This is a continuation of my first blog on piece workers who changed the way all of us build. When I first started writing for Fine Homebuilding magazine in 1988, I told them that I was not a “fine homebuilder.” I didn’t know how to build double-helix stairs for example. The editors there told me that “good construction methods can be used by anyone whether they are building tract homes or mansions.” I liked that answer.

I recall some legendary piece workers from those days in the 1950s. These carpenters were even better than the best at doing their part in building a house. Before a usable 8d nailgun came around, in the 1960s, all nailing was done by hand. So incredible nailers were born. One was a floor nailer named Arturo with a nickname of “The Lizard” because of the way he moved when nailing.

Pre-nailgun methods for nailing off roofs and floors

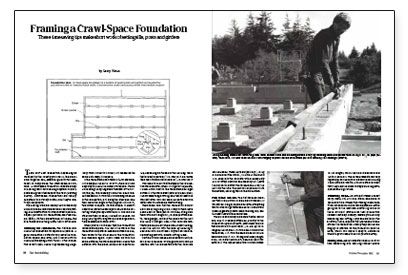

He introduced us to the nail-buggy and the nailing-sled. These were simple home made tools that made it easier to nail off a floor or roof. The nail-buggy is built with a 16 in. square piece of plywood. Four screw-on casters with wheels at least three inches in diameter are attached to this seat. For years we sheathed floors and roofs with 1x6s on the diagonal. This material was often utility grade so the larger wheels allowed you to go over the bad spots. The nailer sat on the seat of this buggy, pushed himself backward along a joist nailing between his legs as he went. When he got to a wall or edge, he turned around and nailed back the other way.

Well, Arturo was a master nailer on his buggy. At night he would take home a keg of 8d nails. (Nails in those days came in 100 pound wooden containers shaped like a beer keg). He would bundle the floor nails in packets of 25 or 30, heads all facing in one direction, and wrap a rubber band around them. His job site buggy had a bread pan attached to the side. He would place his nail packages in it and start nailing, reaching down whenever he needed more nails. Each nail was fed out of his left hand one at a time (Very Efficient Carpenter [VEC], p 62, by Larry Haun), tapped to set, and then driven home—one lick! All of us could do nearly the same, but he was a lot faster. How I wish I had a video of him nailing off a subfloor!

The roof sled was similar in that it allowed you to nail strip sheathing to rafters while sitting down. It too was a piece of ¾ in. plywood covered on one side with tin from the sheet metal guys. The tin at the front was rounded over one end and there was a hole at the back so you could pick it up. We sat on these at the ridge and nailed off two rafters, 16 in. o.c., as we slid down toward the eaves.

Door-hanging before pre-hung doors

The three Schaeffer brothers were legendary door hangers (FHB 53, p 38-42). I knew Al the best. Each one of them, working with a helper, could hang up to 80 doors or more a day in the tracts. Al would go through the house with his 6 ft. hinge template, hold it in place on a jamb with his foot, and use a router to ready the jamb to receive two or three hinges. His helper then carted the doors around, holding them in the openings with a homemade door lift and device to hold the door snug against the jamb (FHB 165, p 68-71), and scribe them to fit. He then brought the door to Al’s well-crafted bench where it was sized with a planer and routed for hinges. There was a mark on his bench that told him where to drill holes for the lock rather than measure the height. The hinges were secured to the door with screws. The door was then carried by the helper to the opening where the hinges were screwed to the jamb. Almost always the fit was perfect.

[[[PAGE]]]

The ordinary bright-shiny nails were ripe for conversion because they are not easy to drive with one lick. We eliminated all common nails and built with 8d and 16d box nails. Then the gas-wax process for nails arrived on the scene. We would buy nails by the pallet load, take them to the shop, open and treat them with a solution of wax that had melted in gas. It’s an easy, simple process that is no longer politically correct. Set a 5 gal. bucket of gas in the sun, drop in a bar of paraffin, and let it melt. Pour a cup this solution over the nails, shake the box, let the gas evaporate and you have a wax coated nail. These nails were forerunners of the vinyl coated framing nail.

Waxed nails, of course, drive through wood like a hot knife through butter. Their holding power, once they were driven, was about the same as a shiny nail. The dried wax seemed to cling to the wood making it harder to pull.

