Houses Need to Breathe … Right?

Tight houses are energy efficient, but good ventilation is essential to make them healthful and comfortable.

Synopsis: Sick-building syndrome. Toxic mold. Asthma. The EPA lists poor indoor-air quality (IAQ) as the fourth-largest environmental threat to our country. The American Lung Association notes a link between IAQ and asthma, the most serious chronic illness of American children. Are tight houses poisoning us? Tight houses save energy, but they also can trap pollutants that are generated indoors. The energy savings from a tight house more than offset the cost of operating a small fan for mechanical ventilation; a better option than relying on random leaks to ventilate a house.

I hear it all the time: “Houses are too tight.” “Houses didn’t used to make people sick.” These assertions seem well founded: The most serious chronic illness of American children is asthma, and the Environmental Protection Agency lists poor indoor air quality among its top five environmental threats. Are tight houses poisoning us?

There’s no disputing the cause-and-effect relationship between tight houses and indoor-air pollution. In theory, the solution is simple: If you build tight, you must ventilate right. In practice, though, ventilating right is complicated and controversial. In 2003, I chaired an American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) committee that passed the country’s first residential ventilation standard, which gives builders and designers guidelines for providing good indoor air while keeping utility costs low.

Ventilation is manifold in house systems

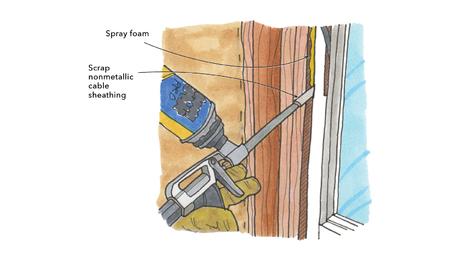

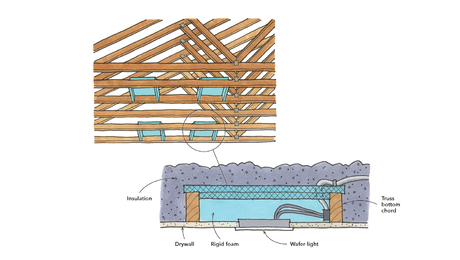

Before I go farther, let me define ventilation. The word ventilate comes from the Latin ventuilare, and it means to expose to the wind. Although this may sound like some creep in a raincoat, the real story is more complex. Ventilation is used many ways when describing how a house works: There’s crawlspace ventilation (often bad), ventilated siding assemblies (good), and roof ventilation (sometimes bad, some times good). We’re not talking about that stuff. Here, we’re talking about mechanical ventilation, using fans to blow out old air (exhaust), suck in new air (supply), or both (balanced ventilation).

Leaky houses are not the answer

On average, the air in older homes is replaced once every hour (1 ACH, or air change per hour) because older homes have a built-in ventilating method that’s simple and reliable: leaks (or infiltration). The average house in the United States has about 3 sq. ft. of holes in it, but infiltration is a pretty bad way to ventilate because it wastes a tremendous amount of energy. you could plaster that 3 ft. of holes with $20 bills, and the work would pay for itself in less than a season.

Since the oil shock of the 1970s, houses are tighter and better insulated. Even conventionally framed new houses can be 5 times tighter than the general stock. Many builders and designers are tempted to take the Goldilocks approach and to look for that level of leakage that is just right, neither too little nor too much. Unfortunately, there is no hole for all seasons. The best a leaky house can do is waste energy much of the year and be under-ventilated the rest of the year.

Won’t open windows provide the ventilation we need? In principle, yes, but in practice, no. People are pretty bad at sensing exactly how much, how often, and for how long to open the window to provide optimal ventilation. Furthermore, noise, dirt, drafts, and creeps in raincoats dissuade people from opening their windows.

For more photos and details on indoor ventilation, click the View PDF button below.