Hue and Cry

Great moments in building history: What exactly is 'stone color'?

I used to have a small painting business, and when I was starting out, I occasionally ended up with some jobs my more experienced competitors knew enough to avoid. The worst of these jobs started with the town stockbroker’s ancient chicken house. I took on the job at a ludicrously low price, and eventually, my crew and I created a veritable chicken palace, gleaming shiny red and white in the hot Pennsylvania sun.

The stockbroker was so pleased with the results (and especially the price) that he asked me to touch up his garage while I was there. As I was doing the garage, the stockbroker, on the alert for another good deal, suggested that his barn would benefit from our attention so that all his outbuildings would be equally pristine. I, on the other hand, was on the alert for how I might be in for another bad deal, so I put in a much more substantial (and realistic) bid after looking over the barn carefully. After a bit of hemming and hawing, the deal was set.

Then came the matter of color. The old stone barn had been stuccoed over and was a flaking, dirty white. I presumed that it was to remain white, but the stockbroker said he wanted “stone color.” “You mean like gray,” I suggested. “No, no, I want stone color. Stone color! Natural stone color,” he said, waving his hands and speaking loudly as people do when they are communicating with someone who is particularly obtuse.

We were at an impasse until I looked behind him and saw his house, an impressive Pennsylvania fieldstone colonial. “Oh, you mean like your house?” I said. He turned around, following my gaze, and took in his house, as if for the first time. “Yes, yes, that’s right—natural stone,” he said, walking off to his back door, satisfied to have resolved this minor technical issue.

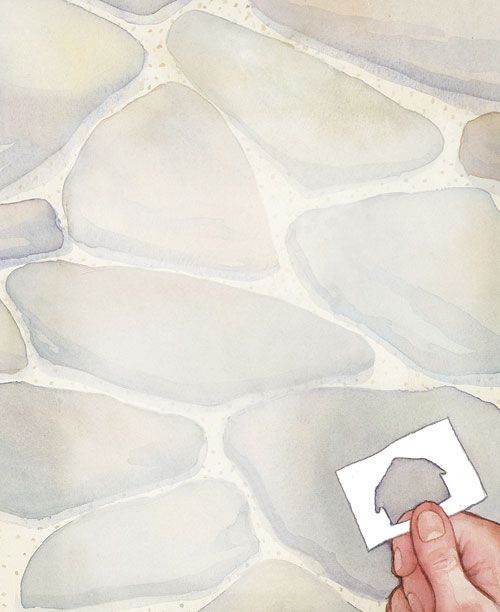

I followed behind to inspect the house at closer hand, and coming to the door, I examined the stones. I had never looked at stonework closely before, and I was surprised to discover that all the stones were different colors. I motioned the owner over and pointed out this fact, which appeared to be news to him as well. He seemed to take less interest than I did, although he agreed with me that I could pick one of these stones to match. I suggested at random one about eye height next to his door. “Fine, fine,” he said, dismissing me with a wave.

My color chips contained nothing close, so I returned the next morning with tints and base. A little experimentation showed that red and brown was close, but not quite. Some black to dull it down, and then a little blue. I let it dry, and it was dead on. I called out the stockbroker and showed him my sample, about 3 in. sq. on a white card. He glanced at it briefly and agreed that it did seem to match the target stone, and by the way, he was leaving for vacation with his family shortly and would that be a good time for me to commence work? It was.

When time came to start, I was at the paint store getting supplies and griping to the manager about all the work it would be to mix the color for two coats. Always trying to help out the new guy, the manager pointed out that because the first coat wouldn’t show, I didn’t need to use finish color for that. As a matter of fact, he had a number of cans of returned mismatched exterior latex that he could sell for a low price. Of course, they were single gallons, all in different colors. I thought for a minute. Because the homeowner was away, he wouldn’t know what color the base coat was.

So we walked out of the store with gallons of the most hideous orange, green, blue and yellow. We gave the barn a base coat of wild vertical stripes. Well satisfied with the work, I then undertook to mix the finish color in quantity, which wasn’t hard because I’d kept track of the proportions from the test. Somehow, though, in 5-gal. batches, despite matching the target stone, the color looked different. Red and blue were making—purple! There was no getting around it: Although Pennsylvania fieldstones seem reddish brown, they have a distinct purple tinge—a pastel, brownish shade, but purple nonetheless. Because each stone is a slightly different hue, the overall effect is disguised in a wall.

My partners and I made a few more test samples. They matched perfectly. What to do? Well, the stockbroker had wanted natural stone color, been insistent about it, actually. This color did in fact match the natural stone. So we set about spraying over our beautiful stripes with the purple mix.

Then the stockbroker came back from vacation—early. We were still at work. He saw half his beautiful barn with psychedelic stripes and the other the color of natural stone. All he said was, “Purple! You’ve painted my barn purple!” It was all he could repeat for some time, his face assuming a similar tinge.

After he’d exhausted himself, we took him back to his house to show him the color sample he had approved. In a fit of rationality, he acknowledged that we had painted his barn the color of his stone house, or the one stone, anyway.

A purple barn was not what he wanted. But we weren’t about to repaint the barn for nothing. When I presented an estimate for repainting, though, the stockbroker decided that maybe the natural stone color wasn’t so bad after all.

—Robert S. Porter, Chadds Ford, PA

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Handy Heat Gun

Reliable Crimp Connectors