Fire Sprinklers

With a smoking record for saving lives and protecting houses, it’s no surprise sprinklers were adopted into the International Residential Code.

Synopsis: Fire sprinklers are usually thought of in retail and office contexts. However, their proven life- and property-saving abilities led to their inclusion in the International Residential Code, effective in 2011. In this article, associate editor Chris Ermides looks at the positive impact of residential fire sprinkler systems in communities where they’ve been mandated. He also examines the way fire sprinkler heads work, the two options for sprinkler systems (one integrated with the house’s plumbing and one strictly dedicated to putting out fires), and the cost of a fire sprinkler system as part of the construction of a new home (a little less than 2% of the overall construction cost).

Sound off about this code change in the FineHomebuilding.com blogs. Read more…

While photographing an article with an electrician a couple of years ago, I got a tour of his new home. It was well built and, of course, had a vast array of high-tech gadgets. But what caught my attention most was the set of valves and gauges that shot from the home’s main water supply line. “Is that for your radiant-floor heat?” I asked, pointing to the pressure gauge, the backflow switch, and a couple of shutoffs. He grinned and said, “Sprinkler system.” He’s a man of few words, but he’s also a full-time firefighter. I knew that he wasn’t talking about sprinklers that water the lawn.

He then told me that smoke alarms reduce the risk of dying in a fire by only 50%. Smoke alarms and fire sprinklers combined, however, lower the risk by 82%. Given those numbers, adding 1.5% to the construction cost of his home felt like a worthy investment.

Apparently, a lot of other people think so, too, because the International Code Council, the governing body responsible for the International Residential Code (IRC), approved a proposal to require fire sprinklers in all new homes. The requirement appeared in the 2009 IRC and took effect on Jan. 1, 2011.

Sprinklers save lives and houses

According to the U.S. Fire Administration, a house fire starts about every 80 seconds in this country. In the 414,000 fires that occurred in 2007, nearly 3000 people lost their lives, and 14,000 were injured. Besides the casualties, $7.5 billion went up in flames.

In Scottsdale, Ariz., home fire sprinklers have been mandatory since 1986. More than 50% of the houses there (about 41,000) are now protected by sprinklers. According to a 20-year study known as the Scottsdale Report, the Rural/Metro Fire Department found that of the 598 house fires that occurred, there were no fatalities in the 49 homes equipped with fire sprinklers. In the houses that weren’t protected, 13 people died. The average fire loss in homes with sprinklers was $2166, compared with $45,019 in homes without them.

States including Illinois, Maryland, and Oregon have also had residential fire-sprinkler codes on the books for years. Whether municipalities are going to adopt the new rule is still unclear, and very much up for debate. The National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) is working to convince states that they should block municipalities from adopting the new code; so far, 10 states have legislation in the works to do just that. The NAHB fears the added cost of sprinklers will deter people from building a home.

“Local adoptions have been growing around the country, including areas served by volunteer fire departments,” says Darren Palmieri, product manager for Tyco Fire Suppression and Building Products. Sprinkler systems can lessen the strain on municipal fire protection services, which can help in areas with dwindling volunteer rates.

Although sprinkler systems aren’t meant to replace firefighters, their purpose is to save lives. Most fire-related deaths in a house happen within five to 10 minutes of ignition. This critical point is called flashover when all combustible materials within a room simultaneously ignite. No one survives flashover. Sprinklers control the fire enough to delay flashover. They buy time for the home’s occupants and for the fire department.

