In the Golden Gate’s shadow

By creating more than just an entryway, craftsman Julian Hodges transcends the idea of conventional gate construction

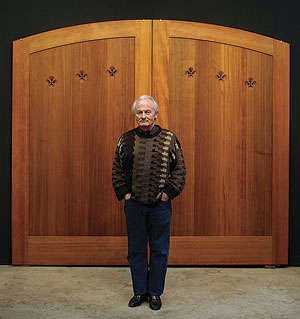

Artfully designed and constructed gates are fascinating. They can set a mood for a house or garden. Gates can beckon, or they can shout “stay out!” They also can reveal something about their builder. For 25 years, gates have engaged the creative impulse of Julian Hodges, an English artist transplanted to Berkeley, Calif. Starting with clear, vertical-grain redwood and working alone, he designs every element of his gates down to the lights and latches. Hodges’s astonishing oeuvre spans from Gothic to modern, from Craftsman to Japanese, and each gate exhibits exquisite joinery and an artist’s eye.

Gothic ancestry

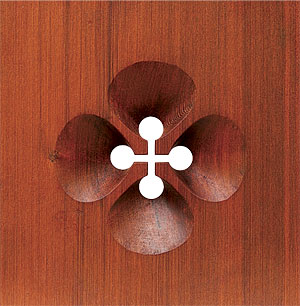

Julian Hodges is fascinated with the flower or four-leaf-clover shape of the quatrefoil, one of his signature elements. Quatrefoils originated as architectural tracery—ornamental stone openwork—in Gothic windows. Hodges sees limitless possibilities in the sculptural interplay of orbs and cusps carved in wood, and has produced whimsical versions. These demanding flourishes must create a mirror image on both sides of the board.

Daniel Moore

Daniel Moore  Daniel Moore

Daniel Moore

Sharp angles, gentle curves

When Hodges first saw the dramatic gables of this thoroughly modern house, he knew the “assertive architecture” demanded a similarly commanding gate. The 6-ft.-tall, 1-ft.-sq. concrete columns lend scale and formality, and the rounded gate top serves as a counterpoint to the emphatic roof angle above.

As he does with all his gates, Hodges designed and built the composition, working with western red cedar, concrete, steel, and copper. A mailbox (visible only to Hodges, the homeowner, and the letter carrier) is hidden in the potato vines. Copper details such as these Art Deco-style windows and fan-shaped lights are recurring design elements in Hodges’s gates and are left to weather naturally.

Hodges’s romantic notions about gates guide his lighting strategy. A low-voltage incandescent light gently washes the concrete and sets the mica and copper fixtures aglow—an outcome more theatrical than illuminating.

Copper-top back gate

Identical Craftsman-inspired gates guard the front and rear of the house. The fence is a pleasing repetition of the gate’s slats but is understated intentionally so that the gate is unquestionably the focal point. The homeowners asked for a chevron theme in the arch, which repeats throughout the gate. On the lower edge of the top rail, the inverted step shape mirroring the copper detail is reminiscent of a common regional flourish called a cloud lift.

The top of the gate is wrapped on all four sides with 1/8-in.-thick hammered copper. In a highly labor-intensive process, Hodges “explored the foothills of carpal-tunnel syndrome,” creating the textured caps with overlapping blows of a planishing hammer.

Steel steps in

Hodges began experimenting with steel frames on large gates as a way to control costs. By joining two shallow arcs at sharp angles, he created an ellipselike shape evoking a traditional scooptop gate. The asymmetrical sections create a pleasing tension in the design.

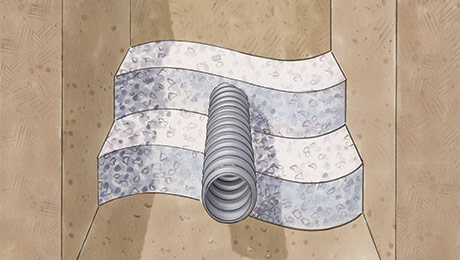

To hang heavy gates from concrete posts, Hodges devised an innovative, adjustable threaded hinge. A few deft turns of a nut on each hinge adjusts the gap between the gate sections— just the right thing when summer temperatures cause the metal frame to expand.

Asian influence

Old-growth redwood has become a scarce commodity. The 6-ft.-long arched beam, cut from a 6×12, most likely would be taken from a lamination today. When Hodges comes across a rare large timber or a cache of particularly appealing boards, he believes it’s worth the expense to add them to his inventory awaiting projects he deems “especially interesting.”

Guardian gates

At 14 ft. across, 3-1/2 in. thick, and 500 lb. apiece, these redwood gates studded with copper-clad rivets fairly cry out for passersby to keep on moving. The copper lamps initially were rejected by the client as too “Craftsman-ly and Japanese.” When architect Joseph Esherick (who designed the house hidden behind the gate) saw the plans, the lamps were back in the picture.

Dog’s best friend

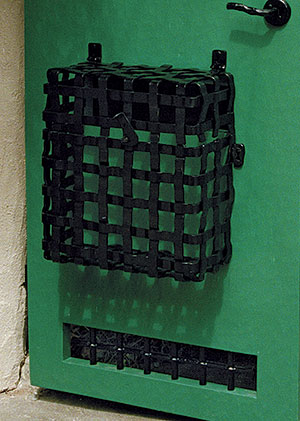

The homeowner wanted a window in his gate so that he could look out onto the street, a pastime also enjoyed by his dog. The long, narrow window at the bottom lets the dog lie with his paws under the gate and watch the letter carrier’s approaching feet. The woven steel basket on the back protects the pup from weighty manuscripts sent to his master, an editor.

This whimsical gate begs to be touched—whether it’s the forged ironwork of the mortise-and-tenon grille, the florid strap hinges, or the adzed redwood.

Julian Hodges

Julian Hodges  Julian Hodges

Julian Hodges

Timelss design, timeless construction

When Hodges, an art-school-trained potter, moved to Berkeley in 1971, he found little appreciation for sophisticated ceramics in a town where every other person styled himself or herself as a potter. He was working for traditional Japanese teahouse builder Makoto Imai when he came to the conclusion that building gates would allow him a range of opportunities for creative expression and for complete control of the design and construction processes. The Japanese aesthetic is evident in many of Hodges’s gates, and so is the traditional philosophy that prizes becoming absorbed in the process and taking satisfaction in incremental steps toward perfection. Hodges is known for his fastidious (as he prefers to define it) attention to detail, and he guarantees his gates will never sag; in fact, as the lichen and the patina take hold, they seem to improve with age.

If you’re wondering how much this approach costs, it depends on the level of detail. A small garden gate might start at $5,000, and a large driveway gate could be $30,000 (with installation extra in each case).

See more gates at www.julianhodges.com or click to watch a video of Julian Hodges at work.

Photos by: Gene DeSmidt, except where noted