How to Avoid Common Flashing Errors

Building paper and adhesive-backed bituminous tape are vital ingredients in protecting a building from water damage.

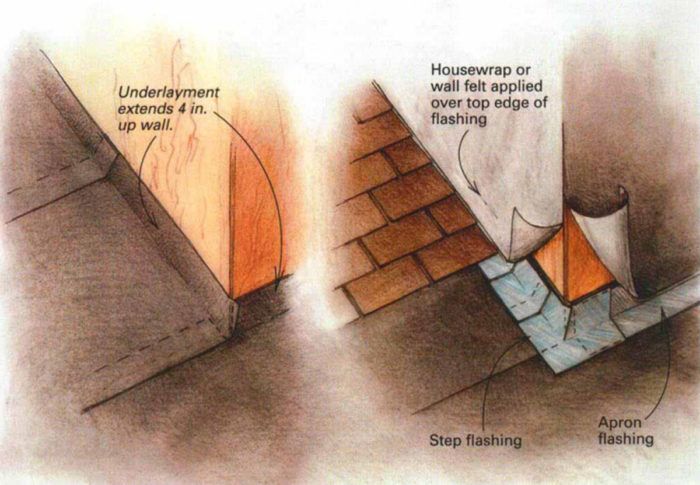

Synopsis: Improperly applied flashing can lead to rot and even structural problems. This article, written by an architect and building consultant, explains how flashing should be applied around windows, deck ledgers, and cheek walls, and along rakes.

To understand flashing, try thinking about a house as essentially a tent with architectural embellishments. You’ll know what I mean if you’ve ever been camping in the rain and inadvertently zipped up the door flap so that the bottom edge turned inward. The big puddle inside the tent, the one that soaked your last dry shirt, was a flashing problem not unlike those you can build into a house if you’re not careful.

Flashing is one of the smallest parts of a building, so it sometimes doesn’t get the respect it deserves. But it sure will exact its revenge when it is overlooked or improperly integrated with other building elements. I see a lot of that. For the past seven years, I’ve worked as an architectural consultant, and I’ve poked into many moisture-damaged houses whose troubles started with improperly applied flashing.

Water is a wily enemy. Driven by wind or sucked into crevices by negative air pressure inside the house, it can flow uphill between construction layers. Once inside, water will subject building materials to alternating spells of soaking and drying until first the paint and finally the wood just give up.

Flashing to me is more than metal. In a general sense, flashing refers to a configuration of materials that are arranged to direct water to the exterior. The materials could be metal, asphalt-impregnated building paper (felt) or, more recently, adhesive-backed bituminous tape. Together, these materials work to ensure that corners, openings, and edges will exclude water. The wall tape is an important ingredient. It’s a modified bituminous material on a backer of cross-laminated polyethylene with an aggressive adhesive. It’s sold by several companies. Building felt, housewrap, and bituminous tape are part of what the Uniform Building Code calls a “weather-resistive barrier,” the final barrier to water penetration.

Flashing should be applied so that water flows to the exterior rather than being trapped behind one of the building’s construction layers. If the correct installation of flashing could be boiled down to a single phrase, it would be this: Don’t leave any edges looking uphill. This underlying principle is about as basic as placing the shower curtain on the inside of the tub before you turn on the water. In my dealings with problem flashing installations, I’ve found four situations where mistakes commonly occur: around vinyl-clad and aluminum-clad windows manufactured with nailing flanges, at the intersection of a roof and a sidewall (a dormer, for example), where an outside deck intersects the sidewall of a house, and, finally, at the edge of a roof. Correctly flashing these spots won’t take much more time than doing it wrong, and the effort will save you lots of heartache.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Jigsaw

Metal Connector Nailer

N95 Respirator