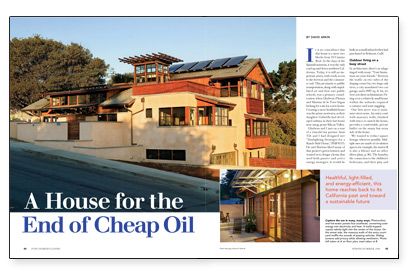

A House for the End of Cheap Oil

Healthful, light-filled, and energy-efficient, this home reaches back to its California past and toward a sustainable future.

Synopsis: In Belmont, California, architect David Arkin has designed a house that heats and cools itself, and generates it own electricity. A passive/active system banks the sun’s heat in 2-ft.-deep sand beds underneath the floor slabs. The heat slowly rises into the home and is typically enough to last for up to three weeks of overcast skies. On the roof, the photovoltaic array feeds electricity into the grid until called on for use in the house. Besides reducing energy consumption, the house lessens its impact on the environment through the use of renewable and recyclable building materials such as FSC-certified wood; bamboo; salvaged sheathing, doors and windows; and rubber roofing tiles.

It is no coincidence that this house is a mere two blocks from El Camino Real. In the days of the Spanish missions, it was the only road up and down northern California. Today, it is still an important artery, with ready access to the freeway and the commuter rail. This proximity to public transportation, along with unpolluted air and first-rate public schools, was a primary consideration when Gladwyn d’Souza and Martina de la Torre began looking for a site for a new house. Creating a more healthful home was the prime motivator, as their daughter Gabriella had developed asthma in their last house near smog-prone Silicon Valley.

Gladwyn and I met on a tour of a remodel my partner Anni Tilt and I had designed. He and Martina liked many of that project’s green features and wanted us to design a house that used both passive and active energy strategies. It would be built on a small urban lot they had purchased in Belmont, Calif.

Outdoor living on a busy street

In architecture, there’s an adage tinged with irony: “Your limitations are your friends.” Between the traffic on two sides of the sloping corner lot, two large oak trees, a city-mandated two-car garage, and a 4987-sq.-ft. lot, we were not short on limitations. Fitting even a relatively small home within the setbacks required a variance and some juggling.

Our first move was to minimize street noise. An entry court with masonry walls, finished with stucco to match the house, provides a comfortable, private buffer on the sunny but noisy side of the house.

We wanted to reduce square footage wherever possible. Multiple uses are made of circulation spaces; for example, the stairwell is also a library and an office. The laundry, the connection to the children’s bedrooms, and their play and homework areas are all one space, and the short hall to the master bedroom is also a dressing/makeup area. The kitchen, dining, and living areas are a single volume. A high ceiling and southeast-facing clerestory windows give this room a sense of spaciousness. Long views through the house, the entry court, and the oak trees also help the room to live large.

The guest bedroom has easy and unobstructed access for aging grandparents, allowing both entry and contiguous living on the main level of the house. The bathroom in this suite, built with universal-design principles in mind, doubles as a powder room.

This house heats and cools itself, and generates its own electricity

Unlike cars, buildings are fixed in the landscape and can be tuned to optimal performance based on their latitude, microclimate, and other circumstances. Where feasible, we like to point houses toward the morning sun, especially in moderate climates prone to late-afternoon overheating.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Roof Jacks

Flashing Boot Repair

100-ft. Tape Measure