also meet building codes. Although I’ve built some 300 staircases since 1978, this one would prove to be the most challenging.

First, comply with building codes

The Gamble House staircase is a real puzzle. Vertical and horizontal members of different thicknesses intersect from several directions, forming an intricate sculpture of teak, oak, and ebony. Beautiful as it is, though, the stair doesn’t comply with current building codes because its handrail exceeds the 2-in. maximum width, and its undulations take it below 34 in. in places. The balustrade also has openings that are too large.

To oversimplify my design process a bit, I usually begin with what I have to do, then work toward what I want to do. What I had to do was comply with code. What I wanted to do was to capture as many of the subtle details in the original stair as possible. I was going to have to figure out a way to keep the waterfall look of the handrail without stepping outside that 34-in. to 38-in. height range. In addition, I would have to design the stair panels so that the largest opening would still be smaller than a 4-in. sphere.

At my shop, I have a large drawing table where I draw all of my staircases, a procedure that I’ve followed for many years. I encounter a lot of twists and turns in the course of building staircases, and I find that drawing full scale is the easiest and fastest way for me to work out tricky designs. Once finished, the drawings show me some of the hurdles I have to get past to make the project work, and I can lay the parts right on the paper to verify angles and sizes. I don’t have to dimension anything because I can measure right off the drawing.

RELATED DRAWINGS

- Stairs: Code, Craft, & Design

- 2 Rules for Building Comfortable Stairs

- Safety Regulations for Irregular Stairs

For more photos and details, click the View PDF button below: