All About Rain Gutters

Whether aluminum, copper, steel or plastic, gutters need good design and proper installation to put roof runoff where it belongs.

Synopsis: Getting rain gutters to work properly amounts to more than slapping them up on roof eaves and hoping for the best. The author lists pros and cons of various gutter materials, offers a guide to choosing the right size and shape and explains how they should be attached so they perform as intended.

You’ve probably cursed your gutters more than blessed them. Purposeful yet troublesome, gutters are conspicuous as architectural afterthoughts on the otherwise carefully designed facades of many houses. Gutters clog with composting leaves, and in my neighborhood, they often sprout thickets of maple seedlings. In the north country, gutters that are half-torn from the house by sliding snow predict spring’s arrival more accurately than does any groundhog.

Despite their shortcomings, gutters are essential to the longevity of most homes. Without gutters and downspouts leading rainwater away from the house, foundations become feedlots for mold that can sicken your family and rot your house. Wet foundations lead to peeling paint and even to damp attics.

Unless the soil that is surrounding your house is free-draining gravel that never saturates or unless you live where rain is only a Christmas-tree decoration, your house needs gutters. Here’s how to make the best of them.

There’s more to choose from than seamless aluminum

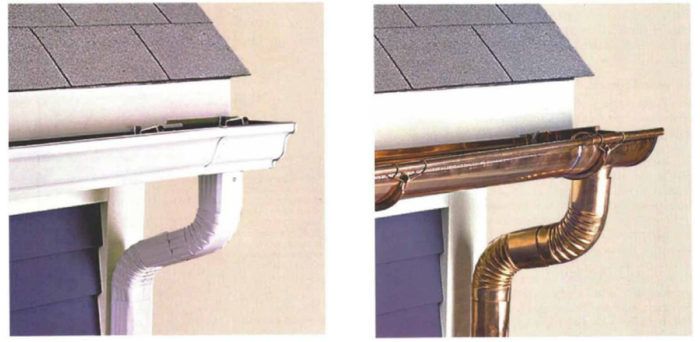

One of the first choices you’ll have to make is what material and profile your gutters should be. The most common materials are aluminum, copper, galvanized steel and plastic. The Architectural Sheet Metal Manual (Sheet Metal and Air Conditioning Contractors National Association Inc./SMACNA) lists over a dozen standard profiles. (At $176, this book is pricey, but it shows every flashing and sheet-metal detail imaginable.)

The most common gutter in use nationally is 5-in. aluminum K-style. K-style gutters are called by that name simply because the profile’s place in SMACNA’s alphabetical hierarchy is the eleventh letter of our alphabet. The seamless-gutter contractors that I know produce miles of this rectangular-back, ogee-front gutter every year.

Seamless gutters are the least likely to leak. Specialized truck-mounted or trailer-mounted forming machines pull flat metal stock from a coil and shape gutters of the desired profile on site. One-piece lengths as long as the stock on the coil are possible, but thermal expansion and contraction limit the practical length to about 50 ft. These forming machines are costly, and contractors are likely to be able to produce only 5-in. and maybe 6-in. K-style.

Of course, lumberyards and specialty wholesalers sell these and other profiles already formed, but their lengths are usually limited to 10-ft. or 20-ft. sections that must be joined on site.

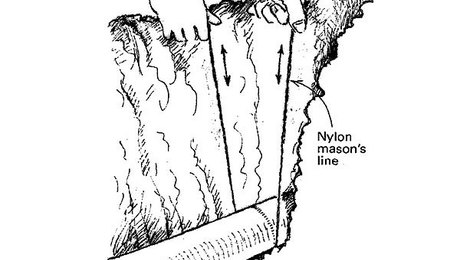

The problem with joining gutter sections is that joints are leak-prone. On metals that can be soldered, copper or galvanized steel, the sections must overlap by 1 in. and be riveted on 2-in. centers before soldering. Aluminum and painted steel can’t be soldered. Their 1-in. lap must be sealed with paint-compatible gutter sealant or highgrade silicone caulk and riveted on 1-in. centers.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Graphic Guide to Frame Construction

A House Needs to Breathe...Or Does It?: An Introduction to Building Science

Get Your House Right: Architectural Elements to Use & Avoid