What Are Structural Insulated Panels?

SIPs provide solid structure and insulation for walls and ceilings

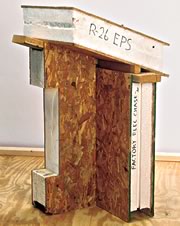

Structural Insulated Panels (SIPs), a “new” building material that has actually been in use since the 1940s, consist of two outer skins and an inner core of an insulating material to form a monolithic unit. Most structural panels use either plywood or oriented strand board (OSB) for their facings. OSB is the principal facing material because it is available in large sizes (up to 12-ft. by 36-ft. sheets), and manufacturers have used OSB facings on structural panels used for the rigorous testing needed for code approvals. Structural panels can also have other materials, such as drywall, sheet metal, or finish lumber, laminated onto the OSB structural facings at the factory. This service eliminates one more step in the building process and speeds up assembly time.

The cores of SIPs can be made from a number of materials, including molded expanded polystyrene (EPS), extruded polystyrene (XPS), and urethane foam. Some SIP producers use isocyanurate foam as the core material, but since there is only a slight chemical difference between urethane and isocyanurate, I will refer to both of these core materials as urethane foam. Urethane foam panels comprise only about 5% of the panels produced.

The insulating core and the two skins of a SIP are nonstructural and insubstantial components in themselves, but when pressure-laminated together under strictly controlled conditions, these materials act synergistically to form a composite that is much stronger than the sum of its parts. Panel manufacturers supply splines, connectors, adhesives, and fasteners to erect their systems. When engineered and assembled properly, a structure built with these panels needs no frame or skeleton to support it.

Structurally, a SIP can be compared to an I-beam: The foam core acts as the web, while the facings are analogous to the I-beam’s flanges. All of the elements of a SIP are stressed; the skins are in tension and compression, while the core resists shear and buckling. Under load, the facings of a SIP act as slender columns, and the core stabilizes the facings and resists forces trying to deflect the columns. The thicker the core, the better the panel resists buckling, so larger-core SIPs offer more insulation and are stronger as well.

Stock SIPs are produced in thicknesses from 4-1/2 in. to 12-1/4 in. and in sizes from 4 ft. by 8 ft. up to 9 ft. by 28 ft. Their R-values range from about R-15 for a 4-1/2-in. EPS or XPS panel to higher than R-32 for a 6-1/2-in. urethane panel. A 12-1/4-in. EPS panel is rated at R-45. Custom sizes and configurations are also available from some manufacturers, and virtually any bondable material can be applied as the facing material. The flexibility of the manufacturing process means that custom lengths and skins can be ordered for nearly any application.

Currently, SIPs are used primarily in residential and light commercial applications. While neither EPS nor urethane foams (the main core materials) are particularly flammable, they will burn when exposed to flame, so their use in high-rise or large public buildings without extensive fire suppression technology is limited. SIPs perform well under various flame and fire testing Most buildings higher than three stories are subject to a different set of building regulations due to the loads applied to the walls and floor systems. The current standard for this type of building is to construct the frame using structural steel members, then to infill the walls, floors, and partitions (see The regulatory environment). There is great potential for SIPs and curtain-wall panels to be used in these applications.

The regulatory environment

The manufacture and production of a material or an assembly of materials for sale in this country to use in structures that people live and work in is a highly regulated undertaking. In some areas, local building code enforcement authorities have been reluctant to accept SIPs because they are not familiar with the connection details and product testing results. But this situation is changing. The dominant code bodies — the Council of American Building Officials (CABO), the International Conference of Building Officials (ICBO), Building Officials and Code Administrators International (BOCA), and the Southern Building Code Congress International (SBCCI) — are being replaced by the International Residential Code (IRC), which went into effect in early 2000. The new IRC contains a section specifically establishing energy-related requirements for new construction.

There are also a number of signs that the U.S. government is taking steps to encourage greater awareness of energy issues and reward people who take this approach. Efforts by the Office of Science and Technology have led to the development of the Partnership for Advancing Technology in Housing (PATH). The PATH initiative seeks to reduce the environmental impact and energy use of new housing by 50% or more by 2010. SIPs are a featured technology in PATH’s vision.

Not All Building Panels Are SIPs

Building panels come in many configurations, known variously as foam-core panels, stress-skin panels, nail-base panels, sandwich panels, and curtain-wall panels, among others. Many of these building panels are nonstructural, while some have no insulation. And the term “panelized construction” can also include prefabricated stud walls and other configurations associated with the modular industry.

Michael Morley is a builder in Lawrence, Kansas, who specializes in structural insulated panel construction. Photo by: Michael Morley; drawing by: Ron Carboni

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Disposable Suit

Caulking Gun

Loctite Foamboard Adhesive