Our myopic building codes

Are building officials' practices encouraging builders to perform mediocre work?

Imagine two builders in your community. One knows the building code as a set of minimum standards and builds only to those minimums, producing the worst building he legally can. The other always is pushing the envelope at the opposite end of the spectrum, trying to build the most energy- and resource-efficient, least toxic, most environmentally and socially responsible building possible. Which builder, do you think, holds the record for the fastest and easiest time getting a set of plans through the building department, and which holds the record for the longest and most brutal experience? Nobody intends to give a pass to the worst builder and to beat the crap out of the best one, but that’s what our system does.

What if building officials reviewed the plans of the best builders first instead of putting them on the bottom of the pile because of all the complications? What if officials met with builders to learn why they are doing what they’re doing, what the benefits are, and to whom those benefits accrue? What if we all saw our building departments as a community resource for the best houses, not just as the building police preventing the worst?

Seeing the larger context

According to the International Code Council (ICC), the purpose of the International Building Code is to “safeguard public health, safety and general welfare… from hazards attributed to the built environment.” The code then prescribes how to accomplish that purpose, detailing means of egress, fire safety, structural integrity, and so forth. In fact, our modern codes are extremely good at enabling us to design and build structures that rarely fall down, burn down, trap people in emergencies, electrocute people, expose them to raw sewage, let them fall from high places, or suffocate them.

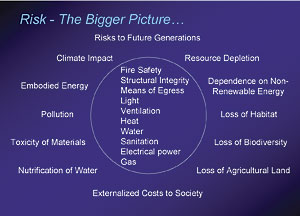

Through the microscope of the building code, our responsibility for safeguarding public health, safety, and welfare appears to have been carried out. But when you take your eye away from that microscope, you see a set of risks many orders of magnitude greater—risks for billions of people, not just the occupants of specific buildings.

We have long assumed that the hazards caused by the built environment are limited to those that occur at a building site and during the life of a building. In reality, hazards begin with the acquisition of resources and extend through their processing, transport, and installation. The hazards include any waste and pollution generated during construction. They also include the environmental impacts of a building’s operation, maintenance, repair, and remodeling, and they extend into the future, far beyond the life of a building.

Whether we are talking about how buildings contribute to global warming; their dependence on fossil fuels and petrochemicals; the range of environmental impacts from pollution to deforestation to the use of nonrenewable resources to loss of habitat and productive farmland; or the range of impacts on water, air, and human health, many hazards attributable to the built environment are outside the scope of our current building code. And we are constructing millions of buildings every year without understanding this oversight.

What’s risky now?

When you look at how buildings are designed and constructed, you realize that many of our common practices, which previously have appeared extremely safe, begin to look rather risky. Likewise, many of the practices that look risky now begin to look far safer in this larger frame of reference.

If you design a home to heat, cool, and ventilate itself passively, without external power or mechanical systems, you are required by code to provide absolute proof that it will work—not just that it will be safe, but that it will perform to quite narrow and unnatural comfort parameters. You also are required to add backup mechanical systems to ensure that you can maintain those comfort levels. Yet the code has no problem with homes that flaunt passive-solar design principles, that have inoperable windows and rooms without natural light or ventilation, and that require massive mechanical life-support systems to maintain minimum utility, making houses dangerous or possibly lethal when they lose their external power supplies. Oddly, the building code requires no natural backup systems to make these homes safe when, inevitably, they lose power—no provisions for emergency lighting, heating, cooling, and ventilating.

The benefits of passive-design strategies extend beyond energy savings. People can subsist in a well-insulated building designed at least partially to heat and cool itself and to provide fresh air to each room until power is restored.

The building code also readily allows the use of industrialized materials and systems that travel thousands of miles to a building site and have huge ecological footprints. At the same time, tremendous scrutiny is focused on natural materials such as rammed earth, straw bales, or timber from your own land that hasn’t gone through an industrial process. When you consider the negative impact of the acquisition of raw materials; the waste, pollution, and energy intensity of manufacturing processes; and the risks associated with the ultimate disposal of the materials that go into our buildings, many lower-tech, more-local materials and systems seem to be less-risky alternative

Awareness is the key

Our building code is a gate, and code officials are the gatekeepers for the crucial and enormous changes that must happen in the next decade if we are to avoid the catastrophic consequences of global warming, peak oil prices, and the impact of 6.5 billion of us on this planet. Fortunately, some building departments around the country already are beginning to view the code in a larger, more sustainable context.

Seattle, for instance, is committed to becoming a sustainable city. City leaders began by combining the planning and zoning department with the building department, creating the department of planning and development. This reorganization clarified the relationship between the regulatory realm and the city’s sustainability goals and comprehensive plan. The department also hired a green-building expert to oversee the proper handling of green projects and to teach the staff about green building.

When the Seattle City Council passed an ordinance requiring municipal building projects to meet the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) silver standard, the city trained a couple of dozen staff people in various departments to be certified as LEED-accredited professionals. The energy and morale of Seattle officials are high because they see themselves as partnered with and supporting the best designers, builders, developers, and projects. The building department has created great information resources for professionals and the public, and the staff’s commitment goes far beyond just talking about how to do it.

“If you want to see these kinds of changes where you live, get involved locally.”

The ICC is internalizing these changes as well. The council recently moved its headquarters into a green building on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C.—a LEED silver building. The board of directors has passed a sustainability and green-building policy statement, and is moving to develop a guide to sustainability and green building for code officials through a partnership with the U.S. Green Building Council.

If you want to see these kinds of changes where you live, get involved locally. If you don’t think your building department has well-trained or well-qualified people, then advocate for adequate training resources related to sustainable building and development practices, and for hiring more-qualified people. Think about what the ideal building department would be like, and begin creatively and constructively introducing those ideas through your everyday encounters and communications with elected officials and others in your local government. If you aren’t getting the government you think you deserve, but you aren’t engaged in changing it, then you have no basis for complaining.

Yes, specific portions of the building code need to change, and that will take time. But once we all are aware of the full range of risks that our buildings create, and where and for whom those risks occur, the transition toward sustainable buildings and communities won’t be derailed by building codes or by the people who enforce them. The same codes can be enforced either to protect the narrowest interpretation of risk or the broadest. Awareness of what we all have at stake is the key.

Watch an excerpt from the author’s DVD, Building Codes for a Small Planet, which includes a visit to an off-the-grid straw-bale house in Santa Margarita, Calif.