Exploiting the Elements of Passive Design

This home uses five systems to reduce its environmental impact, lower its operating cost, and improve its connection to the land.

Magazine extra: Listen to James explain the hallmarks of Pacific Northwest-style architecture and view additional photos of this project, as well as the work of two of his design heroes, Peter Bohlin and James Cutler.

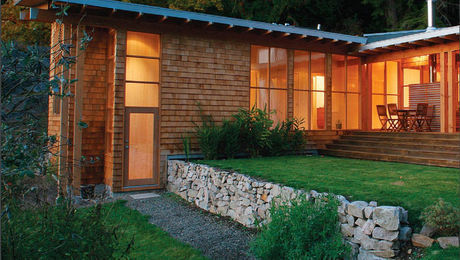

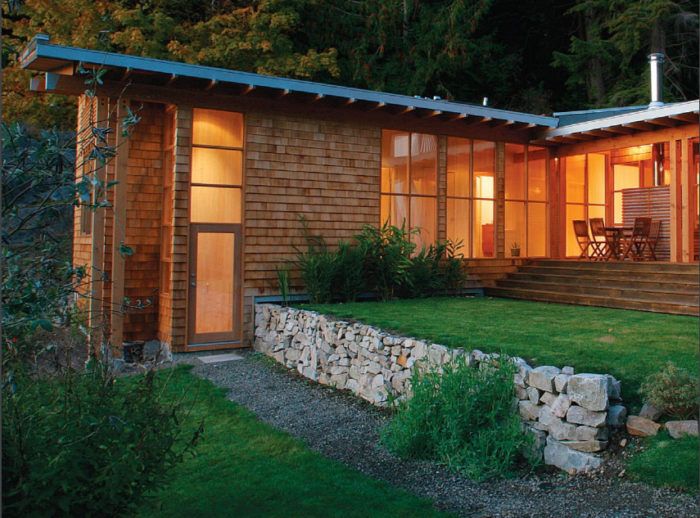

Every site has a story to tell, and the right house can help to tell that story. Located on the western coast of Bowen Island in British Columbia, this house is a good example. My clients, a professor of East Asian archaeology and a researcher from Kyoto, Japan, had worked the land for years, cultivating extensive gardens of ornamental plants from around the world. When they approached me to design a house for the property, they had only two requests: The home must fit the site, and it should have minimal impact on the landscape. The rest of the design was left in my hands. As a graduate of the University of Oregon, I have had a lot of training in passive design. It was only natural, then, to design around passive environmental systems that would use the natural elements of the site to improve the overall look, comfort, and performance of the house.

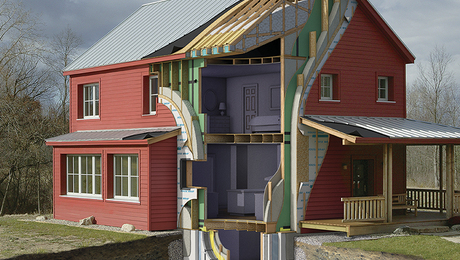

Passive environmental systems are a basic part of good home design

Passive systems harness natural elements—rain, wind, sunlight, soil—for the benefit of the house. They shouldn’t be confused with active systems, such as photovoltaic cells or ground-source heat pumps. A properly designed house uses more than one passive system, and it relies on the relationships between each system to enhance the building’s overall performance. The passive systems that I integrated into this house were based both on the general needs of the homeowners and on the specific demands of a challenging site.

A unique lot provided natural design opportunities

On my first visit, I realized quickly that the property posed a unique set of design challenges. Not only did the building site face west, but it also was surrounded by forested hills and granite rock outcroppings to the south, east, and west that captured the warmth of the sun throughout the afternoon. Large stands of Douglas fir protected the site from the ocean breezes that typically cool island homes. The resulting microclimate is more like southern Oregon than southern British Columbia, which is known for its temperate summers. Developing a way to cool the house was as important as determining how to heat it.

The site’s other major feature—a large, mature garden—demanded an intensive supply of water from an already-taxed well linked to several surrounding homes. Proper irrigation was a priority.

With these major challenges in mind, I integrated design details that would handle heating and cooling demands passively, the need for water conservation and rainwater harvesting, solar-shading, and natural daylighting.

For more photos and information on how to use simple exposed materials, click the View PDF button below.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Code Check 10th Edition: An Illustrated Guide to Building a Safe House

The New Carbon Architecture: Building to Cool the Climate

All New Kitchen Ideas that Work