Updating the New England Shingle Style

A steep roof gives the exterior an angular, dramatic shape; traditional materials keep the house grounded

From a windy point of land in Stonington, Connecticut, you can look across the mouth of Little Narragansett Bay and see Watch Hill, Rhode Island, home to some grand examples of New England shingle-style houses. Starting in the late 1880s, summer communities along the Connecticut and Rhode Island shore developed their own style of dormered cottages with shingled porches. Summer estates of Watch Hill transformed both Georgian and Palladian architecture into a shingle style embellished with classical details.

Because of this rich architectural tradition, a shingle-style house seemed a natural choice when my wife and I built on a 4-acre parcel in Stonington. Kathy and I wanted more than a place to live. Like many architects who specialize in residential design, I faced the challenge of building a house that could be shown to discriminating clients while addressing the very practical requirements of a growing family.

Our house borrows a number of familiar shingle-style themes, from a cedar-clad exterior to a large, steeply pitched roof. But our construction budget was tight. We were careful not to design beyond what the real-estate market would support. Our 3,400-sq. ft. Floor plan included features we knew would have a high resale value while making the house comfortable and inviting.

An open floor plan

A kitchen and dining room divided by an island countertop keeps the first floor from feeling cramped, and it encourages plenty of interaction when the author and his wife entertain guests. A zero-clearance fireplace paneled in cherry, with built-in wood storage, separates the living room from the dining area.

Exterior shapes and materials honor an old regional style

The shingle-style house is truly an American creation. Inventive, organic and delightful, shingle-style houses often present us with porches, loggias and arcades that create outdoor rooms. What may be most remarkable about the style is how it uses volume and space. The main parts of these houses often were designed under massive gable or gambrel roofs, with porches sculpted out of the main volume rather than added to it. Interior spaces and features often were reflected outside in the form of decorated bays, bump-outs, towers and chimneys. And, of course, most surfaces were covered in cedar, whose skinlike quality gives rise to a rich variety of surface textures.

We incorporated all these features in our design. We started with the basic shape—a heavy attic volume sitting on a base. A very steep pitch on the main roof (18-in-12) allowed us to get the most possible floor space with a minimum of exterior wall. For the attached garage, a 14-in-12 pitch on the roof gave us 400 sq. ft. of additional attic space for possible expansion.

The triangular second-story and third-story volume is really a truss in section, so I could use 26-ft. long 2×8 rafters instead of deeper framing material. I was also able to use balloon-framing, which saved some money and led to an interesting interior detail (for more, see Balloon-framing saves time and money).

The roof, end gables and dormers are clad in a lightly stained red cedar. All walls are clad in a clear, finished white cedar. This two-tone palette emphasizes the visual weight of the roof and gives the base of the house a pedestal-like quality. Exterior trim is clear-finished red cedar that we let weather right along with the siding, and the tongue-and-groove red-cedar soffits required no vent openings (for more, see Venting a roof at the rake).

Balloon-framing saves time and money

Old-style balloon-framing makes use of long studs that rise all the way from the sill to the roof plate. At one time, this method was the typical way of framing a house. With fewer framing members to cut and assemble, balloon-framing is economical. And because studs are continuous, balloon-framing also offers some structural advantages.

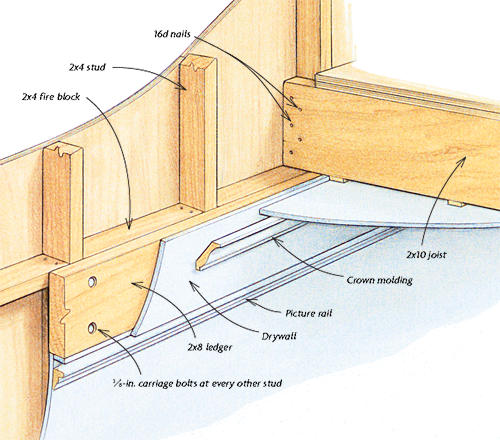

In platform-framing, which is now standard for stick-built houses, second-floor joists are supported by a double top plate at the first floor. In balloon-framing, framers typically cut notches in the studs and let in a ledger or ribbon piece of 1x material. I liked the idea of balloon-framing for at least two reasons: Balloon-framing resists the lateral forces exerted on the walls by the roof better than a kneewall; and the framers found it simpler. But instead of notching studs, I through-bolted a 2×8 ledger to the studs to carry the ends of the second-floor joists. I used a pair of 3/8-in. carriage bolts, countersunk on the outside of the building, at every other stud. In between, the ledger is nailed. In addition, the 2×10 joists are fastened to the studs with 16d nails.

