Fixing a Cold, Drafty House

Forget about weatherstripping doors and windows. Sealing and insulating the attic are the keys to lower heating bills and a more comfortable house.

Synopsis: Weatherization specialist Fred Lugano takes a comprehensive approach to attacking insulation and moisture problems. While the materials and methods that he advocates are applicable to new construction as well, this article examines the procedures, special equipment, and materials that he uses to weatherize an old house. Of particular interest are his use of dense-pack cellulose as an insulation material and pressure diagnostics based on blower-door directed air sealing.

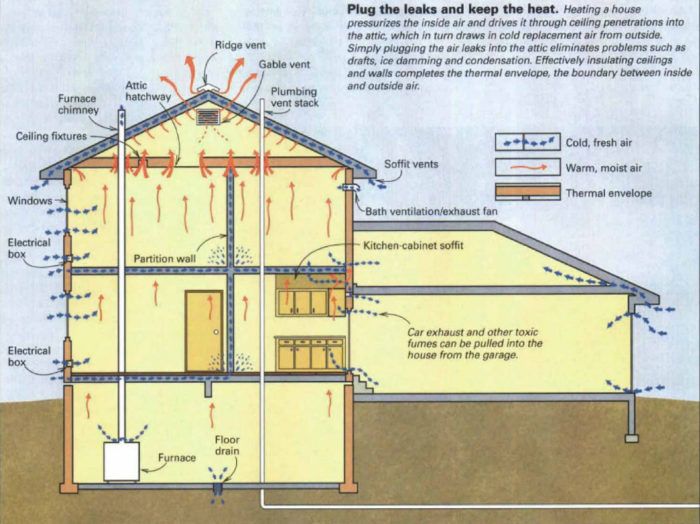

As a weatherization contractor, I meet a lot of people who are sick and tired of cold, drafty houses. Their problem—and maybe yours, too— is that they live in homes that don’t work very well. These houses, new and old, cost too much to heat and to cool. Their paint peels, their roofs dam with ice, and they sometimes make their owners sick. Simply put, these homes lack a good thermal envelope, or an insulated, air resistant boundary between conditioned inside air and outside air.

Incomplete thermal envelopes are common in old houses, but new ones can have the same or similar problems. Open-web joist systems, cantilevers, balloon-frame walls and mechanical penetrations allow outside air to penetrate buildings. Sometimes the problem is poorly installed insulation with too many voids, but more often, holes in the building are the real culprits.

Caulks and weatherstripping can help plug small holes, but this is like using Band-Aids to treat major wounds. The total area of the holes I’m talking about is measured in square feet, not in square inches. Even so, these problems can now be fixed simply and economically, and buildings a century old can be routinely upgraded to higher performance levels than typical new homes. And the principles and methods are applicable to new construction.

Air movement in floors, walls and ceilings is bad

Air infiltration is the predominant heatloss mechanism for most buildings, so the primary goal of any weatherization effort should be to control air infiltration. Not all infiltration is bad; humans, pets, and furnaces and other combustion devices need a continuous supply of fresh outside air, and the air in most homes should be replaced (either naturally or mechanically) about six to eight times per day.

But relying on a home’s air leaks is not a good way to provide fresh air. I’ve worked on buildings that have suffered as many as 30 air changes per day. At that rate, the conditioned air doesn’t hang around long enough for the house’s insulation to have much of an effect on keeping it in.

Air infiltration forces warm, moisture-laden air into cold, dry places. The buoyant nature of hot air drives it into every ceiling penetration, and if there are large holes, the house acts like a giant chimney, pulling cold fresh air in from below, heating it and pouring it into the attic. Loose attic hatches, large cutouts for plumbing vents, exposed beams and recessed lights are perfect “chimney flues” for these air currents.

For more photos and details on fixing drafts, click the View PDF button below.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Great Stuff Foam Cleaner

Loctite Foamboard Adhesive

Insulation Knife