When Congress mandated, in 1994, that toilets use only 1.6 gallons per flush (gpf), the plumbing industry panicked. Back then, America’s porcelain behemoths guzzled more than three gallons per flush—and didn’t always work very well at that. Meeting the new low-flow law seemed impossible. How could manufacturers pack enough flush power into such a small amount of water? And could anything remotely stylish be adapted to the new law?

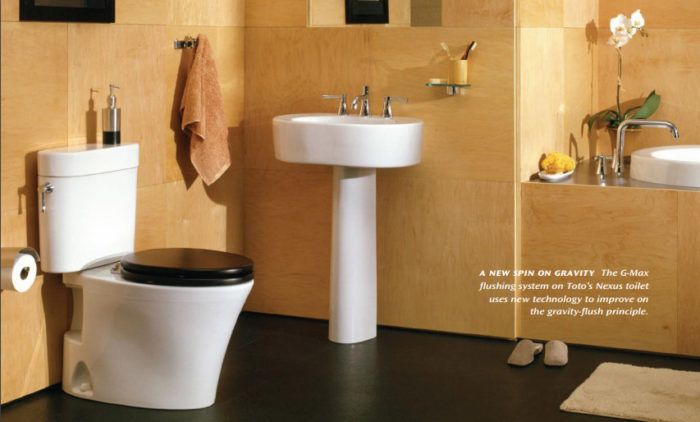

A decade later, toilets have been through a quiet revolution and have come out working and looking better than ever. Toilet styles today are all over the map, from traditional to Victorian to contemporary, and most don’t cost a fortune. (Toilets range in price from $100 to $800, with most styles in the $200 to $400 bracket.)

But the biggest change has been “under the hood,” where manufacturers rose to the challenge and figured out how to make the 1.6 gpf mandate work. One big improvement, now standard, involved glazing the trapway, which is where waste goes after you flush. The smoother surface helps everything move more quickly. Another change was a larger flush valve, which is the hole at the bottom of the tank where fresh water enters the bowl. To increase water flow even more, manufacturers used computer programs to design trapway and bowl shapes with less resistance.

The innovations didn’t happen overnight. Early models rightly earned the nickname “two-flushers” for their inability to get the job done the first time. But recent independent studies confirm what plumbers and homeowners have already noticed: Today’s models work very well, even if clogs still occasionally happen.

An effective flush

The first decision when buying a new toilet is choosing the type of flush mechanism—gravity, vacuum-assisted, or pressure-assisted.

Most toilets operate on the same gravity principle that’s been in use since the 19th century. Pushing the lever opens a flush valve that sends stored water from the tank rushing into the rim holes (to clean the bowl sides) and through a larger hole at the bottom of the bowl called the siphon jet. Water moving through the siphon jet pushes the bowl water up over a built-in trap behind the bowl, starting a siphon effect that draws the old water into the trap and down through the drain. Once the bowl empties, air enters the trap and breaks the siphon, allowing the bowl and tank to refill for the next flush. In essence, the weight of the water itself is what powers the flush.

For more photos and details on toilets for your bathroom, click the View PDF button below.