While supporting the second floor, the ledger also created an interesting interior detail. I wrapped the ledger in 1/2-in. drywall and capped it with crown molding. Builders who have dropped by to see the house say that’s one detail that they are sure to pick up. But don’t forget to add fire blocks; one disadvantage of balloon-framing is that without the blocks, fire can spread between floors much more easily. The fire blocks should be installed in each stud bay.

Venting a roof at the rake

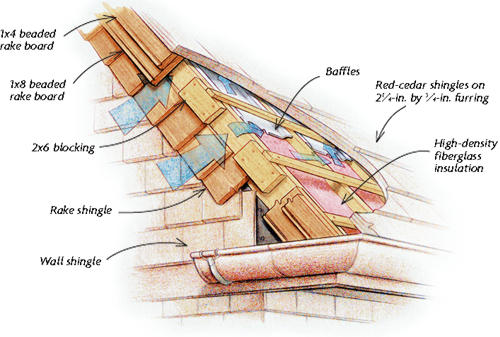

Continuous aluminum soffit vents coupled with a ridge vent are now the norm for venting a roof. But not the look I wanted. Even so, a cedar roof needs to breathe. A solution devised by the builder, Joe Stanton, was to allow air to enter the roof at the rake edge, giving the house a much cleaner look.

Red-cedar roof shingles are applied to furring strips nailed to the rafters 5-1/2 in. o. c., leaving gaps between the boards. Unlike a roof sheeted over with plywood, a skip-sheathed roof allows good air circulation on the underside of the shingles. At the rake edges, a band of shingles applied parallel to the roof edge is capped by two cedar trim boards. Air enters through the many small gaps created when straight trim is laid over tapered shingles. High-density fiberglass insulation in the roof is held away from the furring by molded plastic baffles.

An open floor plan on the first floor makes a social living area

Instead of carving up the first floor into separate rooms, we opted for connected living, dining and kitchen spaces. When we entertain, guests move naturally through the three spaces, and the long counter island between kitchen and dining area becomes a buffet. Living and dining areas are separated by a freestanding fireplace hearth. By opting for a two-sided, zero-clearance firebox as opposed to masonry construction, we saved enough money to use cherry paneling at the kitchen island and fireplace enclosure. The living room, separated from the dining area by the fireplace, is accessible without being smack in the middle of traffic

.

We added a brick patio surrounded by a low stone and slate wall on one side of the living room. Capped by a trellis of western red cedar and accessible through a pair of French doors, the patio makes a pleasant extension of the living and dining areas.

A kitchen is an easy place to spend a lot of money, so we looked for ways to keep costs down. We found a set of cherry cabinets with a granite countertop at a showroom liquidation. We sprayed the paint-grade lower cabinets on site in a rich hunter green and added a long butcher-block counter along one wall. The resulting kitchen cabinetry is economical, but it gets vitality from being eclectic. Floors are finished in a rough, earthy Italian tile, and the glazed green tile backsplash is accented with hand-painted tiles from Deruta, Italy. With all the open space beyond the kitchen, it made sense to add a more intimate breakfast nook off one end of the kitchen. This space has its own access to the outside.

A built-in fan keeps the second and third floors cool in summer

Second-floor bedrooms are on each end of the house, where gable walls allow for plenty of windows. In the master bedroom, the 15-ft. ceiling goes right to the ridge, and a bank of east-facing windows adds both light and ventilation. Although we put in two gable dormers in this high ceiling, I kept dormers elsewhere on the second and third floors to a minimum. Indiscriminate or decorative use of dor-mers would have inflated construction costs dramatically and undermined the simplicity of the structure. A third-floor space, accessible by a circular stair we have yet to install, overlooks the master bedroom and will make a good office space when it is finished.

The house is naturally air-conditioned by cool air from the surrounding woods. Ceilings on the first floor are 9 ft.; they vary from 10 ft. to 15 ft. on the second floor. For super-hot weather, we have a 2,000 cfm fan installed in the side of the chimney chase. With intakes at the third-floor level, this thermostatically activated fan will exhaust hot, stratified air and pull cooler air up through the stairwell from the first floor. This approach saved us a lot of money when compared with a much more elaborate central-air system. The chase also was a good place to put plumbing vents, keeping roof penetrations to a minimum.