Pinpoint protection only when you need it

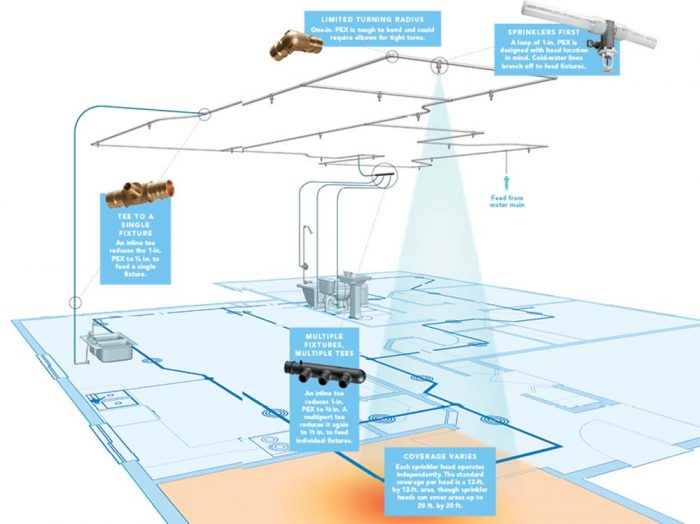

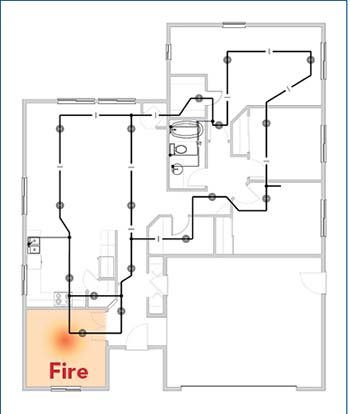

A sprinkler system is composed of a series of heads tied into a network of piping fed by the home’s water system. The standard coverage per head is a 12-ft. by 12-ft. area, though most sprinkler heads are listed to cover areas up to 20 ft. by 20 ft. The head closest to the fire will activate once it detects a temperature of 155°F. According to a study referenced on Homefiresprinkler.org, in about 90% of homes, only one sprinkler is necessary to control a fire.

Fire-sprinkler systems are extremely reliable, and the technology is fully developed, according to Julius Ballanco, president of the American Society of Plumbing Engineers. But even though the systems have a proven track record, some misconceptions remain. One of the most common is that a sprinkler head can activate accidentally. However, statistics show that only one in 16 million heads discharges falsely. Because sprinklers are heat-activated, some consumers remain wary of high air temperatures that might naturally exist at the ceiling. “In some areas of the home, like laundry rooms and near stoves, temperatures can run high up at the ceiling,” Palmieri says. “In these cases, sprinklers rated to activate at a higher temperature should be used.”

The other common misconception is that water damage is significant. Again, that’s a poorly founded notion. The Home Fire Safety Institute says that a fire hose disperses an average of 2935 gal. to control a fire, whereas a sprinkler system dumps only 341 gal.

There are two options

The National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 13D is the standard for the installation of sprinkler systems in one- and two-family homes. It requires sprinklers in living areas only, not in smaller bathrooms or closets, nor in pantries, garages, attics, or other concealed nonliving spaces. The system’s piping must be charged with water at all times and can be configured in one of two ways: as a stand-alone or as a multipurpose system.

