Designing accessible entries

With the right guidelines, everyone can easily construct and benefit from an accessible entry to their homes

When a client asks me to add a ramp to an existing home, my first questions are “Who will use the ramp?” and “What are their needs?” The ramp might be for the client, for a family member, or for a friend. If that’s the case, the ramp can be tailored for a specific ability.

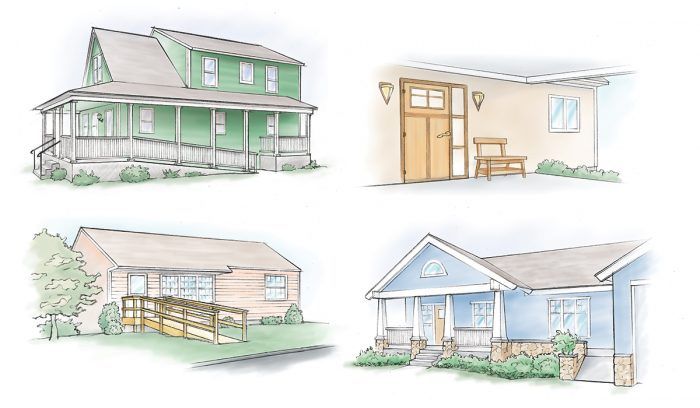

Increasingly often, however, I find that homeowners are planning for people with a wide range of ages or abilities to visit their home. Their motivation is the forward-thinking realization that life includes changes and that the abilities we have now are not permanent. Everyone from the stroller set to seniors will benefit, temporarily or long term, by having a no-step entrance to a home. A no-step entry fits the principles of universal design. This philosophy calls for inclusive design usable by as many people as possible, regardless of age, ability, or circumstance. In keeping with this concept, I like to provide the choice of stairs or a ramp at an entry so that people can choose the one they are most comfortable with. For example, some folks who use leg braces or crutches find shallow steps easier than a ramp.

My first task in determining where to add a ramp is to review the family’s primary entrance. Most clients with a disability prefer to enter their home using the same entrance as the family members who climb stairs, whether that’s through the garage, a side door, or the front door.

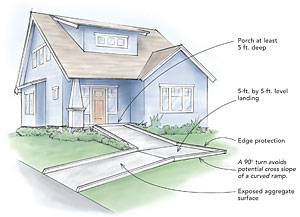

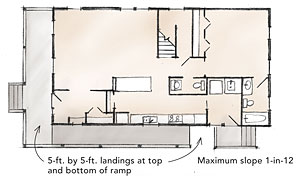

The elevation change at this primary entrance determines the ramp’s construction. A ramp cannot be steeper than 1-in-12. However, the shallower and shorter a ramp is, the easier it is to use, so I always try to minimize slope. A slope of 1-in-20 is easy to climb but requires a great deal of space. If the level change at the entrance is 18 in. or less, I prefer to overcome that difference in the landscaping. A landscape ramp is unobtrusive and easy to navigate.

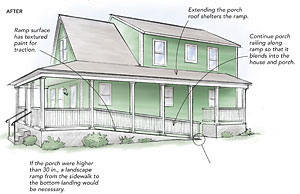

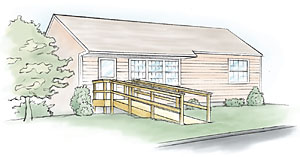

A rise between 18 in. and 30 in. is usually accommodated with a structural ramp. Too often, a ramp is a utilitarian construction tacked onto a house. When a ramp is integrated into a home’s style and architecture, those used to looking for them will see it, but the ramp won’t be obvious amid the surrounding landscape and structure.

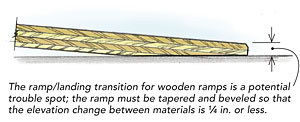

Be sure the dimensions meet safety standards for ramps (see Ramp basics, below). The choice of the ramp surface is critical. Decking planks and other materials that have gaps or height variations in the surface are jarring and can catch the front wheels of walkers and wheelchairs.

Ramping an entry more than 30 in. above grade requires an extraordinary amount of space. If you have the room, it might be possible to wrap a ramp around several sides of the house, but a mechanical lift could be a less-intrusive, cheaper option.

A landscape ramp is the best option

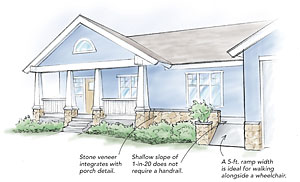

If the height between the entrance and the street or driveway is 18 in. or less or if you have plenty of space to incorporate the necessary slope, a landscape ramp blends seamlessly with the house, works well for people with varying degrees of mobility, and doesn’t advertise itself.

The ramp surface should be textured to provide traction. All ramps should have side protection to prevent a wheelchair or walker from rolling off the edge. In this case, it could be as simple as shrubs along the border or an integral curb.

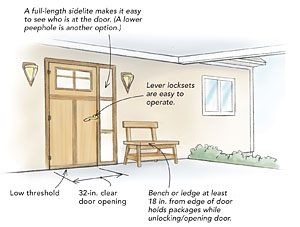

Don’t forget the door

An accessible entry includes the doorway. A 36-in.-wide door provides 32 in. of open clearance, adequate accommodation for a wheelchair. This is one case where bigger isn’t better. Although a wider door provides more clearance, the added width and greater weight make it more difficult to open. You need at least a 5-ft. by 5-ft. space on both sides of the door for maneuvering. Use the lowest threshold you can get away with and still keep out the weather. While completely flat is the ideal, 1/4 in. is manageable.

A ramp should blend in with the style of the house

Before

Before

Too often, ramps added to an existing house are ungainly structures projecting awkwardly from the front door. Integrating a ramp into the porch creates an inviting, accessible entry that blends in. The side location is accessible from both the front sidewalk and the garage behind the house.

This steep ramp requires handrails on both sides, but it’s short enough that an intermediate landing isn’t necessary. Marine plywood with textured paint is an excellent ramp surface in this situation.

Ramp basics

• Slope: Maximum slope is 1-in-12; shallower slopes between 1-in-15 to 1-in-20 are recommended.

• Landings: Minimum 5-ft. by 5-ft. level space is required at the top and bottom of a ramp, at switchbacks and turns, and to break up long runs. Power wheelchairs or scooters could require more maneuvering room.

• Length: 30 ft. is the maximum run between level landings; 20 ft. is a more comfortable distance.

• Width: 3 ft. is the minimum clear width between handrails or edge protection; 5 ft. is ideal for someone to walk alongside a wheelchair.

• Handrails: Ramps steeper than 1-in-20 require a 34-in.- to 36-in.-high handrail on both sides.

Stairs and ramp provide options

Here, the front porch is served by both a short flight of steps and a ramp from a car turnaround. The shallow, wide ramp allows someone to walk alongside a person in a wheelchair or using a walker. The stone-veneer planters and the low wall continue the materials that are used in the pillars on the porch.

The low wall provides edge protection for errantly directed wheels. By following the slight slope of the ramp, the wall is a small visual cue that a ramp lies behind it.

Getting the slope right isn’t good enough

This ramp would let a wheelchair user flee the house in the event of a fire, but it’s not good for much else. No thought has been given to accessing the ramp. With a curb barring the way from the street and an expanse of grass between the ramp and the street, a wheelchair user can’t get to the door without assistance.

Poorly designed ramps like this are all too common. The straight-run design and unadorned materials give it the air of a temporary bandage to be discarded or neglected in short order. A combination of landscaping and a small entry porch would provide safe, self-sufficient access and enhance the facade.

Drawings by Chuck Lockhart