The Ming Vase

Great moments in building history: You don't break the Ming vase

Years ago, when I started my first company, I used to tell my employees, “There are three things you don’t do: You don’t start fires, you don’t cause floods, and you don’t break the Ming vase.” Vase, by the way, is pronounced väz in this case. As my father always said, “A va¯s costs less than 50 bucks.”

A few years ago, I had a business with a couple of partners. One of our projects was the renovation of a spacious apartment at Central Park West and 70th Street in New York City. My partner had retained the services of a loud, obnoxious plumber. My partner was trying to be competitive when he included the plumber’s price in our bid. However, if the plumber had done the job for free, it still would have been a lousy deal.

The plumber used to sit on a sawhorse in the middle of the job site and tell the carpenters, the marble setters, the electricians, the air-conditioning crew and even his young plumbing assistant how to do their jobs. He referred to the architect’s specifications as the “jokebook.” I had my hands full.

As part of the kitchen renovation on this job, a new layout required that we relocate the gas line for the stove from one side of the room to the other. Because the building’s management would not let us chop a channel in the concrete floor, the best route was to go through two walls to get the gas line around to the new stove location. One of the walls was a party wall. (A party wall separates two adjacent apartments in the same building.)

This was a building that had been built between the World Wars, and the partitions were made from hollow terracotta block, which was standard practice in those days. Party walls are usually—but not always—constructed from two separate partitions with an insulated airspace between.

Because I was familiar with the plumber’s extraordinary personality, I took him into the kitchen and carefully outlined my concerns regarding the chopping of an 8-ft. long channel into this party wall. The plumber assured me with much confidence and aplomb that my concerns were unfounded and without merit. I had my doubts, but I knew that he had insurance, so I went on with my other tasks.

I came back to the kitchen a half-hour later to inspect the progress. As I surveyed the newly chopped channel from the far side of the room, my eye caught a small, unusual dark spot in the otherwise dusty orange of the terracotta. I went over to investigate, and leaning down, I picked a piece of broken terracotta from the channel that had green plaster on one side. The kitchen we were working on was painted yellow.

My heart raced. I knelt down and peered through a hole into the next apartment. It was dark, like the inside of a closet.

I got up, went into the service hall, which serviced both apartments, and knocked on the neighbor’s door. I explained that there had been a slight mishap and that my plumber had broken a small hole through the wall into her closet. The owner blanched and said that there was no closet there, only the built-in pantry cabinet that held the collection of antique china. I blanched.

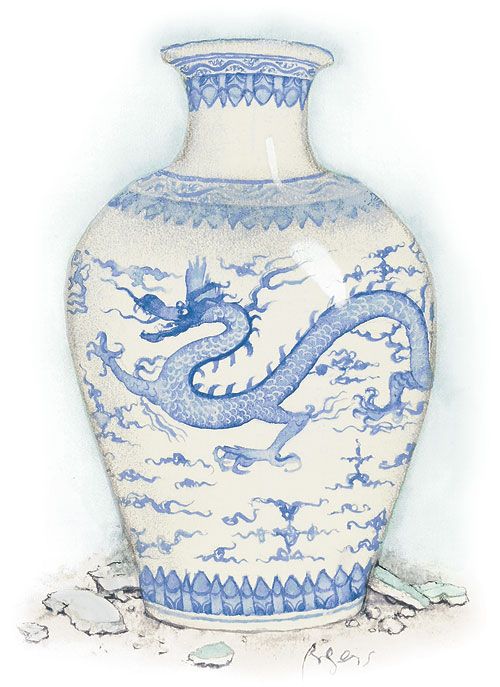

We opened the doors to the cabinet and peered inside. The cabinet had been built against the plaster wall with no wooden back. What we saw was a beautiful set of hand-painted antique bone china, service for 12, stacked within. The contents were covered in dust and bits of plaster, and in the middle of it all stood the Ming vase.

Miraculously, there was no damage to the china or the vase. The neighbor, who was a bit nervous about the whole event, had her china and vase washed, and we patched and painted the hole.

As I have since lectured ad nauseam, “There are three things you don’t do: You don’t start fires, you don’t cause floods, and you don’t break the Ming vase.”

—Louie Meader, Cherry Valley, New York

Drawing by: Jackie Rogers

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Handy Heat Gun

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Reliable Crimp Connectors