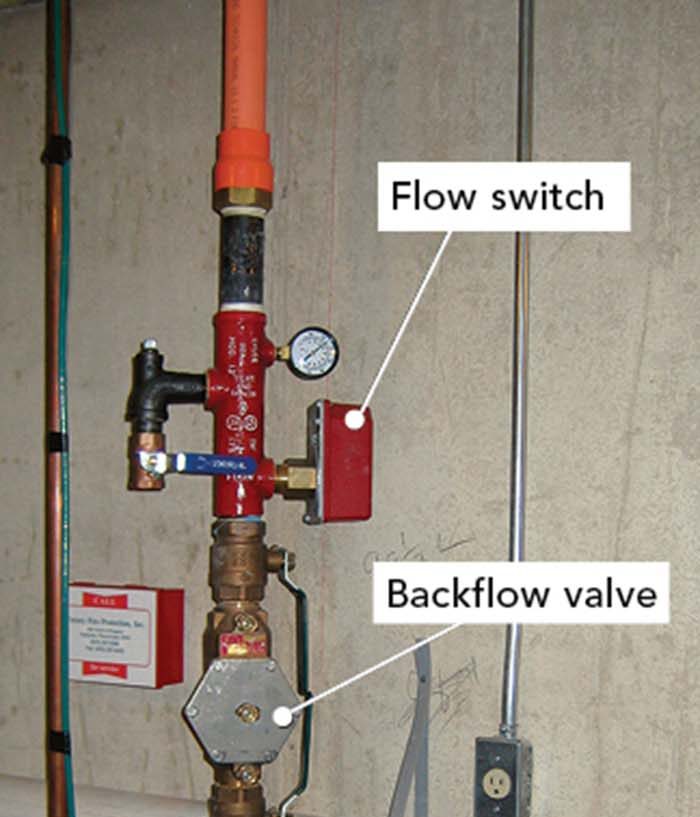

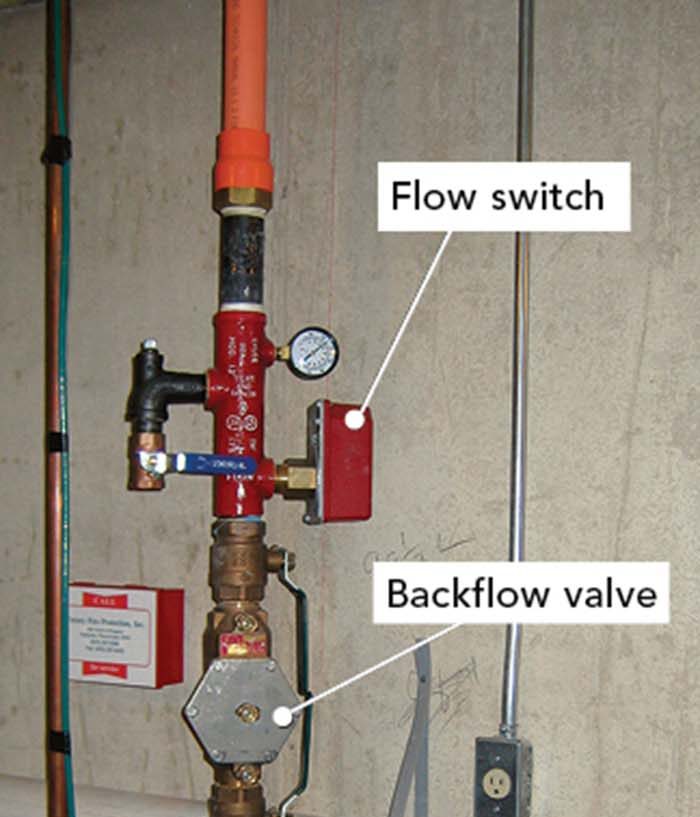

In a stand-alone system, the piping is separate from the rest of the house’s plumbing. Water in these systems is stagnant, so depending on the type of piping used and the local requirements, a backflow valve may be required. Some local codes also require a flow alarm, a device that sounds by sensing the flow of water when a sprinkler head discharges. The alternative—a multipurpose system—is tied into the home’s plumbing system and shares cold-water distribution lines. This type of system does not require backflow prevention.

Stand-alone systems typically must be installed by a certified sprinkler fitter. Dominick G. Kasmauskas, regional manager for the National Fire Sprinkler Association in New York, says some states require that multipurpose systems be installed by a licensed sprinkler contractor.

Houses that aren’t connected to a public water supply can be protected as well. The downside, of course, is the higher cost. Sprinkler systems fed by a well require a holding tank and/or a pump strong enough to keep the system running should a sprinkler head activate. The NFPA 13D standard requires that there be enough water available to discharge 20 to 26 gal. per minute (GPM) for 10 minutes.

Check, please

The installation cost for sprinkler systems is what scares people most. According to the Fire Research Foundation, the national average is about 1.61% of overall construction cost, about $1.52 per sq. ft., but as high as $3.50 per sq. ft. or as low as 85¢ per sq. ft. As residential sprinkler systems become more common, it is likely that prices will become more competitive.

There is some disagreement about which system is less expensive. Stephen Ziamandanis, a representative for Uponor (www.uponor-usa.com) and a certification instructor, contends that multipurpose systems are far less expensive. “You’re using the same piping for your cold-water plumbing lines, which saves on material cost, ” he says, “and you’re saving labor costs because one contractor—a plumber—is installing one system.”

Stand-alone systems can’t be installed by a plumber unless he or she is also a certified sprinkler fitter, so there’s another contractor to contend with. New sizing and installation guidelines added to the NFPA 13D and the IRC now allow the installing contractor to design either a stand-alone or a multipurpose piping system.

Tyco has been conducting its own studies to determine if there’s a cost difference between the systems. According to Palmieri, current findings suggest the two are about even. “The material cost is less expensive than multipurpose, which balances out with the extra labor costs,” he says. Julius Ballanco agrees: “It seems to be about a wash.”

The most volatile cost these days is the tap cost, levied on any house connected to a municipal water system. A standard tap fee is about $50, depending on the area. Adding a sprinkler system will likely require a larger line (3⁄4 in. to 1 in.), which can run as high as $2000. Some areas are trying to charge a standby fee as well. Several states are getting involved to regulate tap fees and block standby fees.

When amortized over the course of a 30-year mortgage, the cost of a fire sprinkler system isn’t a financial burden for most people. Insurance companies often offer a discounted rate on homeowner’s policies that can range from 5% to 15% if the house has sprinkler protection. The savings might not be significant, but a sprinkler system isn’t the type of expense that can be calculated for a monetary return on investment. The investment is in a priceless commodity: life.

