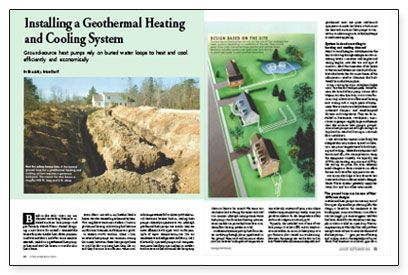

Installing a Geothermal Heating and Cooling System

Ground-source heat pumps rely on buried water loops to heat and cool efficiently and economically.

Synopsis: Geothermal heating and cooling systems rely on some fancy mechanical engineering and the inherent stability of subterranean temperatures to operate. This article discusses three major types of systems and looks in detail at an installation of a horizontal ground-loop system in North Carolina. A sidebar explains how a geothermal heat pump works.

Back in the early 1980s, my mechanical-contracting business installed air-to-air heat pumps and gas furnaces. Period. Then I started designing a new house for myself. I oriented the house for passive-solar heat, chose premium windows and doors, and after some intensive research, settled on a geothermal heat pump to heat and cool the house. It was the clear first choice.

Soon after I moved in, my brother built a house. He also wanted a geothermal system. Two neighbors were next. Before I knew it, geothermal heating and cooling had become my full-time business, and business is good.

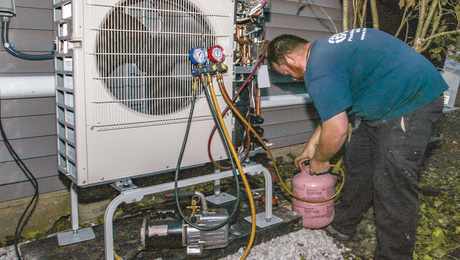

In eastern North Carolina, where I live, air-source heat pumps are common. During the winter, however, these heat pumps have to work harder to extract heat from the air, and they become less efficient. When outside temperatures fall to about 30°F, electrical-resistance heaters kick in, making heat pumps relatively expensive to run. Although geothermal heat pumps are similar, they are more efficient. Both types work on the principle of vapor compression—just like air conditioners and refrigerators. Electrically operated pumps and compressors move heat from one medium to another. But because no fuel is burned, the heat-pump geothermal units are quiet. Mechanical equipment is inside the house, which is not the case with air-to-air heat pumps or central air-conditioning units, so the landscape is much more appealing.

System is sized according to heating and cooling demand

Heat-loss and heat-gain calculations are the key to choosing the right equipment. For an existing house, I measure wall lengths and ceiling heights, note the size and type of windows, check the orientation of the house to the sun, and determine what kind of insulation the house has. For a new house, all the information I need to determine the loads should be on the house plans.

Using a room-by-room calculation helps me to size the ductwork properly. WaterFurnace, the brand of heat pump we use, allows us to offer zoned heating and cooling with a single piece of equipment. These units use multiple thermostats, motorized dampers, and variable-speed blowers and compressors. They can be installed in basements, crawlspaces, attics, closets, or garages. Slightly larger and heavier than the air-to-air heat pumps, ground-source heat pumps are still light enough to be placed on standard framing in a second-floor installation.

I also ask whether anyone in the family has allergies that may require special air filtration. Set-point temperatures for both heating and cooling—where the equipment will turn on and off—also are important in sizing the equipment correctly. We typically use 70°F for the heating set point and 75°F for the cooling set point, but even relatively small changes in these numbers can affect the size and cost of the equipment we use.

Our system also helps to heat domestic hot water with a built-in device called a desuper-heater. These systems generally supply between 50% and 70% of hot-water needs.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Plate Level

Original Speed Square

100-ft. Tape Measure