Concrete Mix Design

This excerpt from Fu-Tung Cheng's breakthrough book, Concrete Countertops, describes some of the limitless color possibilities

Making concrete is a bit like baking a cake; you don’t need a lot of fancy equipment, tools, or materials to achieve pleasing results. To bake a cake, you might choose to buy a box of mix at the grocer, add water, stir, then pour the batter into a mold and insert it into a preheated oven. And you’d get credible results. But creative souls, not content to simply stir and bake, will begin to experiment — adding nuts and raisins perhaps, or maybe extra chocolate chips. Then, emboldened by the results, they may decide to dispense with the mixes entirely and turn to fresh ingredients and sophisticated recipes, discovering new dessert delights. The variations and creative possibilities become endless; the leap from Betty Crocker to sophisticated French pâtisserie is a leap of faith and imagination.

Leftover concrete, of course, can’t be consumed the next day, so we must be careful not to stretch the analogy too far. But with concrete, as with cake, you can simply toss together your ingredients — some gravel, sand, and cement, or bagged readymix available at your local hardware store — add water until the mix looks about right, hoe for a while in a wheelbarrow, and then dump it all into a mold. Chances are fairly good that you’ll end up with a workable, fine-looking piece.

At Cheng Design, we have worked up some recipes of our own that make the leap to “French pâtisserie,” and a basic recipe from our repertoire is included in this chapter. It’s one we’ve devised through trial and (a bit of) error, and find to be a useful architectural concrete mix that gives consistently good results. We first designed the mix for countertops, but it’s equally appropriate for floors, room dividers, and any other application in which the look of the concrete’s finished surface is paramount.

We describe this mix in this chapter and provide a precise formula for it. We offer it for those of you who like plenty of creative and technical control over the results of your endeavors, and we suggest you think of this mix as a starting point. You might try different mixes, using a variety of ingredients in varying proportions. You may find a mix that suits your needs or aesthetics much better than the mix outlined here. Also, bagged concrete and readymix — concrete that is delivered to the site in a transit mixer–are options, and both have advantages and disadvantages, which we’ll discuss later in this chapter…

Pigments

The most common and least expensive pigments are the blacks, the browns, and the reds–from carbon and mineral black and iron oxides. Blues and greens — from cobalt, ultramarine, and phthalocyanine blue; chromium oxide; and phthalocyanine green — are a bit more difficult to find, and they can be much more expensive, depending on their source. We generally combine pigments ourselves to achieve the desired color, but you might want to try one of the many off-the-shelf, premixed colors from a variety of suppliers; these give reasonably predictable results.

When deciding on a color, be aware that lots of things can affect the finished look. For example, while all Type II and Type III cements are gray, different brands vary in shading, which can affect the color of the finished piece. Likewise, sand varies widely in color from locale to locale, and these variations can also affect the color. How you cure the piece, how (or whether) you grind it, and what you use to seal the concrete can also affect the color.

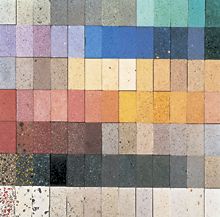

If an exact color is important, it’s a good idea to make several samples using a variety of color mixes and materials available in your area (see Four sample mixes). Experiment to see how various ingredients, grinding, and sealing influence the finished look. Be aware that most concrete colors fade in sunlight, some more than others. Yellows and reds made with iron oxides are fairly stable in the sun. Blues and carbon black are more likely to fade to concrete’s natural gray over time.

Some pigments — chromium oxide and cobalt blue, for example — contain heavy metals, so they should be handled carefully. Wear a respirator-type mask, gloves, and protective goggles. When washing out the mixer after using such pigments, pour the wash water into a catch basin (we make a frame of 2x4s or 2x6s lined with plastic sheeting for the purpose) and let the water evaporate. Dispose of the solids at an appropriate facility for hazardous waste.

Pigments are measured as a percentage of the total weight of the cement being used. Because pigments tend to weaken concrete, as a rule of thumb, their total weight should not be more than 10 percent of the weight of the cement (the blue and black pigments used in the piece featured here totaled 8.7 percent of the cement weight). We have, on occasion, pushed pigmentation to as much as 15 percent without problems, but at this level, there is a danger that the durability of the concrete’s surface will be compromised. Generally, we try not to go overboard with pigments; intense colors look artificial, and we prefer the natural, earthy feel of more lightly colored concrete.

Four Sample Mixes

Pigments and readymix

When ordering readymix, you may need to specify the amount of pigment by weight for the entire load, not just for the amount of concrete you plan to use. Since most readymix suppliers won’t deliver less than a half a yard (and some may not deliver less than a full yard), this can be expensive if you’re using lots of the higher-end blue or green pigments. If cost is a consideration, you might want to add the pigments to the readymix after it’s delivered, assuming you have enough clean containers to hold it.

Also, not all readymix plants have a wide range of pigments (some may not have any pigments other than black). Thus you may need to get pigments from a local supplier or order them, then deliver the colors to the readymix plant to be included in your load. And be aware that some suppliers will tack on a surcharge for cleanup after delivering pigmented concrete.

Designer Fu-Tung Cheng heads the Berkeley California firms of Cheng Design and Cheng Design Products. His hands-on approach to residential architecture and kitchen and product design has won him several awards and recognition for innovation and creativity. Cheng’s contemporary-crafted houses have appeared in numerous architecture and design publications. Photos by: Matt Millman