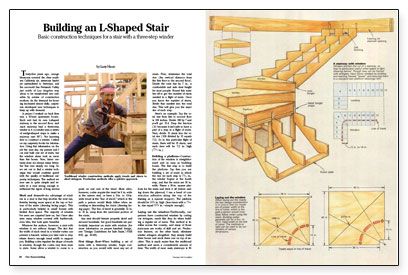

Elmer Griggs was well known as a master roof cutter. His nickname was Moe. In days past we used to lay out common rafters with a framing square and make plumb cuts at each end for the ridge and eave cut and for the bird’s mouth cut at the plate line. This rafter was then used as a pattern for the rest of the rafters. It could take days to cut all the rafters.

Moe used specialty tools to cut this kind of roof in an hour or so. Stock was laid out on long, low horses with the crown down (FHB 60, p. 83-87). Three lines were snapped, one for the ridge, one for the seat cut, and another for the tail cut. He used a worm-drive Skil with a dado head to cut the seat cut with one pass. The ridge and tail cut were done with a blade large enough to cut edgewise through a 2×4 or 2×6. OSHA would have found these tools a bit scary because at that time guards were often not adequate. It meant that you had to pay attention to what you were doing. Not bad advice whenever you are working with any power tool, no?

Later on we all used a swing table, first a homemade one and later a manufactured one, on the Skil saw (See FHB 177, p 101). This allowed us to lay the saw over to more than 45 degrees to cut the plumb and level cut of the seat cut.

Measure never, cut once

I imagine that everyone has heard the old saying when working with wood: “Measure twice, cut once.” But we learned early on not to measure at all. Much frame work can be done quite accurately by “eyeballing” where a cut should be (VEC, p 76). Further, cutting square without a square in frame carpentry is quite easy with just a little practice. No need to pull out your carpenter’s pencil and speed-square, mark a square line, and return them to your nail bag. Just cut! Line the front end of the saw table up parallel with the edge of a 2x and make the cut (VEC, p 37). It really is that simple.

We learned to cut cripples and blocks not one at a time, but a hundred all at once (FHB 88, p 58-61). Rake walls were chalklined on the floor (VEC, p 104) making them easy and fast for anyone to build. Every trade had to look at how they did their work. Water laden plaster that soaked houses gave way to drywall. Plumbers put away their smoking pots of melted lead and began working with flexible pipes that were easy to join. Electricians changed from a rigid to a flexible conduit and then to romex cable that could be installed in a fraction of the time. Tin benders laid aside their soldering tools and traded metal ducts for flexible ones that no longer had to be wrapped with asbestos tape.

And so it went, on and on, until every aspect of the constructing a building was looked at, scrutinized, challenged, streamlined, and simplified. The end result was a house built rapidly and one the ordinary worker could afford probably for the first and last time in our history. The median cost for a two or three bedroom house was under $10,000. What we left behind was not quality. We left behind the gingerbread and craft finish work you see in other types of houses. These tract homes we built may not fit your taste. They are not mega-mansions, but they are well built. And now, fifty or sixty years later, they are still standing!

Larry Haun

August, 2010

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Affordable IR Camera

Handy Heat Gun

View Comments

Great memories, with thanks, Larry. My grandfather framed in the 1930s -- 1950s and claimed to have built "near every damn house in town." I have his framing square and the head to his 16 oz hammer.

The framing square, for some reason -- maybe a defect in manufacturing -- isn't square! But as you say he probably didn't use it anyway -- I've looked at the roofs of "near every damn house in town" and they came out just fine.

Your story recalls his face. Thanks for that, too.

Well we are two degrees apart.

Elmer taught roof framing at the Ventura District Council on Dawson Dr. in Camarillo to the apprentices. I took that class. Never heard the "Moe" nick name but I think we called him "Elmo" derisively.

I never stacked behind Elmer but he was a foreman on two jobs that I rolled trusses and cut and stacked the sheds over the living rooms. Can't remember the name of the framing contractor. It was in Thousand Oaks and Westlake.

I got to know one of his sons, he lived near Channel Islands Harbor and I lived near by. I remember he had a collection of insects, mostly beetles and he ice skated.

There were a ton of charactors at the time. No shortage in the earlier days I'm sure.

Every once in a while I would work in the Valley or Simi Valley.

Thanks!