Building Dry Stone Walls

A systematic approach to stone-wall building saves time and turns beginners into artists.

Synopsis: A dry-laid stone wall is a work of art, and it will last for generations if built properly. The author explains how it’s done, from the first course of big rock to finished height. A useful sidebar explains how to split stone cleanly.

You could consider stonework a dying art form or just dismiss it as “stacking stones.” In New England, it’s a little of each. In the span of a few hundred years, thousands of these stone walls were created—not by masons, but by settlers who needed to know a little bit about everything to survive. As they cleared land, they unearthed stones that could be used to retain soil, build foundations, and mark land boundaries. Today, the region gets a good deal of charm from stone walls that embrace the landscape and embellish old structures.

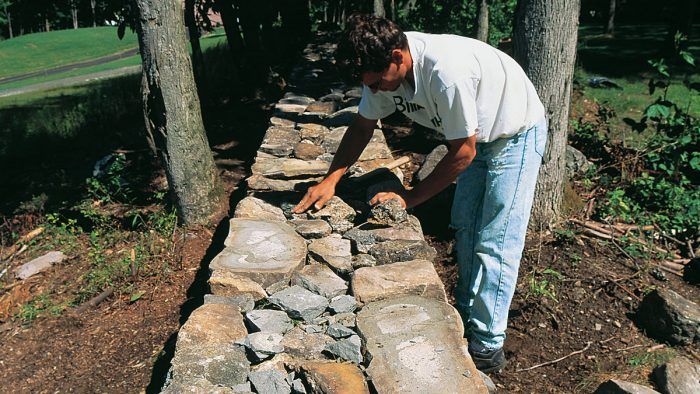

Building stone walls is physically demanding. Yet I find few labors give me as much creative satisfaction as finishing a mortarless, or dry, wall. It doesn’t take inherent artistic ability to build a wall. It’s not rocket science. You don’t even have to be Italian. A fairly strong back, a few inexpensive tools, and a pile of stone are all you need. Add to this a system of simple, steadfast rules and a little practice, and you’ll be well on your way to building structures that will outlive your children.

I prefer dry stone walls over mortared walls for a number of reasons. Water flows right through dry-laid retaining walls, so it doesn’t pond and cause problems. Dry walls are cheaper, and the footing does not have to be solid concrete. If a dry wall moves or part of it falls, repairs are easy and undetectable. With no mortar to mix, you will spend a lot less time per work session on startup and cleanup chores. Finally, if you can tackle a freestanding dry wall, then building one with mortar is only a small adjustment. The opposite is not necessarily true.

Walls can be a mix of fieldstone and blasted stone

I use both fieldstone and blasted stone, often in the same wall. When I use fieldstone, I do little cutting but try to use the natural contours of the stone whenever possible. Even if the face of such a wall is imperfect, it has a lot of character. I often have to supplement supplies of natural fieldstone with blasted stone, as I did in rebuilding the wall featured here. Blasted rock is often easier to cut, split, and shape. It comes in slabs, so it’s easier to work with. Either way, stone is not cheap. Stone can cost from $50 to $250 per ton (there are about 1½ tons per cu. yd.). In the wall that I built in the photos featured in this article, I used fieldstone that was already on site, and then ordered a few pallets of blasted stone to augment it. A 3-ft.-high wall would require a yard of stone per 3 ft. of length. This plan allows for extra stone.

There should be plenty of Yellow Pages listings for stone in your area. If you are lucky enough to have a quarry nearby or a farm that is selling old walls, you can cut out the middleman and save some money. If you have stone at the site, you can go to a stone yard and try to match it. However you do it, always get a little extra. In that case, you won’t have to pay a delivery charge for just a little bit if you run short. You can also save money by using bricks, broken flagstone or concrete as the filler inside the wall; it won’t show when you are done.

Walls can be a mix of fieldstone and blasted stone

I use both fieldstone and blasted stone, often in the same wall. When I use fieldstone, I do little cutting but try to use the natural contours of the stone whenever possible. Even if the face of such a wall is imperfect, it has a lot of character. I often have to supplement supplies of natural fieldstone with blasted stone, as I did in rebuilding the wall featured here. Blasted rock is often easier to cut, split and shape. It comes in slabs, so it’s easier to work with. Either way, stone is not cheap.

Stone can cost from $50 to $250 per ton (there are about 11/2 tons per cu. yd.). In the wall that I built in the photos featured here, I used fieldstone that was already on site, and then ordered a few pallets of blasted stone to augment it. A 3-ft. high wall would require a yard of stone per 3 ft. of length. This plan allows for extra stone.

There should be plenty of Yellow Pages listings for stone in your area. If you are lucky enough to have a quarry nearby or a farm that is selling old walls, you can cut out the middleman and save some money. If you have stone at the site, you can go to a stone yard and try to match it. However you do it, always get a little extra. In that case, you won’t have to pay a delivery charge for just a little bit if you run short. You can also save money by using bricks, broken flagstone or concrete as the filler inside the wall; it won’t show when you are done.

Chris Kachur is a stonemason who lives in Southbury, Connecticut. Photos by Scott Gibson.

From Fine Homebuilding #126