Hut, Sweet Hut

Great moments in building history: Always remember the importance of community

Working on a U. S. Public Health Service research grant, my wife, Janet, and I spent 15 months on Tanna, a small Melanesian island in Vanuatu (formerly the New Hebrides). Our goal was to contact and to live among the native people of Tanna, who inhabited a jungle area about 10k from any signs of Western civilization.

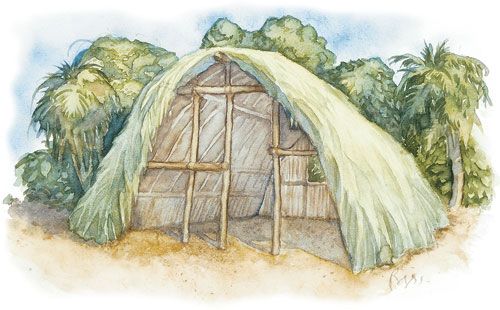

We negotiated with the Tannese for a place to live and were offered a “white man’s hut” with square sides, tarred-and-sealed tin roof and wild-cane beds; this style of house was advocated by Western missionaries to Tanna. The missionaries, however, didn’t realize that the traditional Tannese hut had slanted walls, which are more effective at deflecting wind than the vertical walls of the white man’s hut. Also, the cracks in the wild-cane-stalk walls of our hut didn’t permit much privacy. The beds were as uncomfortable as concrete floors. And the leaky, weak tin roof absorbed lots of daytime heat and released the heat at night. Even though we were living in the South Seas, we were at an elevation of 400m, high enough for cold evenings.

One day while we were discussing original customs with Yelman, our chief contact with the Tannese, we talked about the advantages of traditional huts, or kwankanip, vs. white man’s huts. A few days later, Yelman stuck a pole in the ground about 10m from our hut to announce a limtetian; the pole was a symbol to nearby residents and visitors that he proposed to build a traditional hut for us and with us on that spot.

House building on Tanna is at least as complicated as Western projects, which have their dealings with architects, builders, bankers and others. Yelman negotiated to gain approval, support, resources, physical labor and commitments of time. To repay those who agreed to help build our new home, we agreed to provide Western medicines under close supervision from the physician at the hospital 10k away. For instance, one man whose three children received scabies treatment worked with the vines for the hut. Yelman insisted that barter, trade, exchanges and gifts were an integral part of tradition. We had an opportunity to learn the art of negotiation, the values of many materials and the locations of resources.

Several weeks went by with almost daily negotiations. Yelman rarely missed a chance to bargain for strategic resources. Then, in a carefully arranged sequence reflecting construction requirements and social and political protocols, we helped Yelman cut a large number of poles of wood from a piece of donated property. Next, we collected many long and some short vines from an area along a steep ravine, and wild cane from several clumps near our hut. When our supply of wild cane ran out, we negotiated to get more from distant clumps.

Each piece of our future hut had to be prepared. The vines, for example, had to be coiled, left to dry for a day or two, heat-treated, re-coiled, soaked and stripped of bark. Then Yelman and various helpers began clearing a space, digging in poles, bringing in and raising a center beam from a banyan root, and creating a framework. The crew used no nails, hammer or Western tools—except for an ever-present machete—even though such materials were available at the trading post near the government outpost and the British hospital about 10k away.

After the frame was ready, we waited for a week or so. Then a group of about 15 women and children cut down coconut fronds and wove them into roofing material. To allow work to continue smoothly, several women used their time to cook sufficient taro, yams and other foods to sustain the many others who devoted their free time to the roof.

After the roof was complete, finishing touches such as reinforcing the bottoms of the wild-cane walls were put in place, and we quickly saw the advantages of the traditional hut. The hut, squat like a quonset hut, was virtually impervious to rain and wind. The vines assured that a tin roof wouldn’t come crashing down on our heads, even in vigorous earthquakes. By living close to the ground, we could build a very small fire in the hut, and the smoke would rise, killing or driving away the little bugs and beetles that were constantly feasting on our walls, clothing, paper and skin. Best of all, the hut was designed for sleeping, not sitting. We gained an appreciation for the close relationship the Tannese had with the outdoors. Even in rain, their usual habitat was outside, not inside.

The test of the hut’s durability came when a cyclone veered close. The storm’s peak winds did not hit Tanna, but the ones that buffeted us were severe. When a crack of thunder rolled across the jungle, we dashed out of the white man’s hut and into our traditional hut, where we remained safe and dry, without worries about the storm.

After our hut was completed, everyone in the community felt a sense of ownership because most people in the vicinity had contributed to its construction. Our Tannese hut was a welcome exchange for our investment in treatment for scabies, malaria, dengue fever and disease prevention. I recollected an old-fashioned barn-raising of my youth, when our neighbors helped my dad and me finish a big dairy barn on our New York state farm. Like the barn-raising, the building of our Tannese hut reminded me of the importance of community.

—Robert J. Gregory, Palmerston North, New Zealand

Drawing by: Jackie Rogers

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Handy Heat Gun

Reliable Crimp Connectors

Affordable IR Camera