A Balustrade of Branches

Wood drawn from the forest makes a functional work of art.

Synopsis: Arizona carpenter Dan Davis tried something new when he built a staircase for a client who wanted a unique look: a handrail made of alligator juniper in its natural state. This is a brief description of how he made the balustrade.

I had just finished building a conventional over-the-post balustrade with manufactured stair parts when Pete Giovali called. He, too, wanted a new staircase and handrail. But Pete has a taste for the unusual, and his new staircase and balustrade would be anything but out-of-the catalog ordinary.

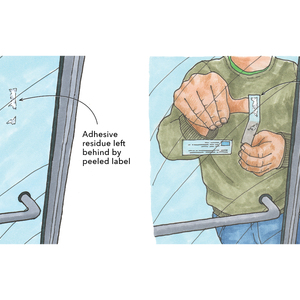

I planned to use traditional construction methods, but my source of materials for this balustrade was private forest land near Flagstaff, Arizona. I scoured stands of alligator juniper, which grows in gnarled, twisting forms, looking for branches that could be used for newels and balusters, and 90° bends for corners and easings. I also looked for long, straight, slim branches for the 8-ft., 10-ft. and 11 ft. rail sections. In the end, I milled the long rail pieces from Arizona cypress. Shorter rails on the staircase could be made from juniper. Once in the shop, I used a draw knife to peel the bark. A disk grinder did the heavy work, and I finished with a palm sander and sanding my hand.

Fitting pieces requires patience, persistence and time

I imagined the dwarves’ staircase in the Disney movie Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, with a dreamy look of newels growing through balconies. To create it, I had to invent some techniques and devote plenty of time-in all, the stair project took 1,500 hours, although not all of that was devoted to the balustrade.

With the new oak staircase built, the newel posts were the first pieces of the balustrade to go in. They all had to be scribed to fit. I held each piece in place for marking with scraps clamped to the nosings and the bottom end resting on a ladder or sawhorse. I wanted the nosings to die into the newels, but getting this fit exact was difficult. I scribed cutlines into the newel, then used a small chainsaw to make the rough cuts. A disk grinder and chisels cleaned up the cuts, and I fine-tuned the joints with files, chisels and a Dremel too. I left newels long, to be cut later to the height set by the assembled handrail. Newels are lagged in place through 1-in. holes that were later plugged.

With newels bolted temporarily in place, I chose the balusters and established their spacings, holding them in place temporarily with nylon line. When they looked right, I numbered the pieces, took them down and made the rails.

The curving starter rail was tricky to cut and fit, but a sandbag on the table of the miter saw helped to keep oddly shaped pieces situated correctly and safely. The handrail is sanded to 220 grit and finished with tung oil.