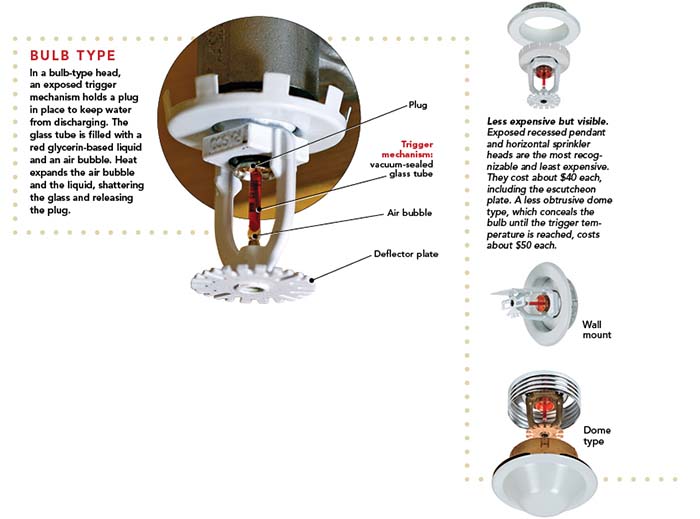

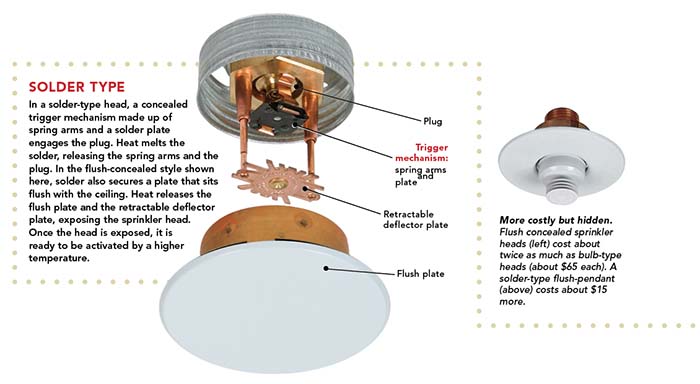

Sprinkler heads are heat-activated

Wall- or ceiling-mounted sprinkler heads are connected to a network of piping. Each head functions independently, so only the head(s) closest to the fire will activate. The heads all have a plug held in place by a bulb-type or solder-type heat-sensitive trigger mechanism. Once the mechanism reaches its activation temperature, it releases the plug and the water. Water then sprays over the deflector plate, which disperses it evenly around the room.

Standard sprinkler heads are set to activate at 155°F. Because they’re heat-sensitive, they should never be painted or covered. Most manufacturers can color-match and offer a variety of styles. The examples are shown here illustrate the most common styles.

Option 1: Fire protection and plumbing in one

Option 1: Fire protection and plumbing in one

A multipurpose system is integrated with the house’s plumbing, unlike a stand-alone system, which is separate (p. 46). One pipe loop with sprinklers is run off the main water line, and cold-water lines branch off to feed the kitchen and the bathroom. Combined plumbing and sprinkler systems can be piped using PEX (example shown here), CPVC, or copper; the pipe must be NSF- and UL-approved. Manufacturers typically engineer their systems for each project and train the installers, who are often plumbers. Any future remodeling work that affects plumbing could require additional engineering.

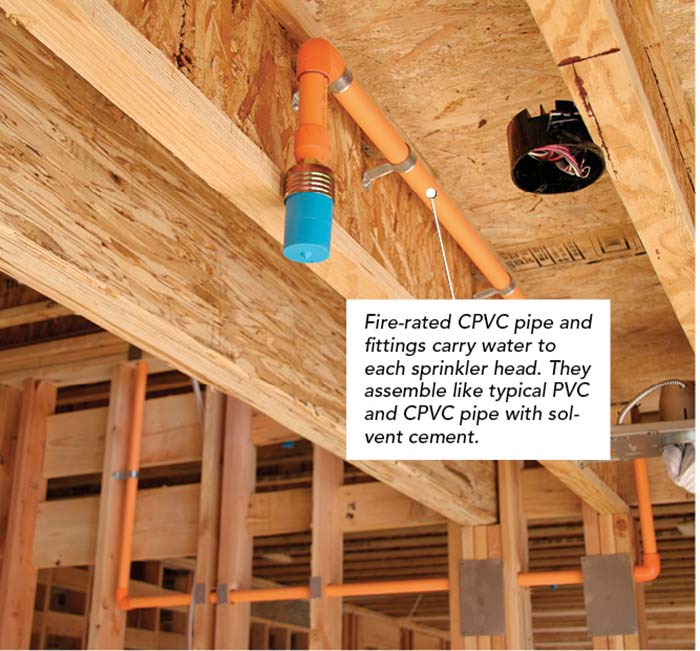

Option 2: A system dedicated to dousing fires

Option 2: A system dedicated to dousing fires

A stand-alone system is composed of a separate set of CPVC or copper pipes and fittings dedicated just to the sprinklers; water does not mix with the home’s plumbing. The system is fed from a riser that tees off the home’s main water line. Because the water in the stand-alone system is stagnant, a backflow valve might be required to ensure that it does not contaminate the home’s water lines. A gauge monitors the pressure, while a flow switch alerts the home’s occupants when water is moving through the sprinkler system. In most states, a stand-alone system can be installed only by a licensed sprinkler installer. Manufacturers suggest testing the system annually to make sure all valves and switches are working properly. Because this system is separate from the home’s plumbing, future remodeling work won’t affect the sprinkler setup.

From Fine Homebuilding #206

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.