Synopsis: To have a long life, a fence built in a climate like that of Portland, Oregon, needs to have special attention paid to details. This fence built by Scott Grice and Mark Newman is built to last, and features beautiful furniture-grade details. To help ensure that the fence lasts, Grice built the frame of steel and set it in concrete. Then Newman added the wood details; his weather-savvy building strategy is featured in a sidebar to this article.

When my colleague Mark Newman and I initially reviewed the plans for this fence, one detail the architect specified jumped out at us. The plans called for a long run of tall 6×6 cedar posts milled to fit over 2-in. steel tubes anchored in concrete. This seemed like a lot of work with little chance of precision and a lot of potential for wood checking, twisting, and deteriorating.

The post details weren’t the only challenges we saw in the plans. The architect’s design took elements from the house and incorporated them into the fence. The broad, multilayered belly band on the house inspired the entablature along the top of the fence, and the repeated-column motif became the posts with plinths and caps. These details clearly tied the fence to the house, but on a freestanding structure exposed to the weather, they would be difficult to accomplish.

Mark is a finish carpenter and furniture maker, so he took on the challenge of designing the wood parts that would make up the entablature. My job was to create a structure capable of supporting these furniture-grade details: an assembly of steel posts and stainless-steel mesh through which climbing plants could grow.

Steel has a long life

A few years ago, I started using 1 ⁄8-in.-thick 2×2 steel tubing instead of pressure-treated wood posts for all my fences. I’ve seen so many wood posts that check, twist, and bow over time that I knew there had to be a better way to build a fence. Steel prices have gone up in the intervening years but not enough to stop me from using it.

With just a few adjustments in the installation process, I have found steel to be an almost-perfect fence-post material. Steel has great longevity, strength, and ease of installation. There are a few steel-tubing suppliers in my area, so I chose the one that was closest to the job and that would cut the steel to the rough lengths I needed. At the time, the steel cost about $2 per ft.

Stainless-steel mesh for between the posts is not as widely available. I searched online to find a mesh that ivy could grow into and that would provide some privacy. Once I found what I wanted (www.thewesterngroup.com), I followed the manufacturer’s link to a local supplier. This steel mesh cost $700 for a 6-ft. by 8-ft. panel of 3 ⁄16-in. wire on a 2-in. grid. I could have spent less by choosing regular steel over stainless and having it powder-coated with the steel posts.

Using steel requires planning

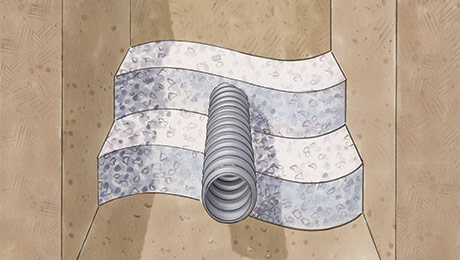

One crucial point in my plan is that the steel-to-wood and steel-to-steel connections need to be well thought out. Mark assured me that he could attach the faces of the posts and the entablature with self-tapping screws. However, making the post-to-mesh connection was a multi-step process. First, we brought the posts to a shop where 1 1⁄2-in. flanges were welded on everywhere we needed to attach the mesh. Every flange had a matching flange that was left loose. Both the flange and its match had been drilled with 1⁄4-in.- dia. holes every 16 in.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below: