Q:

In recent Q&A items, Mark Eatherton has addressed the issue of venting high-efficiency boilers into masonry chimneys. But I’ve noticed that when a gas furnace in my area is being replaced with a standard-efficiency furnace, a flexible aluminum tube is inserted into the masonry-lined chimney as a liner. I assume that this aluminum liner is to prevent damage to conventional chimneys. Can it be used for all standard-efficiency gas appliances, and should it be used for other gas appliances, such as gas fire logs that are installed in existing fireplaces?

Tom Kadesch, Damascus, MD

A:

Mark Eatherton, a plumbing and heating contractor in Denver, Colorado, replies: Newer furnaces and boilers are generally more efficient than the units they are replacing, meaning that there is less residual heat left in the flue gases of the new appliance to maintain good draft action in the chimney. Consequently, the flue gases cool to below the dew point before exiting the chimney, and highly acidic moisture condenses inside the chimney. As I mentioned in Venting high-efficiency boilers into masonry chimneys, this acidic condensate dissolves the mortar lining of the chimney, so the chimney should be lined with an acid-resistant flue liner.

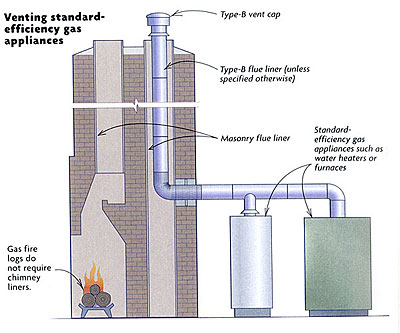

These liners help flue gases to maintain a higher temperature to increase draft and to minimize acidic condensation. The appliance must be compatible with the liner it’s connected to. Most standard-efficiency gas-fired appliances that are 84% spontaneously efficient or less can be attached to a flexible-aluminum flue liner or a type-B liner (standard galvanized-steel double-wall vent pipe). The flexible-aluminum liner is usually used in chimneys with offset flues that aren’t straight. Gas appliances such as condensing boilers that are more than 84% efficient may require special liners to deal with their acidic condensate.

Local codes or the appliance manufacturers’ instructions must be followed to the letter when retrofitting a newer appliance into an existing dwelling, regardless of whether the existing chimney is metal or masonry. The liner must run the full length of the chimney and be capped with a type-B vent cap on top of the chimney. And don’t forget that for combustion, you need to introduce outside air into the mechanical room.

Gas fire logs are a different beast. Firelog flames are typically set much richer to maintain the appearance of a flickering log fire. If the burn were as clean as, say, a furnace or a boiler, the fire log would have all the ambiance you’d get from sitting in front of your oven and staring at the burner—not my idea of what a fireplace should look like. In fact, most open-hearth gas logs burn so inefficiently that they produce substantial amounts of carbon buildup, requiring that the chimney be both inspected and cleaned regularly.

In most cases, there is plenty of residual heat left in the typical open-hearth gas log to maintain adequate draft conditions in the chimney and to avoid flue-gas condensation without a flue liner. Exceptions to this situation are a chimney with a flue passage that is too big or a chimney exposed to the outside on two or three sides. In these cases, a flue liner is recommended to help prevent the flue gases from cooling and forming acidic condensate.